Small Mortgages Are Too Hard to Get

A shortage of loans for homes priced below $150,000 bars many American families from homeownership

Editor’s note: This brief was updated July 3, 2023, to recognize the peer reviewers and Pew staff members who contributed to its development.

Overview

Mortgages are essential financial tools that create a pathway to homeownership for millions of Americans each year. In recent years, however, many homebuyers have struggled to obtain small mortgages to purchase low-cost homes, those priced under $150,000.1 This problem has garnered the attention of federal regulators, including the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), who view small mortgages as important tools to increase wealth-building and homeownership opportunities in financially undeserved communities.2

Research has explored mortgage access at different loan amounts, such as below $100,000 or $70,000, and found that small mortgages are scarce relative to larger home loans. Those analyses show that applications for small mortgages are more likely to be denied than those for larger loans, even when applicants have similar credit scores.3 Although the existing research has identified several possible contributing factors to the shortage of small mortgages, the full spectrum of causes and their relative influence are not well understood.4

The Pew Charitable Trusts set out to fill that gap by examining the availability of small mortgages nationwide, the factors that impede small mortgage lending, and the options available to borrowers who cannot access these loans. Pew researchers compared real estate transaction and mortgage origination data from 2018 to 2021 in 1,440 counties across the U.S.; looked at homeownership statistics; and reviewed the results from Pew’s 2022 survey of homebuyers who have used alternative financing methods, such as land contracts and rent-to-own agreements.5 (See the separate appendices document for more details.) This examination found that:

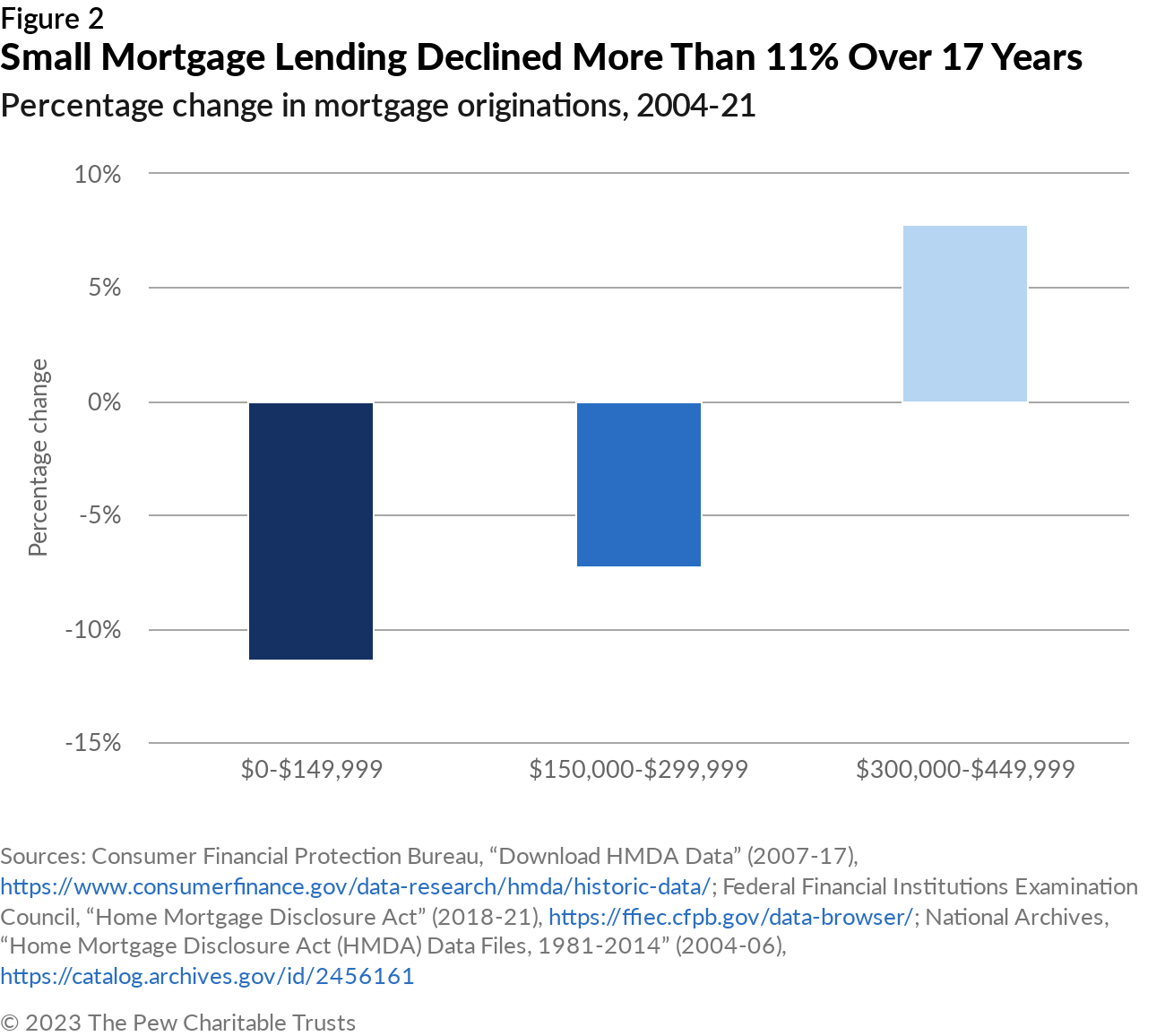

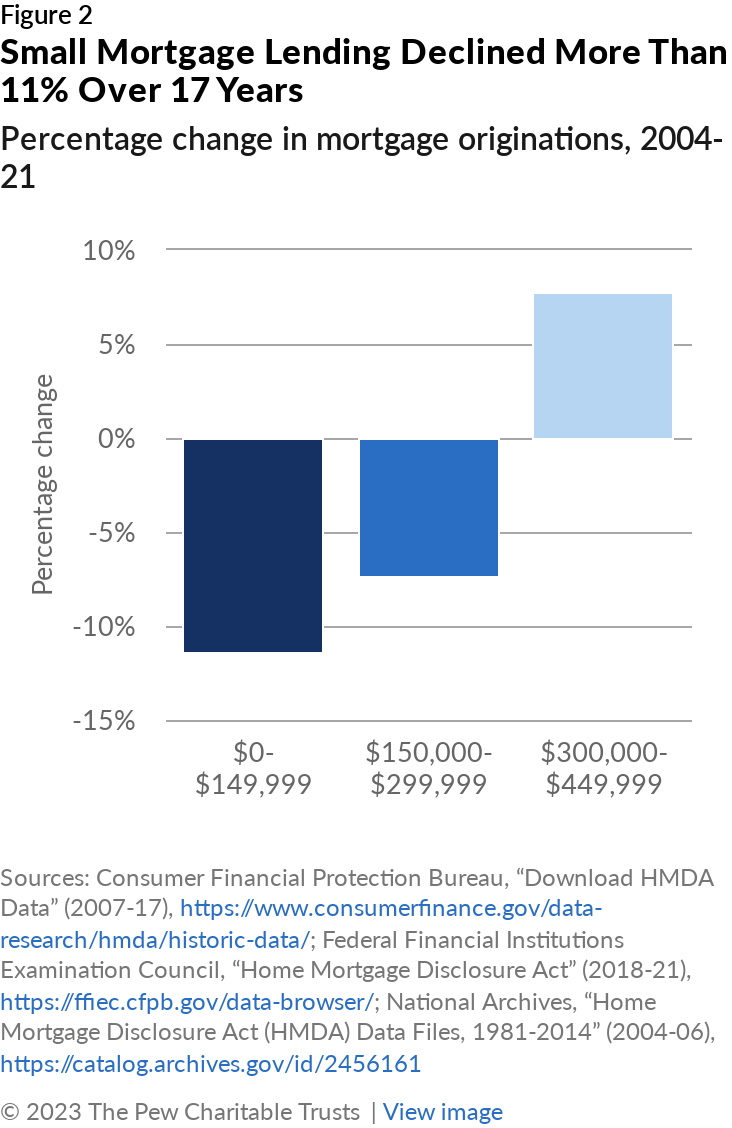

- Small mortgages became less common from 2004 to 2021. Nationally, much of the decline in small mortgage lending is the result of home price appreciation, which continually pushes properties above the price threshold at which small mortgages could finance them. However, even after accounting for price changes, small mortgages are less available nationwide than they were two decades ago, although the decline varies by geography.

