How Corporate Control Squeezes Out Small Farms

Competition is a critical element of our free market economy and is particularly important in agriculture. Consumers understand almost instinctively that market domination by a single powerful business can lead to higher prices. Less obvious is the role that lack of competition has played in squeezing out small and midsize farms and ranches and in changing the nature of animal agriculture across the country.

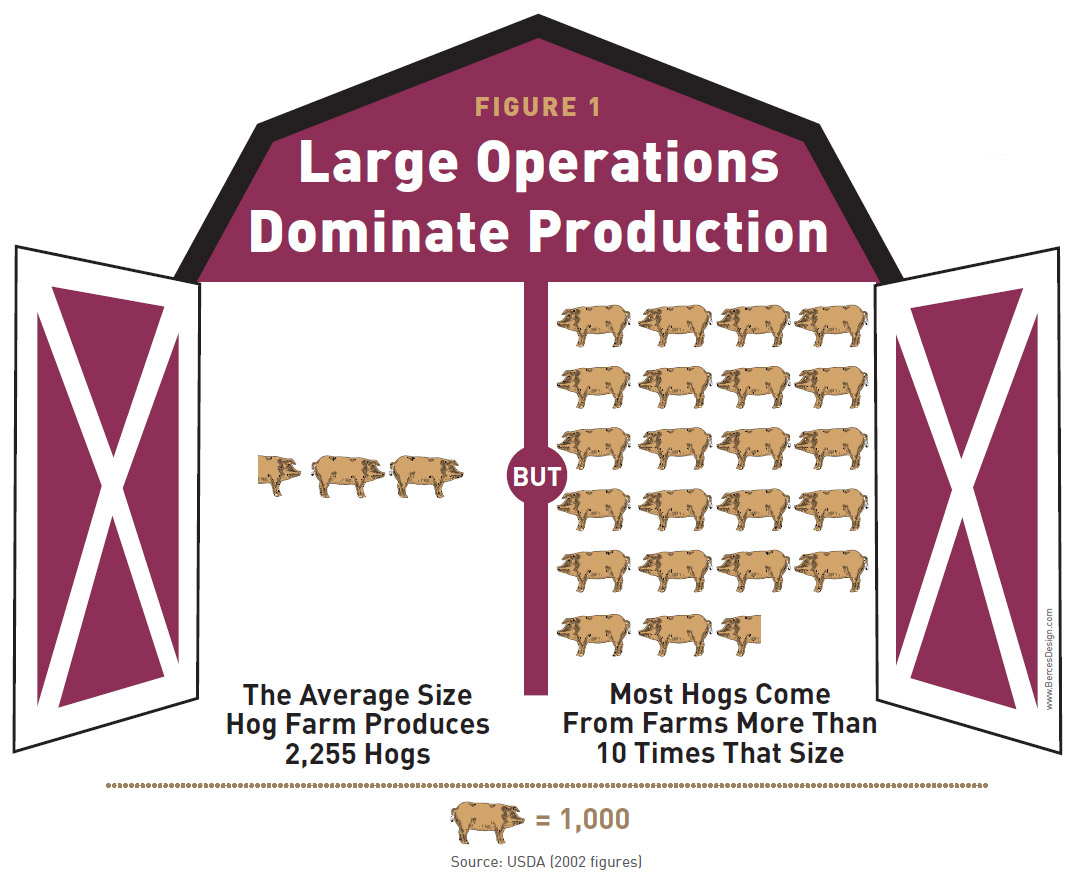

Over the past 50 years, the United States has lost more than a million farms, yet more animals than ever are being raised, slaughtered, and processed. The modern operations that raise most animals for food today are far larger than those of years ago, and many specialize in only one type of livestock or even one stage of an animal's life. The very largest of these now account for a huge proportion of production. In 2002, for example, the average U.S. hog farm produced 2,255 animals, but most of the hogs produced in the country came from operations more than 10 times that large. In the same year, most of the cows sold in the United States came from operations selling more than 34,000 head, and most of the broiler chickens came from operations that produced more than 500,000 birds.

