Preparing for Retirement

Top Findings from a Survey of Public Workers on Retirement Benefits

OVERVIEW

For the past several years, policymakers across the country have been taking a close look at state and local retirement systems. Since 2009, 48 states have enacted retirement plan changes, with some states enacting multiple reforms,1 in an effort to make pension plans more fiscally sustainable.

The recent and widespread adjustments to the public-sector pension systems have increased the need to know more about state and local workers’ retirement preferences; in addition to increasing pension solvency and helping employees achieve a secure retirement, policymakers should aim to recruit and retain a talented public-sector workforce. While many national surveys have looked at retirement-related issues, few have focused specifically on state and local public-sector workers.

The Pew Charitable Trusts hired the national market research firm SSRS to survey public workers on retirement plan design, retirement knowledge, and retirement confidence. The survey used a random, nationally representative sample of 2,110 state and local full-time government workers from every state and the District of Columbia. The respondents were public workers from across the professional spectrum. They were employed in education, public safety, or general government administration and included social workers, nurses, doctors, engineers, lawyers, and those in the skilled trades.

In all, more than half—53 percent—were teachers or other education workers. Twenty-five percent were local noneducation workers, and the remainder were state noneducation workers.2

Key findings

More than two-thirds of state and local public workers expressed confidence that they would have enough money to live comfortably in retirement—a substantially larger proportion than those surveyed recently in a separate study of the U.S. workforce as a whole.

The public employees also said that they place high importance on their retirement and pension plans but they rank job security, work-family balance, and health care above retirement benefits. The majority said that they were at least somewhat satisfied with their retirement benefits. But a substantial number, especially many younger workers, indicated they were unsure what type of retirement plan their government employers offered.

Sixty-nine percent said they were very or somewhat confident they would have enough money to live comfortably in retirement, compared with 55 percent of Americans surveyed in a separate study in January of 2014.3 Female public employees were less likely than men to express confidence in their retirement situation: 63 percent of women said they were very or somewhat confident, compared with 77 percent of men.

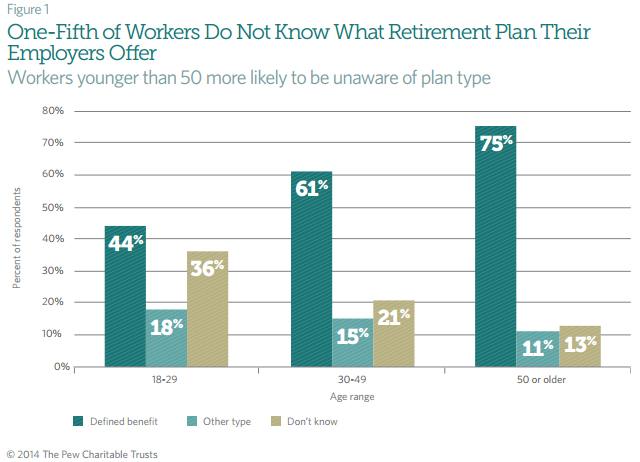

One-fifth of state and local workers polled said they did not know what type of retirement plan their employers offered. Women were more likely to say this—23 percent—compared with 15 percent of men. In addition, workers younger than 50 were more likely to report that they did not know what type of retirement plan they had than were workers 50 or older. (See Figure 1.)