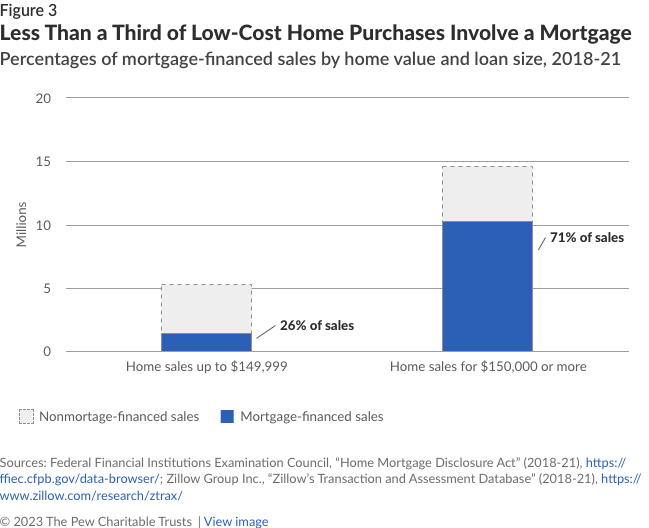

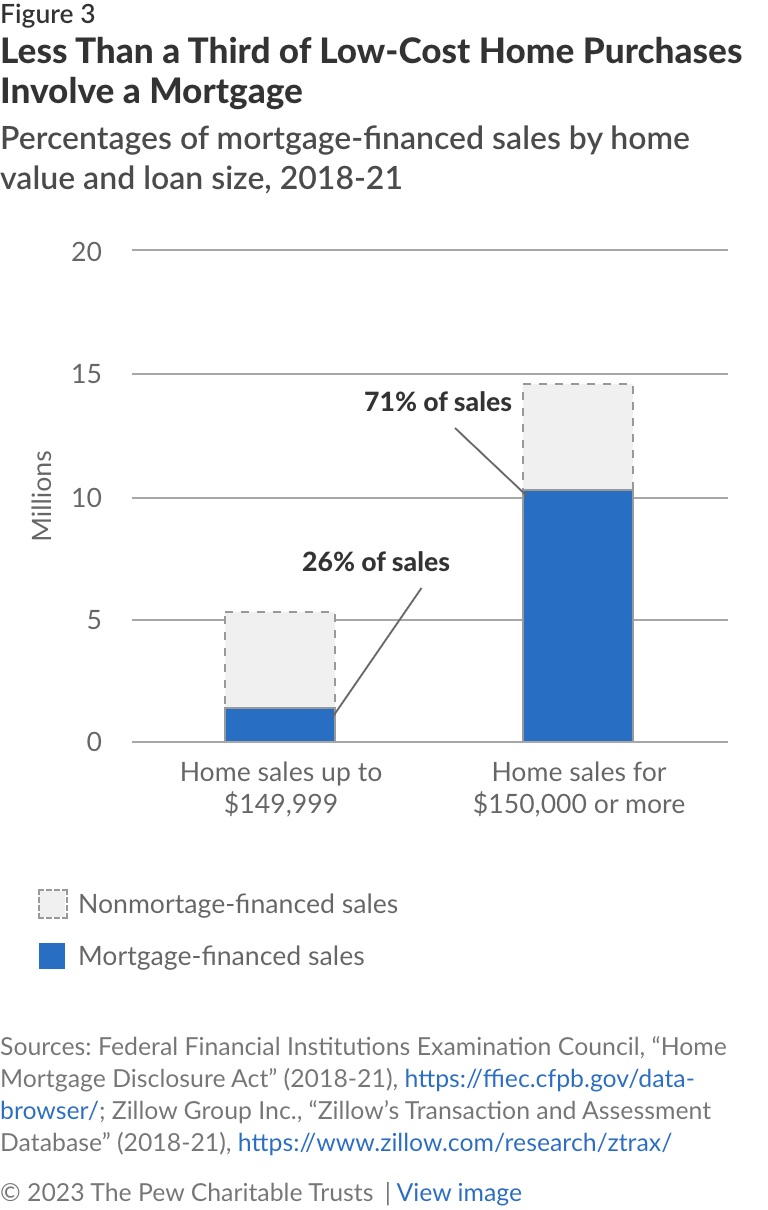

- Most low-cost home purchases do not involve a mortgage. Despite rising prices, sales of low-cost homes remain common nationwide, accounting for more than a quarter of total sales from 2018 to 2021. However, just 26% of properties that sold for less than $150,000 were financed using a mortgage, compared with 71% of higher-cost homes.

- Borrowers who cannot access small mortgages typically experience one of three undesirable outcomes. Some households cannot achieve homeownership, which deprives them of one of this nation’s key wealth-building opportunities. Others pay for their home purchase using cash, though this option is challenging for all but the most well-resourced households and is almost never available to first-time homebuyers. And, finally, some resort to alternative financing arrangements, which tend to be riskier and costlier than mortgages, because in most states they are poorly defined and not subject to robust—or sometimes any—consumer protections.

- Structural and regulatory barriers limit the profitability of small mortgage lending. The most significant of these barriers is that the fixed costs of originating a mortgage are disproportionally high for smaller loans. Federal policymakers can help address these challenges by identifying opportunities to modernize certain regulations in ways that reduce lenders’ costs without compromising borrower protections.

Mortgages are the main pathway to homeownership

In the United States, homeownership remains a priority for most families: In one nationally representative survey, 74% of respondents said owning a home is an integral part of the American Dream.6 Some Americans value homeownership for personal reasons, citing it as a better option for their family, their sense of safety and security, and their privacy.7 Still others emphasized homeownership’s financial benefits, noting that owning makes more economic sense than renting, enables them to take advantage of their home’s resale value, and can provide substantial tax benefits.8

But regardless of their reasons for buying homes, most American families rely on mortgages to gain access to homeownership because they cannot afford to purchase a home with cash. According to a survey conducted from July 2021 to June 2022, 78% of homebuyers financed their purchases with mortgages, most of which were fixed-rate loans. Mortgages are even more prevalent among first-time homebuyers: 97% used a mortgage to purchase their starter home.9 Given the predominance of mortgages, it is no surprise that changes in mortgage availability have closely correlated with shifts in the nation’s homeownership rate over the past two decades.10 (See Figure 1.)

Mortgages not only enable homeownership, but they also enhance its financial benefits. In most cases, these loans help borrowers purchase larger or more valuable homes than they could otherwise afford. Fixed-rate mortgages also serve as a hedge against inflation and offer borrowers housing cost certainty in the form of a predictable schedule of payments for the duration of the loan.