Many large operations have relatively little cropland and are often geographically concentrated in certain areas, particularly around meatpacking and processing plants. As the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has pointed out, these larger facilities now produce excess amounts of waste and are “also more prone to use antibiotics intensively in order to pre-empt the spread of animal disease and to accelerate animal growth.” This contrasts with more traditional diversified farms, which maintained a balanced mix of crops and livestock.

The Structure of Livestock Agriculture

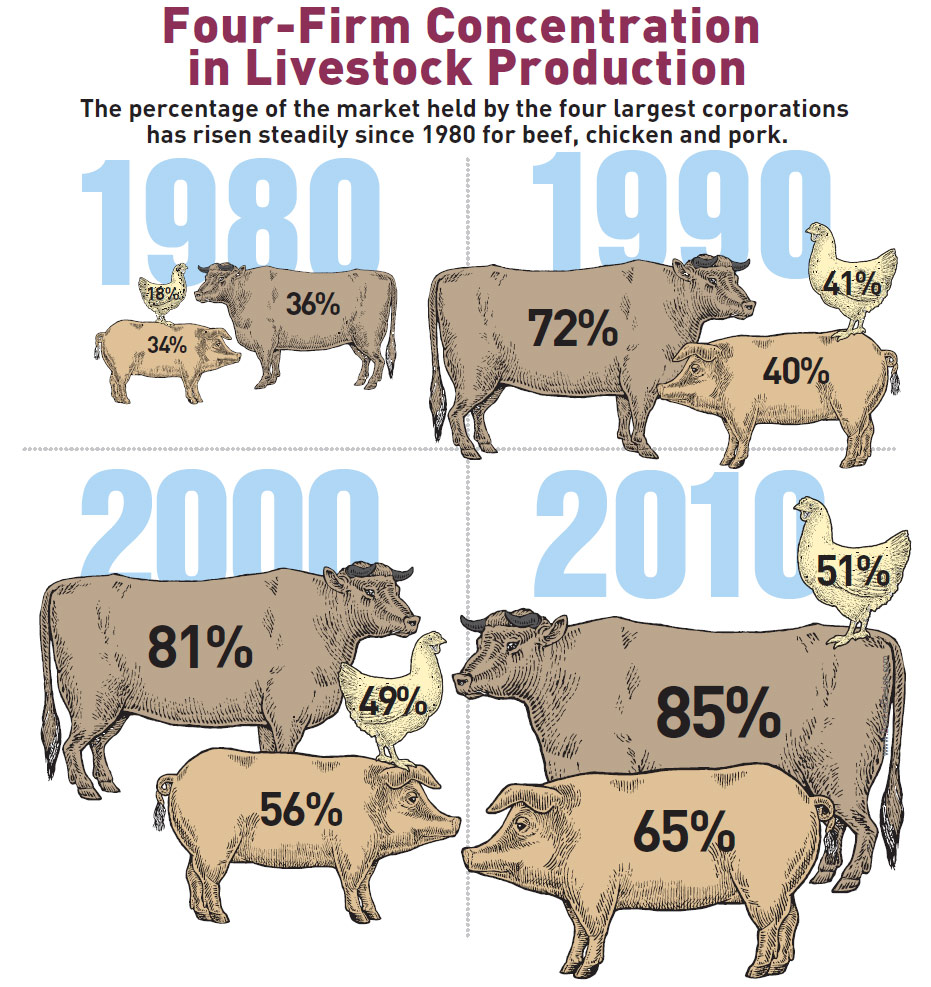

Consolidation in the livestock industry has occurred through mergers, acquisitions, and the demise of small businesses, and today's market reflects the dominance of a relative handful of large entities that control the slaughter, processing, and marketing of most livestock. A look at the “fourfirm concentration”—a common measure of market dominance by the top firms in an industry—shows the long-term trend toward consolidation in the meat industry.