Importance of job-related factors

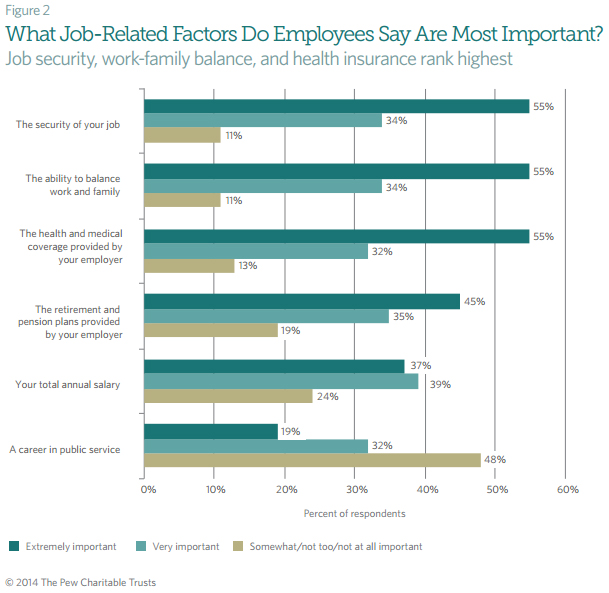

The survey asked workers to rate the importance of various factors related to a job. Workers could rank each as extremely important, very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important. Fifty-five percent of respondents said job security, work-family balance, and health insurance were extremely important. Forty-five percent listed retirement and pension plans as extremely important, and 37 percent said total annual salary was extremely important. Nearly half rated a career in public service as no more than somewhat important. (See Figure 2.)

Fewer younger workers said retirement plans were extremely important. Only 33 percent of those younger than 30 said retirement plans were extremely important to them, compared with 44 percent of workers ages 30 to 49 and 51 percent of those 50 and older.

More than half—55 percent—of state and local workers said they would prefer a job that offers more generous retirement benefits in exchange for a somewhat lower salary. Meanwhile, 41 percent said they would swap a somewhat higher salary for less-generous retirement benefits.

But these percentages vary by workers’ age. Half of workers younger than 50 said they would prefer the lower-salary, higher-retirement-benefit package, compared with 63 percent of workers 50 and older. Forty-six percent of workers younger than 50 said they would prefer a higher salary and lower retirement benefit, compared with 33 percent of older workers. Workers younger than 30 were most likely to say they preferred a higher salary in exchange for less-generous retirement benefits; 53 percent selected this option. 4

Satisfaction with retirement system

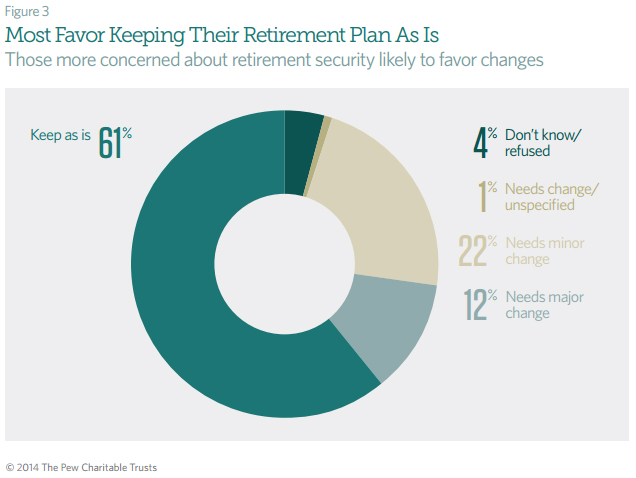

Thirty-five percent of respondents said their employer’s retirement system needed changes, including 12 percent who said it needed major changes. Sixty-one percent said they thought it should be kept as it is. Those with lower confidence in their ability to live comfortably in retirement were more likely to say they would like to see changes. So were women—38 percent—compared with men—30 percent. (See Figure 3.)

A large majority of state and local government workers said they were at least somewhat satisfied with their retirement benefits and salary. Eighty-five percent said they were somewhat or very satisfied with the retirement benefits provided by their employer, including 34 percent who reported being very satisfied. Seventy-two percent said they were very or somewhat satisfied with their salary, including 21 percent who said they were very satisfied. In total, 67 percent of respondents said they were at least somewhat satisfied with both their salary and retirement benefits.

Workers who listed lower household incomes reported considerably less satisfaction with their salary and somewhat less with their retirement benefits than respondents who reported higher household incomes. Among workers with household income under $50,000, 42 percent said they were not too or not at all satisfied with their salary, compared with 22 percent of those with household incomes of $50,000 or more. Twenty percent of those lower-income workers expressed dissatisfaction with their retirement benefits, compared with 12 percent of higher-income employees.

Men reported higher levels of satisfaction with both salary and retirement benefits than women: Twenty-six percent of male respondents said they were very satisfied with their salary, compared with 17 percent of women. And 39 percent of men said they were very satisfied with their retirement benefits, compared with 30 percent of women. There wasn’t much difference on these measures by age, although workers 50 or older were more likely to report being very satisfied with their salary.