In addition, mortgages are subject to robust consumer protections. Most mortgages include inspection and appraisal contingencies, which ensure that homes meet minimum habitability standards and that the sale price reflects the home’s true market value, respectively.11 Further, real estate transactions involving mortgages typically include a clear process for transferring the property’s title from seller to buyer, which is a crucial step in guaranteeing that borrowers can demonstrate ownership of their property. And in the event of default, CFPB rules contain clear foreclosure and delinquency processes that give mortgage borrowers an opportunity to make any missed payments and retain their homes.12

Because of these advantages, financing a home purchase with a mortgage is almost always in buyers’ best interest. However, homebuyers seeking loans under $150,000 are often unable to find a mortgage and so are deprived of the benefits of homeownership, of mortgages, or both.

Small mortgages are scarce

Small mortgages are less common today than they were before the Great Recession, when lenders issued small and large mortgages in roughly equal measure. In 2004, for example, lenders originated 2.7 million mortgages for less than $150,000 (in 2004 dollars) and 2.9 million large mortgages—those of $150,000 or more. But Pew estimates that from 2004 to 2021, small mortgage lending fell by nearly 70% to 830,000 loans a year, while large mortgage lending grew by 52% to 4.4 million loans annually. The decline was more acute in certain parts of the country. For instance, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that small mortgages declined by only 28% in Pennsylvania and Delaware from 2019 to 2021 but fell by 43% in New Jersey over the same span.13

Some of the decrease in small mortgage lending can be explained by rising home prices. As homes become more expensive, fewer properties can be purchased using a small mortgage. And the issue of housing affordability has grown more acute over the past two decades. According to the Zillow Home Value Index, single-family home prices rose faster than the rate of inflation from 2004 to 2021. Furthermore, those increases were largest among lower-priced homes.14 Still, home price appreciation does not fully account for the decline in small mortgage lending. (See Figure 2.)

Although low-cost properties are scarcer than they once were, they continue to be bought and sold in large numbers across the country. But the share of those homes purchased with a mortgage is far lower than that for higher-priced properties. From 2018 to 2021, the 1,440 counties Pew studied collectively recorded about 20 million home sales, of which 5.3 million were for less than $150,000. Although the share of low-cost properties varied based on local market conditions, every county in this analysis recorded at least one low-cost sale. During the same period, lenders originated about 12.1 million mortgages in the counties Pew studied, including roughly 1.4 million for purchases under $150,000.15 Based on these mortgage origination and home sale figures, Pew estimates that about 71% of homes priced at $150,000 or more were financed using a mortgage, compared with just 26% of lower-cost homes. (See Figure 3.) This amounts to a financing gap of 44 percentage points, or about 560,000 home purchases that were not financed with small mortgages.

Importantly, however, this analysis probably overstates the magnitude of the financing gap for two key reasons. First, Pew is unable to observe the physical quality of the homes purchased in the studied counties. Evidence suggests that low-cost homes are more likely than higher-cost homes to have structural deficiencies that disqualify them from mortgage financing. Second, even if small mortgages are readily available, many sellers, and probably some buyers, are likely to prefer cash transactions. (See “Cash purchases” below for more details.) Still, these factors do not fully account for the gap in small mortgage financing.

What happens when people cannot get a small mortgage?

When prospective buyers of low-cost homes cannot access a small mortgage, they typically have three options: turn to alternative forms of financing such as land contracts, lease-purchases, or personal property loans; purchase their home using cash; or forgo owning a home and instead rent or live with family or friends. Each of these outcomes has significant disadvantages relative to buying a home using a small mortgage.

Alternative financing

Many alternative financing arrangements are made directly between a seller and a buyer to finance the sale of a home and are generally costlier and riskier than mortgages.16 For example, personal property loans—an alternative arrangement that finances manufactured homes exclusive of the land beneath them—have median interest rates that are nearly 4 percentage points higher than the typical mortgage issued for a manufactured home purchase.17 Further, research in six Midwestern states found that interest rates for land contracts—arrangements in which the buyer pays regular installments to the seller, often for an agreed upon period of time—ranged from zero to 50%, with most above the prime mortgage rate.18 And unlike mortgages, which are subject to a robust set of federal regulations, alternative arrangements are governed by a weak patchwork of state and federal laws that vary widely in their definitions and protections.19

But despite the risks, millions of homebuyers continue to turn to alternative financing. Pew’s first-of-its-kind survey, fielded in 2021, found that 36 million people use or have used some type of alternative home financing arrangement.20 And a 2022 follow-up survey on homebuyers’ experiences with alternative financing found that these arrangements are particularly prevalent among buyers of low-cost homes. From 2000 to 2022, 50% of borrowers who used these arrangements purchased homes under $150,000. (See the separate appendices document for survey toplines.)

Further, the 2022 survey found that about half of alternative financing borrowers applied—and most reported being approved or preapproved—for a mortgage before entering into an alternative arrangement. Pew’s surveys of borrowers, interviews with legal aid experts, and review of research on alternative financing shed some light on the advantages of alternative financing—despite its added costs and risks—compared with mortgages for some homebuyers:

- Convenience. Alternative financing borrowers do not have to submit or sign as many documents as they would for a mortgage, and in some instances, the purchase might close more quickly.21 For example, Pew’s 2022 survey found that just 67% of respondents said they had to provide their lender with bank statements, pay stubs, or other income verification and only 60% had to furnish a credit report, credit score, or other credit check, all of which are standard requirements for mortgage transactions.

- Upfront costs. Some alternative financing arrangements have lower down payment requirements than do traditional mortgages.22 Borrowers who are unable to afford a substantial down payment or who want small monthly payments may find alternative financing more appealing than mortgages, even if those arrangements cost more over the long term. For example, in Pew’s 2022 survey, 23% of respondents said they did not pay a down payment, deposit, or option fee. And among those who did have a down payment, 75% put down less than 20% of the home price, compared with 59% of mortgage borrowers in 2021.23

- Specifics of a home. Borrowers who prioritize the location or amenities of a specific home over the type, convenience, and cost of financing they use might agree to an alternative arrangement if the seller insists on it, rather than forgo purchasing the home.

- Familiarity with seller. Borrowers buying a home from family or friends might agree to a transaction that is preferable to the seller because they trust that family or friends will give them a fair deal, perhaps one that is even better than they would get from a mortgage lender.