Consolidation in the livestock industry has occurred through mergers, acquisitions, and the demise of small businesses, and today's market reflects the dominance of a relative handful of large entities that control the slaughter, processing, and marketing of most livestock. A look at the “fourfirm concentration”—a common measure of market dominance by the top firms in an industry—shows the long-term trend toward consolidation in the meat industry.

Today, large meatpackers may own livestock outright and hence can manage their inventory to affect and respond to market prices, potentially to the detriment of smaller producers. Other processors (also known as integrators) use production contracts, under which they retain ownership of the animals and contract with farmers to raise them. This type of contract, which generally allows the processor to dictate how and when animals will be raised, now dominates in the broiler business and is becoming increasingly common with hogs. At the same time, more of the livestock business has become vertically integrated, with large corporations controlling most or all stages of production, from livestock genetics to grocery store packaging.

The result is the disappearance of open and competitive livestock markets: In 2010, for example, about 35 percent of all cattle were sold on the spot market, down from 45 percent in 2001. In 2010, the spot market for hogs was only 8 percent; just 15 years ago, it was 62 percent. For commercial broiler production, there is virtually no spot market at all.

This transformation in livestock agriculture has led to concerns about the economic leverage that large corporations hold over independent farmers and ranchers. Early in 2010, the USDA and the Department of Justice initiated an unprecedented series of joint public workshops around the country to investigate the state of competition in agriculture markets. Hundreds of independent livestock producers attended the workshops, and many testified that it is increasingly difficult to survive economically. They urged the USDA's Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) to better regulate the anti-competitive practices of large agribusiness. Their pleas were echoed by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA): “The agriculture industry has consolidated to the point where family farmers, independent producers, and other smaller market participants do not have equal access to fair and competitive markets.”

Reforming Market Policies

Reforming Market Policies

Policymakers have long recognized that livestock markets are particularly vulnerable to manipulation, and the 1921 Packers and Stockyards Act (PSA) was enacted to curtail unfair, fraudulent, or deceptive practices by meatpackers and processors. Over the years, however, enforcement of the PSA, and its relevance to the rapidly changing meat industry, has been a source of concern for farmers and has fostered vigorous debate among policymakers.

In 2010, the GIPSA proposed rules, as required by the 2008 Farm Bill, intended to protect independent farmers and help reduce the power of consolidated meatpackers. In August 2010, a bipartisan letter from 21 senators to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack urged speedy adoption of these regulations, but the final rule, released in December 2011, contained only a few of the needed reforms.

The initial proposal, for example, would have made it clear that certain agricultural contracting and payment practices could be found to be unfair or deceptive and hence illegal without a showing of harm to the entire marketplace. It would have required justification for packers and processors offering different payment premiums to different producers; banned certain packer-to-packer sales of animals that could suppress the prices received by independent producers; and required disclosure of basic contract provisions to the USDA. None of those reforms was adopted.

The agriculture industry has consolidated to the point where family farmers, independent producers, and other smaller market participants do not have equal access to fair and competitive markets.Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA)

In the final rule, the USDA did include a requirement for processors to offer written notice of intent to suspend delivery of live birds to a poultry grower; disclosure requirements for contracts that call for arbitration to settle disputes; and some limitations on the extent to which processors can demand unnecessary capital improvements to on-farm facilities. The final rule also required contractors to give growers a reasonable amount of time to resolve any potential breach-of-contract problems. Unfortunately, some members of Congress are pressing to rescind some of these protections.

Although the final rule failed to provide adequate relief to contract growers and independent operations, Congress and the administration can still act to secure a level playing field for America's animal agriculture industry. The Pew Environment Group's Campaign to Reform Industrial Animal Agriculture is advocating for full enforcement of the PSA, antitrust laws, and other farm fairness laws as a first step in returning fair competition to the livestock market. In addition, the campaign is working to expose the effects of corporate control by integrators on rural communities and is calling for increased transparency in contracting practices and shared responsibility for CAFO waste management.

Farmers Speak Out

Read stories from farmers and ranchers fighting to reform industrial animal agriculture.