Work and retirement expectations

Slightly more than half—54 percent—of state and local public workers said they expected to retire at age 65 or later. Of this group, 25 percent said they expected to retire at 65, and 29 percent said they expected to retire after 65. An additional 4 percent of respondents volunteered that they do not ever expect to fully retire.4 These results are similar to findings in a national survey completed by the Employee Benefit Research Institute in 2014 that reported 56 percent of adults polled said they expected to retire at or after age 65, and 10 percent volunteered that they didn’t expect to ever retire fully.

State and local employees said retirement-plan design affects decisions on when to stop working. Eighty percent said they think some government employees who want to leave their jobs keep working until retirement age so they won’t lose retirement benefits. That includes 60 percent who said they thought this happens a lot. Fifty-six percent said they thought some workers retire earlier than they would like in order to maximize retirement benefits, including 31 percent who think this happens a lot. Overall, 88 percent of respondents said they thought workers either worked longer or retired earlier than their preference in order to maximize retirement benefits, including 48 percent who thought both things happen.5

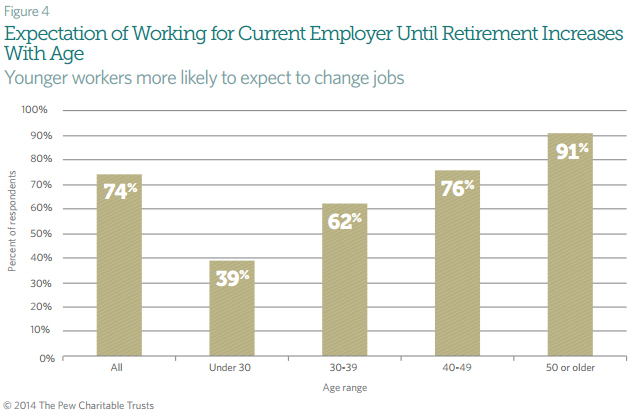

Fifty-seven percent of state and local employees said they had been working in government for more than 10 years, including 26 percent who said they had been on the job at least 20 years. In addition, almost three-quarters of state or local employees said they expected to work for their current employer until retirement.

Seventy-three percent of teachers and 78 percent of public safety workers said they expected to stay with their current employer until retirement. Younger workers, with most of their careers still ahead of them, were more likely to expect to change jobs. But even among those younger than 30, 39 percent said they expected to work for their current employer until they retire. Not unexpectedly, that expectation increases with age—62 percent of workers ages 30 to 39, 76 percent of workers ages 40 to 49, and 91 percent of workers 50 or older said they expected to stay with their current employer until retirement. (See Figure 4.)

About the survey

This survey is based on telephone interviews by SSRS between Aug. 15 and Nov. 24, 2013, of a national sample of 2,110 adults employed full time by a state or local government, living in every state and the District of Columbia. Qualified respondents were identified from screening interviews with 55,170 randomly selected adults.

Acknowledgement

Pew’s work on public-sector retirement systems is conducted in partnership with the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Endnotes

- National Conference of State Legislators, “State Retirement Reform Legislation,” presentation to the Louisiana Association of Public Employees’ Retirement Systems, Sept. 16, 2013, http://www.lapers.org/PDFs/2013 Presentations/State Retirement Reform Legislation.pptx.

- This survey included only current state and local workers. The views of former state or local workers are not represented in these findings.

- Employee Benefit Research Institute, “2014 Retirement Confidence Survey,” accessed April 14, 2014, http://www.ebri.org/pdf/surveys/rcs/2014/RCS14.FS-1.Conf.Final.pdf.

- Most public workers are eligible for retirement benefits before age 65, and data on actual retirements suggests that on average, public workers retire from public pension plans before reaching age 65. Mike Maciag, “Public Sector Has Some of Oldest Workers Set To Retire,” Governing, August 26, 2013, http://www.governing.com/blogs/by-the-numbers/gov-aging-public-sector-has-some-of-oldest-workersset-to-retire.html.; Robert M. Costrell and Michale Podgursky, “Teacher Retirement Benefits,” Education Next, Spring 2009, http://educationnext.org/teacher-retirement-benefits/.

- In some cases, workers may retire earlier than they would otherwise choose, because once they reach their plans’ normal retirement age, the value of their benefits increases slowly, making it more expedient to retire immediately and collect a pension for more years than to continue working.