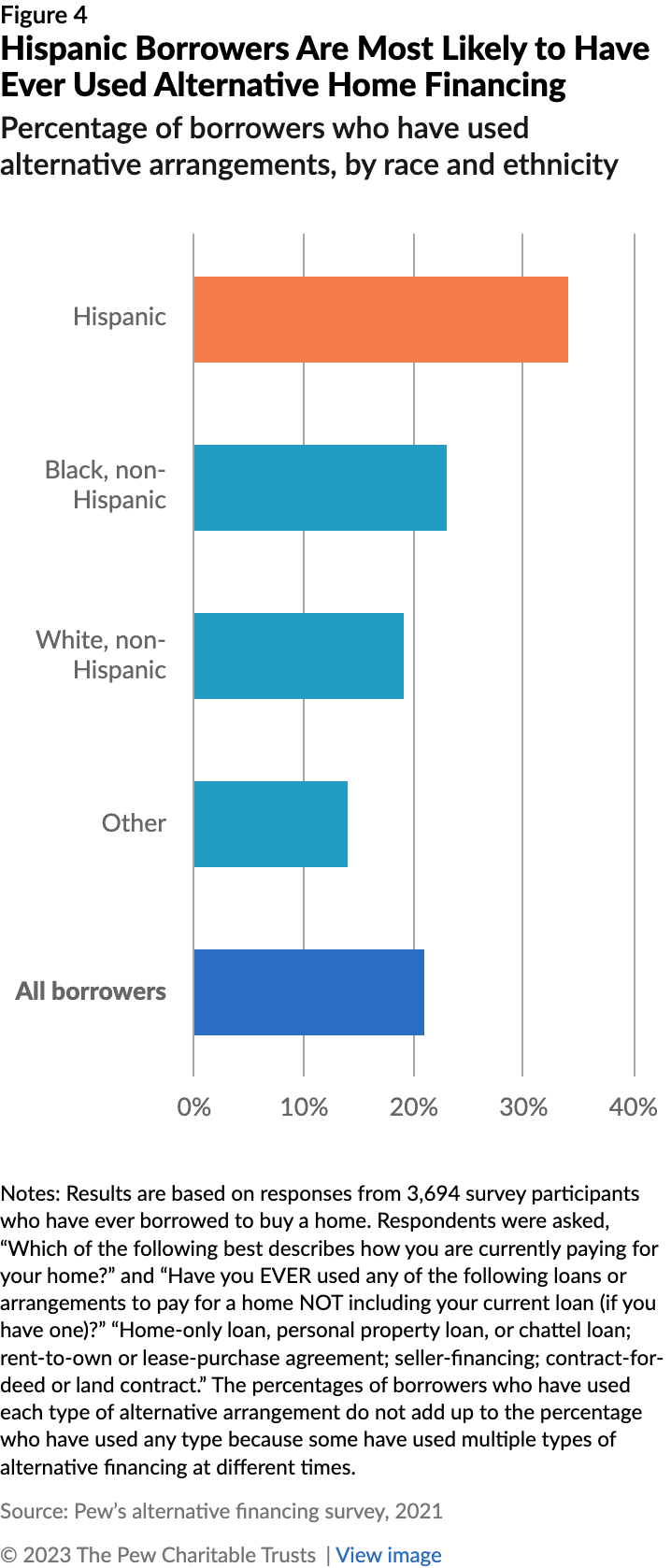

However, regardless of a borrower’s reasons, the use of alternative financing is cause for concern because it is disproportionately used—and thus the risks and costs are inequitably borne—by racial and ethnic minorities, low-income households, and owners of manufactured homes. Among Americans who have financed a home purchase, 34% of Hispanic and 23% of Black households have used alternative financing at least once, compared with just 19% of White borrowers. (See Figure 4.) Further, families earning less than $50,000 are seven times more likely to use alternative financing than those earning more than $50,000. And nearly half of surveyed manufactured home owners reported using a personal property loan.24 In all of these cases, expanding access to small mortgages could help reduce historically underserved communities’ reliance on risky alternative financing arrangements.

Cash purchases

Other homebuyers who fail to obtain a small mortgage instead choose to pay cash for their homes. In 2021, about a quarter of all home sales were cash purchases, and that share grew in 2022 amid an increasingly competitive housing market.25 The share of cash purchases is larger among low-cost than higher-cost property sales, which may partly be a consequence of the lack of small mortgages.26 However, although cash purchases are appealing to some homebuyers and offer some structural advantages, especially in competitive markets, they are not economically viable for the vast majority of first-time homebuyers, 97% of whom use mortgages.27

Purchasing a house with cash gives buyers a competitive advantage, compared with using a mortgage. Sellers often prefer to work with cash buyers over those with financing because payment is guaranteed, and the buyer does not need time to secure a mortgage. Cash purchases also enable simpler, faster, and cheaper sales compared with financed purchases by avoiding lender requirements such as home inspections and appraisals. In essence, cash sales eliminate “financing risk” for sellers by removing the uncertainties and delays that can accompany mortgage-financed sales. Indeed, as the housing supply has tightened and competition for the few available homes has increased, purchase offers with financing contingencies have become less attractive to sellers. As a result, some financing companies have stepped in to make cash offers on behalf of buyers, enabling those borrowers to be more competitive but often saddling them with additional costs and fees.

However, most Americans do not have the financial resources to pay cash for a home. In 2019, the median home price was $258,000, but the median U.S. renter had just $15,750 in total assets—far less than would be necessary to buy a house.28 Even households with cash on hand may be financially destabilized by a cash purchase because investing a substantial sum of money into a home could severely limit the amount of money they have available for other needs, such as emergencies or everyday expenses. Perhaps because of the financial challenges, homes purchased with cash tend to be smaller and cheaper than homes bought using a mortgage.29

These challenging economic factors limit the types of homebuyers who pursue cash purchases. Investors—both individual and institutional—make up a large share of the cash-purchase market, and are more likely than other buyers to purchase low-cost homes and then return the homes to the market as rental units.30

Researchers have questioned whether cash purchases are truly an alternative to mortgage financing or whether they fundamentally change the composition of homebuyers. One study conducted in 2016 determined that tight credit standards enacted in the aftermath of the 2008 housing market crash resulted in a large uptick in cash purchases, mostly by investor-buyers.31 More recent evidence from 2020 through 2021 suggests that investor purchases are more common in areas with elevated mortgage denial rates, low home values, and below-average homeownership rates.32 In each of these cases, a lack of mortgage access tended to benefit investors, possibly at the expense of homeowners.

No homeownership

Some prospective homebuyers who are unable to access a small mortgage simply forgo homeownership entirely. Instead of buying, these families may choose to rent or live with friends or family. And although these are not necessarily bad outcomes, they lack the financial advantages of homeownership.

On average, homeowners have a net worth that is more than 40 times that of renters, largely because of the equity they accrue from paying down their mortgage balances and from their homes’ appreciation over time.33 In 2019, the median homeowner had $225,000 of equity, accounting for almost 90% of their overall net worth.34

Further, in rental markets with few vacancies and commensurately high costs, owning a home can cost less per month than renting. Recent evidence suggests that, particularly when mortgage interest rates are low, a mortgage payment for a three-bedroom house can be cheaper than the monthly rent for a three-bedroom apartment.35 Likewise, some evidence suggests that buying an inexpensive starter home costs less than renting in some metropolitan areas in the South and Midwest.36

Importantly, the financial benefits of homeownership are not shared equally throughout the country. Historical patterns of discrimination in mortgage lending and government policy have prevented Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous households from accessing homeownership at the same rate as White households. And many of those structural barriers persist, as evidenced by the Black-White homeownership gap, which was wider in 2020 than it was in 1970.37

Mortgage Denials Play a Small Role in Low Access to Credit

Lenders deny applications for small mortgages more often than those for larger loans. From 2018 to 2021, lenders received about 700,000 small mortgage applications per year for site-built single-family homes, of which they denied 11.8%. In contrast, lenders denied just 7.8% of the roughly 3.6 million applications submitted annually for larger mortgages during the same period.

These differences do not entirely reflect applicants’ creditworthiness, as measured by debt-to-income ratio (a person’s monthly debt divided by their income), loan-to-value ratio (dollar amount of a mortgage as a share of the subject property’s appraised value), or credit scores. Research demonstrates that, even for applicants with similar credit profiles, denial rates are much higher for small mortgages than large ones.38 Pew’s analysis confirms these findings. Lenders denied small mortgage applicants with low debt-to-income ratios (36% and below) 8.8% of the time, compared with 4.7% of the time for larger loan applicants with a similar profile. Likewise, applicants with loan-to-value ratios under 80% were more likely to be denied for a small mortgage than a large one.

However, mortgage denials are not the primary cause of the small mortgage shortage. Pew’s analysis found that if lenders denied applications for small mortgages at the same rate as those for larger mortgages, they would originate about 31,000 more small mortgages each year. Although thousands of borrowers would benefit from lower small mortgage denial rates, those additional loans would increase the share of low-cost properties financed with a mortgage by only about 3 percentage points. These findings suggest that lowering the denial rate is not sufficient to increase access to safe and affordable mortgage financing and that regulators need to do more to improve incentives for lenders to originate small mortgages and boost awareness among borrowers.

Small mortgage lending is not profitable for lenders

Policymakers, consumer advocates, and industry agree that increasing the supply of small mortgages could boost homeownership—especially in underserved, low-cost communities.39 But many mortgage lenders simply do not offer small home loans to borrowers. Of the more than 5,000 lenders that originated mortgages from 2018 to 2021, 38% did not issue a single small mortgage.40

In conversations with Pew, lenders, consumer advocates, and government officials identified several potential structural and regulatory obstacles to small mortgage lending. These include the high fixed cost of origination, commission-based compensation for loan officers, the poor physical quality of many low-cost housing units, and various rules and regulations that help protect consumers but may add cost or complexity to the origination process and could be updated to maintain safety at lower cost to lenders.

Structural barriers

Lenders have repeatedly identified the high fixed cost of mortgage originations as a barrier to small mortgage lending because origination costs are roughly constant regardless of loan amount, but revenue varies by loan size. As a result, small mortgages cost lenders about as much to originate as large ones but produce much less revenue, making them unprofitable. Further, lenders have reported an increase in mortgage origination costs in recent years: $8,243 in 2020, $8,664 in 2021, and $10,624 in 2022.41 In conversations with Pew, lenders indicated that many of these costs stem from factors that do not vary based on loan size, including staff salaries, technology, compliance, and appraisal fees.

Lenders typically charge mortgage borrowers an origination fee of 0.5% to 1.0% of the total loan balance as well as closing costs of roughly 3% to 6% of the home purchase price.42 Therefore, more expensive homes—and the larger loans usually used to purchase them—produce higher revenue for lenders than do small mortgages for low-cost homes.

In addition, standard industry compensation practices for loan officers may limit the availability of small mortgages. Lenders typically employ loan officers to help borrowers choose a loan product, collect relevant financial documents, and submit mortgage applications—and pay them wholly or partly on commission.43 And because larger loans yield greater compensation, loan officers may focus on originating larger loans at the expense of smaller ones, reducing the availability of small mortgages.

Finally, lenders must contend with an aging and deteriorating stock of low-cost homes, many of which need extensive repairs. Data from the American Housing Survey shows that 6.7% of homes valued under $150,000 (1.1 million properties) do not meet the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of “adequacy,” compared with just 2.6% of homes valued at $150,000 or more (1.7 million properties).44 The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimates that, despite some improvement in housing quality overall, the total cost of remediating physical deficiencies in the nation’s housing stock nevertheless increased from $126.2 billion in 2018 to $149.3 billion in 2022.45

The poor physical quality of many low-cost properties can limit lenders’ ability to originate small mortgages for the purchase of those homes. For instance, physical deficiencies threaten a home’s present and future value, which makes the property less likely to qualify as loan collateral. And poor housing quality can render many low-cost homes ineligible for federal loan programs because the properties cannot meet those programs’ strict habitability standards.

Regulatory barriers

Regulations enacted in the wake of the Great Recession vastly improved the safety of mortgage lending for borrowers and lenders. But despite this success, some stakeholders have called for streamlining of regulations that affect the cost of mortgage origination to make small mortgages more viable. The most commonly cited of these are certain provisions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act), the Qualified Mortgage rule (QM rule), the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA), and parts of the CFPB’s Loan Originator Compensation rule.46

The Dodd-Frank Act requires creditors to make a reasonable, good-faith determination of a consumer's ability to repay a mortgage. This provision has significantly increased the safety of the mortgage market and protected borrowers from unfair and abusive loan terms—such as unnecessarily high interest rates and fees—as well as terms that could strip borrowers of their equity. Lenders can meet Dodd-Frank’s requirements by originating a “qualified mortgage” (QM), which is a loan that meets the CFPB’s minimum borrower safety standards, including limits on the points, fees, and annual percentage rate (APR) the lender can charge.47 In return for originating mortgages under this provision, known as the QM rule, the act provides protection for lenders from any claims by borrowers that they failed to verify the borrower’s ability to repay and so are liable for monetary damages in the event that the borrower defaults and loses the home.

Some lenders and researchers have suggested that the QM rule has increased the cost of mortgage origination because lenders had to establish new processes to verify borrowers’ ability to repay and adhere to stricter compliance requirements.48 In addition, lenders who cannot keep their charges within the QM rule limits often have to offer credits to lower the borrower-facing fees, which can result in lenders originating the loan at a loss.49 And although 2020 revisions to the QM rule gave lenders more flexibility in calculating a borrower’s ability to repay, the extent to which those changes help lenders keep origination costs in check remains unclear.

Another regulation that lenders and researchers have cited as possibly raising the cost of origination is the CFPB’s Loan Originator Compensation rule. The rule protects consumers by reducing loan officers’ incentives to steer borrowers into products with excessively high interest rates and fees. However, lenders say that by prohibiting compensation adjustments based on a loan’s terms or conditions, the rule prevents them from lowering costs for small mortgages, especially in underserved markets. For example, when making small, discounted, or reduced-interest rate products for the benefit of consumers, lenders earn less revenue than they do from other mortgages, but because the rule entitles loan officers to still receive full compensation, those smaller loans become relatively more expensive for lenders to originate. Lenders have suggested that more flexibility in the rule would allow them to reduce loan officer compensation in such cases.50 However, regulators and researchers should closely examine the effects of this adjustment on lender and borrower costs and credit availability. Although such changes would lower lenders’ costs to originate small mortgages for underserved borrowers, they also could further disincline loan officers from serving this segment of the market and so potentially do little to address the small mortgage shortage.

Lastly, some lenders have identified HOEPA as another deterrent to small mortgage lending. The law, enacted in 1994, protects consumers by establishing limits on the APR, points and fees, and prepayment penalties that lenders can charge borrowers on a wide range of loans. Any mortgage that exceeds a HOEPA threshold is deemed a “high-cost mortgage,” which requires lenders to make additional disclosures to the borrower, use prescribed methods to assess the borrower’s ability to repay, and avoid certain loan terms. Changes to the HOEPA rule made in 2013 strengthened the APR and points and fees standards, further protecting consumers but also limiting lenders’ ability to earn revenue on many types of loans. Additionally, the 2013 revision increased the high-cost mortgage thresholds, revised disclosure requirements, restricted certain loan terms for high-cost mortgages, and imposed homeownership counseling requirements.

Many lenders say the 2013 changes to HOEPA increased their costs and compliance obligations and exposed them to legal and reputational risk. However, research has shown that the changes did not significantly affect the overall loan supply but have been effective in discouraging lenders from originating loans that fall above the high-cost thresholds.51 More research is needed to understand how the rule affects small mortgages.

Regulators and lenders have taken some action to expand access to small mortgages

A diverse array of stakeholders, including regulators, consumer advocates, lenders, and researchers, support policy changes to safely encourage more small mortgage lending.52 And policymakers have begun looking at various regulations to identify any that may inadvertently limit borrowers’ access to credit, especially small mortgages, and to address those issues without compromising consumer protections.

Some regulators have already introduced changes that could benefit the small mortgage market by reducing the cost of mortgage origination. For example, in 2022, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) announced that to promote sustainable and equitable access to housing, it would eliminate guarantee fees (G-fees)—annual fees that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac charge lenders when purchasing mortgages—for loans issued to certain first-time, low-income, and otherwise underserved homebuyers.53 Researchers, advocates, and the mortgage industry have long expressed concern about the effect of G-fees on the cost of mortgages for borrowers, and FHFA’s change may lower costs for buyers who are most likely to use small mortgages.54

Similarly, FHFA’s decision to expand the use of desktop appraisals, in which a professional appraiser uses publicly available data instead of a site visit to determine a property’s value, has probably cut the amount of time it takes to close a mortgage as well as appraisal costs for certain loans, which in turn should reduce the cost of originating small loans without materially increasing the risk of defaults.55

At the same time, some lenders have been exploring the use of special purpose credit programs (SPCPs) to increase access to mortgage financing for low-cost homebuyers from historically disadvantaged communities.56 SPCPs allow lenders to design loan products that address the unique needs of borrowers of color, manufactured home buyers, and residents of areas where alternative financing is prevalent, all of whom have typically been underserved by the mortgage industry.

Other entities, such as nonprofit organizations and community development financial institutions (CDFIs), are also developing and offering small mortgage products that use simpler, more flexible underwriting methods than other mortgages, thus reducing origination costs.57 Where these products are available, they have increased access to small mortgages and homeownership, especially for low-income families and homebuyers of color.

Although these initiatives are encouraging, high fixed costs are likely to continue making small mortgage origination difficult, and the extent to which regulations governing loan origination affect—or might be safely modified to lower—these costs is uncertain. Unless policymakers address the major challenges—high fixed costs and their drivers—lenders and regulators will have difficulty bringing innovative solutions to scale to improve access to small mortgages. Future research should continue to explore ways to reduce costs for lenders and borrowers and align regulations with a streamlined mortgage origination process, all while protecting borrowers and maintaining market stability.

Solutions to small mortgage challenges in underserved communities

Structural barriers such as high fixed origination costs, rising home prices, and poor home quality partly explain the shortage of small mortgages. But borrowers also face other obstacles, such as high denial rates, difficulty making down payments, and competition in housing markets flooded with investors and other cash purchasers. And although small mortgages have been declining overall, the lack of credit access affects some communities more than others, driving certain buyers into riskier alternative financing arrangements or excluding them from homeownership entirely.

To better support communities where small mortgages are scarce, policymakers should keep the needs of the most underserved populations in mind when designing and implementing policies to increase access to credit and homeownership. No single policy can improve small mortgage access in every community, but Pew’s work suggests that structural barriers are a primary driver of the small mortgage shortage and that federal policymakers can target a few key areas to make a meaningful impact:

- Drivers of mortgage origination costs. Policymakers should evaluate federal government compliance requirements to determine how they affect costs and identify ways to streamline those mandates without increasing risk, particularly through new financial technology. As FHFA Director Sandra L. Thompson stated in April 2023: “Over the past decade, mortgage origination costs have doubled, while delivery times have remained largely unchanged. When used responsibly, technology has the potential to improve borrowers’ experiences by reducing barriers, increasing efficiencies, and lowering costs.”58

- Incentives that encourage origination of larger rather than smaller mortgages. Policymakers can look for ways to discourage compensation structures that drive loan officers to prioritize larger-balance loans, such as calculating loan officers’ commissions based on individual loan values or total lending volume.

- The balance between systemic risk and access to credit. Although advocates and industry stakeholders agree that regulators should continue to protect borrowers from the types of irresponsible lending practices that contributed to the collapse of the housing market from 2005 to 2007, underwriting standards today prevent too many customers from accessing mortgages.59 A more risk-tolerant stance from the federal government could unlock access to small mortgages and homeownership for more Americans. For example, the decision by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (known collectively as the Government Sponsored Enterprises, or GSEs) and FHA to include a positive rent payment record—as well as Freddie Mac’s move to allow lenders to use a borrower’s positive monthly bank account cash-flow data—in their underwriting processes will help expand access to credit to a wider pool of borrowers.60

- Habitability of existing low-cost housing and funding for repairs. Restoring low-cost homes could provide more opportunities for borrowers—and the homes they wish to purchase—to qualify for small mortgages. However, more analysis is needed to determine how to improve the existing housing stock without increasing loan costs for lenders or borrowers.

In addition to reducing structural and regulatory barriers to small mortgage lending, a robust policy response on home financing should focus on borrowers who are acutely affected by the lack of small mortgages. Federal policymakers should look for opportunities to expand existing programs and policies for communities that have historically been excluded from homeownership and mortgage access, particularly:

- The Duty to Serve rule, which directs the GSEs to improve access to mortgage financing for borrowers of modest means in three underserved markets: manufactured housing, rural communities, and areas requiring funds to preserve affordable housing. Homebuyers in these markets often require a small mortgage to purchase a home, so the GSEs could seek to link their Duty to Serve obligations with small mortgage lending in these markets.

- Equitable Housing Finance Plans, which are three-year strategies that the GSEs develop to promote equitable access to affordable and sustainable housing for disadvantaged groups, particularly Black and Hispanic communities. People in these communities are less likely to own a home and more likely to use alternative financing than the overall population, which probably indicates an unmet demand for mortgages. The GSE leadership should consider adding an objective to their plans related to refinancing alternative financing arrangements—which the plans’ target communities disproportionally use—into mortgages.

- SPCPs, which can help lenders better serve specific populations that would otherwise be denied credit or receive it on less favorable terms. Policymakers should encourage the creation and use of these programs for underserved populations in low-cost areas where there is a special need for small mortgages and measure the impacts.

Future Pew research will explore not only important questions about the barriers to small mortgage origination but also the strategies that policymakers can use to expand the nation’s affordable housing stock, improve the habitability of existing low-cost homes, and ensure that small mortgages are more accessible and competitive in the marketplace.

Conclusion

Mortgages are vital financial tools that enable homeownership and wealth-building opportunities for millions of Americans each year. However, the scarcity of small mortgages deprives some prospective borrowers of homeownership opportunities and drives others to buy their homes with cash or risky alternative financing arrangements.

To address this problem, policymakers should aim to expand mortgage access and the overall safety of financing for low-cost homes by reducing the structural and regulatory constraints that increase lenders’ costs and make small mortgages unprofitable, and establishing strong consumer protections for alternative arrangements. In addition, federal agencies and lawmakers can reduce racial disparities in mortgage lending by prioritizing Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous households in the development and implementation of small mortgage and alternative financing programs. Together, these initiatives would help bring homeownership opportunities to more Americans.

External reviewers

This brief also benefited from the valuable insights of Dan Gorin, lead supervisory policy analyst, Federal Reserve Board of Governors; Roberto Quercia, professor, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Craig Richardson, professor, Winston-Salem State University; and Sabiha Zainulbhai, senior policy analyst, New America. Although they reviewed drafts of the brief, neither they nor their institutions necessarily endorse the findings or conclusions.

Acknowledgments

This brief was researched and written by Pew staff members Tracy Maguze, Tara Roche, and Adam Staveski. The project team thanks current and former colleagues Nick Bourke, Ryan Canavan, Jennifer V. Doctors, David East, Anne Holmes, Alex Horowitz, Dave Lam, Omar Antonio Martínez, Cindy Murphy-Tofig, Tricia Olszewski, Reagan Ortiz, Travis Plunkett, Ryland Staples, Drew Swinburne, and Mark Wolff for providing important communications, creative, editorial, and research support for this work.

Endnotes

- Pew defines small mortgages as loans under $150,000. For the purposes of this study, loan values are adjusted for inflation to reflect 2021 dollars unless otherwise noted. This value is based on conversations with mortgage lenders and on an observed decline in lending below that threshold over the past decade. Additionally, for the purposes of this paper, low-cost homes are those priced at less than $150,000, also in 2021 dollars. This price range is consistent with the majority of purchases financed with small mortgages. The median down payment among small mortgage borrowers is just 5%, and as a result, 75% of small mortgages are used to purchase a home under $157,500, although some borrowers do pair small mortgages with larger down payments to purchase higher-cost homes.

- Request for Information Regarding Small Mortgage Lending, 87 Fed. Reg. 60186-87 (Oct. 4, 2022); Request for Information Regarding Mortgage Refinances and Forbearances, 87 Fed. Reg. 58487-92 (Sept. 27, 2022).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Financing Lower-Priced Homes: Small Mortgage Loans” (2022), https://www.huduser.gov/portal/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Financing-Lower-Priced-Homes-Small-Mortgage-Loans.pdf.

- S. Zainulbhai et al., “The Lending Hole at the Bottom of the Homeownership Market” (New America, 2021), https://www.newamerica.org/future-land-housing/reports/the-lending-hole-at-the-bottom-of-the-homeownership-market/; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Financing Lower-Priced Homes”; A. McCargo et al., “Small-Dollar Mortgages for Single-Family Residential Properties” (Urban Institute, 2018), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/small-dollar-mortgages-single-family-residential-properties; E. Goldstein and K. DeMaria, “Small-Dollar Mortgage Lending in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware” (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2022), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/community-development/credit-and-capital/small-dollar-mortgage-lending-in-pennsylvania-new-jersey-and-delaware; L. Goodman, B. Bai, and W. Li, “Real Denial Rates: A Better Way to Look at Who Is Receiving Mortgage Credit” (working paper, Urban Institute, 2018), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98823/real_denial_rates_1.pdf; A. McCargo, B. Bai, and S. Strochak, “Small-Dollar Mortgages: A Loan Performance Analysis” (Urban Institute, 2019), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99906/ small_dollar_mortgages_a_loan_performance_analysis_2.pdf.

- Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, 2018-2021, https://ffiec.cfpb.gov/data-browser/; Zillow Group Inc., Zillow Transaction and Assessment Database, 2018-21, https://www.zillow.com/research/ztrax/. This analysis uses data on mortgage transactions from the HMDA database, the most comprehensive source of information on mortgage lending in the United States. Mortgage lenders report application-level information directly to the CFPB, which compiles and republishes the data for public use. Data on home sales was provided by Zillow through Zillow’s Transaction and Assessment Database (ZTRAX). More information on accessing the data can be found at https://www.zillow.com/research/ztrax/. The results and opinions are those of the authors and do not reflect the position of Zillow Group.

- Bankrate, “Nearly Two-Thirds Say Affordability Factors Are Holding Them Back From Homeownership” (Bankrate.com, 2022), https://www.bankrate.com/pdfs/pr/20220330-march-fsp.pdf.

- D. Sackett and K. Handel, The Tarrance Group, letter to Woodrow Wilson Center, “Key Findings From National Survey of Voters,” May 21, 2012, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/article/keyfindingsfromsurvey.pdf.

- Ibid.

- National Association of Realtors, “Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers” (2022), https://www.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/documents/2022-highlights-from-the-profile-of-home-buyers-and-sellers-report-11-03-2022_0.pdf.

- A. Acolin, L. Goodman, and S.M. Wachter, “Accessing Homeownership With Credit Constraints,” Housing Policy Debate 29, no. 1 (2019): 108-25, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10511482.2018.1452042?casa_token=5ZjHGNxo1VoAAAAA%3AtLKWk_xn7JT3Uz2G7T_zziEuPZa0NlarhJ-tGl6m83DgxB6rq-IYSU7eZNI9mIwBAFx5o7BGbulINcjA.

- N. Bourke, T. Roche, and C. Hatchett, “Homeowners With Risky Alternatives to Traditional Mortgages Eligible for COVID-19 Relief Money,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, Nov. 1, 2021, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2021/11/01/homeowners-with-risky-alternatives-to-traditional-mortgages-eligible-for-covid19-relief-money.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “CFPB Rules Establish Strong Protections for Homeowners Facing Foreclosure,” news release, Jan. 17, 2013, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-rules-establish-strong-protections-for-homeowners-facing-foreclosure/.

- Goldstein and DeMaria, “Small-Dollar Mortgage Lending in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware.”

- Zillow Group Inc., “Zillow Home Value Index (ZHVI),” 2000-22, https://www.zillow.com/research/data/.

- Some borrowers use small mortgages to purchase properties valued at more than $150,000, but Pew is primarily interested in expanding homeownership opportunities to underserved populations, so this analysis considers only low-cost properties.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “What Has Research Shown About Alternative Home Financing in the U.S.?” (2022), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/04/what-has-research-shown-about-alternative-home-financing-in-the-us.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Manufactured Housing Finance: New Insights From the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Data” (2021), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_manufactured-housing-finance-new-insights-hmda_report_2021-05.pdf.

- A. Carpenter, T. George, and L. Nelson, “The American Dream or Just an Illusion? Understanding Land Contract Trends in the Midwest Pre- and Post-Crisis” (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2019), 9, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media/imp/harvard_jchs_housing_tenure_symposium_carpenter_george_nelson.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “What Has Research Shown?”; National Consumer Law Center, “Summary of State Land Contract Statutes” (2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/white-papers/2022/02/less-than-half-of-states-have-laws-governing-land-contracts.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Millions of Americans Have Used Risky Financing Arrangements to Buy Homes” (2022), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/04/millions-of-americans-have-used-risky-financing-arrangements-to-buy-homes.

- H.K. Way, “Informal Homeownership in the United States and the Law,” Saint Louis University Public Law Review XXIX, no. 113 (2010): 113-92, https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/hway/informal-homeownership.pdf.

- Ibid.

- HMDA data for 2022 was not available at time of publication.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Millions of Americans Have Used Risky Financing Arrangements to Buy Homes.”

- National Association of Realtors, “Realtors Confidence Index Survey” (2022), https://cdn.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/documents/2022-09-realtors-confidence-index-10-20-2022.pdf; D. Anderson, “Share of Homes Bought With All Cash Hits Highest Level Since 2014,” Redfin, https://www.redfin.com/news/all-cash-home-purchases-fha-loans-october-2022/.

- T. Malone, “Single-Family Investor Activity Bounces Back in the First Quarter of 2022” (CoreLogic, 2022), https://www.corelogic.com/intelligence/single-family-investor-activity-bounces-back-in-the-first-quarter-of-2022/.

- Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances, 1989-2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf/dataviz/scf/table/#series:Transaction_Accounts;demographic:agecl;population:all;units:median. In 2019, the median balance in the checking and savings accounts of Americans younger than 35 was just $3,240; it jumps to $5,620 for accountholders ages 55 to 64.

- Ibid.

- S. Riley, A. Freeman, and J. Dorrance, “Alternatives to Mortgage Financing for Manufactured Housing” (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for Community Capital, 2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2022/03/alternatives-to-mortgage-financing-for-manufactured-housing.pdf.

- Malone, “Single-Family Investor Activity Bounces Back.”

- L. Goodman, J. Zhu, and B. Bai, “Overly Tight Credit Killed 1.1 Million Mortgages in 2015,” Urban Wire (blog), Urban Institute, Nov. 21, 2016, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/overly-tight-credit-killed-11-million-mortgages-2015.

- E. Dowdall et al., “Investor Home Purchases and the Rising Threat to Owners and Renters: Tales From 3 Cities” (Nowak Metro Finance Lab, 2022), https://drexel.edu/~/media/Files/nowak-lab/220923_InvestorHomePurchases_Final.ashx?la=en.

- Federal Reserve Board, Survey of Consumer Finances, 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm.

- Ibid.

- ATTOM Data Solutions, “Owning a Home More Affordable Than Renting in Nearly Two Thirds of U.S. Housing Markets,” Jan 7, 2021, https://www.attomdata.com/news/market-trends/home-sales-prices/attom-data-solutions-2021-rental-affordability-report/.

- D. Olick, “Here’s Where Owning a Home Is Cheaper Than Renting One,” CNBC, Feb. 7, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/07/where-owning-a-home-is-cheaper-than-renting-one.html.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “What Has Research Shown?,” 5.

- Goodman, Bai, and Li, “Real Denial Rates.”

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Request for Information: Mortgage Refinances and Forbearances,” Sept. 27, 2022, https://www.regulations.gov/document/CFPB-2022-0059-0001/comment; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Request for Information Regarding Small Mortgage Lending,” Oct. 4, 2022, https://www.regulations.gov/docket/HUD-2022-0076/comments.

- Alan S. Kaplinsky et al., “DOJ Fair Lending Focus Continues in Settlement of Case Challenging Lender’s Minimum Loan Amount Policy by the Consumer Financial Services and Mortgage Banking Groups,” Casetext, https://casetext.com/analysis/doj-fair-lending-focus-continues-in-settlement-of-case-challenging-lenders-minimum-loan-amount-policy-by-the-consumer-financial-services-and-mortgage-banking-groups. Although some lenders might not originate small mortgages mainly because they operate primarily in high-cost areas, others may require minimum loan sizes, either formally or informally, that exclude low-cost borrowers. The U.S. Department of Justice ruled in 2012 that setting minimum loan sizes of $400,000 or more violates the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, but whether minimum thresholds of $150,000 are unlawful remains unclear.

- Mortgage Bankers Association, “Chart of the Week—July 23, 2021 Retail Production Channel: Cost to Originate ($ Per Closed Loan),” July 23, 2021, https://newslink.mba.org/mba-newslinks/2021/july/mba-newslink-monday-july-26-2021/mba-chart-of-the-week-july-23-2021-retail-production-channel-cost-to-originate/; Mortgage Bankers Association, “MBA: 2022 IMB Production Profits Fall to Series Low,” MBA Newslink, https://newslink.mba.org/mba-newslinks/2023/april/mba-2022-imb-production-profits-fall-to-series-low/.

- K. Graham, “Mortgage Origination Fee: The Inside Scoop,” Rocket Mortgage LLC, https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/mortgage-origination-fee; M. Crace, “Closing Costs: What Are They, and How Much Will You Pay?,” Rocket Mortgage LLC, https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/closing-costs.

- Zillow Inc., “How Is Your Loan Officer Paid?,” https://www.zillow.com/blog/how-is-your-loan-officer-paid-500/.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Housing Survey (2021), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data/2021/ahs-2021-public-use-file--puf-/ahs-2021-national-public-use-file--puf-.html.

- E. Divringi, “Updated Estimates of Home Repairs Needs and Costs and Spotlight on Weatherization Assistance” (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2023), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/community-development/housing-and-neighborhoods/updated-estimates-of-home-repairs-needs-and-costs-and-spotlight-on-weatherization-assistance.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “MBA Response to FHA RFI Regarding Small Mortgage Lending,” Dec. 5, 2022, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/HUD-2022-0076-0025; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “New America and CSEM Response to Docket No FR-6342-N-01 on Small Mortgage Lending,” Dec. 5, 2022, https://www.regulations.gov/comment/HUD-2022-0076-0015.

- To qualify, loans must meet three criteria: They cannot have negative amortization, interest-only payments, or balloon payments; the total points and fees charged cannot exceed 3% of the loan amount; and the term must be 30 years or less. They also must satisfy at least one of the following three criteria: The borrower’s total monthly debt-to-income ratio must be 43% or less; the loan must be eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac or insured by the FHA, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or U.S. Department of Agriculture; or the loan must be originated by insured depositories with total assets of less than $10 billion, but only if the mortgage is held in portfolio.

- F. D’Acunto and A.G. Rossi, “Regressive Mortgage Credit Redistribution in the Post-Crisis Era,” The Review of Financial Studies 35, no. 1 (2022): 482-525, https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article-abstract/35/1/482/6136188?redirectedFrom=fulltext; Freddie Mac, “Cost to Originate Study: How Digital Offerings Impact Loan Production Costs” (2021), https://sf.freddiemac.com/content/_assets/resources/pdf/report/cost-to-originate.pdf; T. Hogan, “Costs of Compliance With the Dodd-Frank Act” (Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, 2019), https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/dodd-frank-costs-compliance.

- K. Berry, “Fed’s Rate Hikes Are Tanking the Mortgage Market,” American Banker, Oct. 24, 2022, https://www.americanbanker.com/news/feds-rate-hikes-are-tanking-the-mortgage-market.

- Mortgage Bankers Association, “MBA Members Urge Bureau to Change Loan Originator Compensation Rule,” MBA Newslink, Oct. 24, 2018, https://newslink.mba.org/mba-newslinks/2018/october/mba-newslink-wednesday-10-24-18/mba-members-urge-bureau-to-change-loan-originator-compensation-rule/.

- Y. Benzarti, “Playing Hide and Seek: How Lenders Respond to Borrower Protection,” The Review of Economics and Statistics (2022): 1-25, https://direct.mit.edu/rest/article-abstract/doi/10.1162/rest_a_01167/109257/Playing-Hide-and-Seek-How-Lenders-Respond-to?redirectedFrom=fulltext; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Manufactured Housing Finance,” 25-27.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Request for Information: Mortgage Refinances and Forbearances.”

- Federal Housing Finance Agency, “FHFA Announces Targeted Pricing Changes to Enterprise Pricing Framework,” news release, Oct. 24, 2022, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Announces-Targeted-Pricing-Changes-to-Enterprise-Pricing-Framework.aspx. G-fees are based on the individual mortgage’s product type and credit risk attributes and help Fannie and Freddie cover administrative costs and credit losses from borrower defaults. However, these fees also increase loan origination costs.

- Americans for Financial Reform, “Joint Letter: FHFA RFI on PACE Loans,” March 16, 2020, https://ourfinancialsecurity.org/2020/03/joint-letter-fhfa-rfi-pace-loans/; G. Kromrei, “Industry to Congress: G-Fees Aren’t Your ‘Piggybank,’” HousingWire, July 23, 2021, https://www.housingwire.com/articles/industry-to-congress-g-fees-arent-your-piggybank/; L. Goodman et al., “Guarantee Fees—an Art, Not a Science” (Urban Institute, 2014), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22841/413202-Guarantee-Fees-An-Art-Not-a-Science.PDF.

- Federal Housing Finance Agency, “FHFA Announces Two Measures Advancing Housing Sustainability and Affordability,” news release, Oct. 18, 2021, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Announces-Two-Measures-Advancing-Housing-Sustainability-and-Affordability.aspx.

- S. Lee, “How Mortgage, Housing Industries Tackled Affordability in 2022,” National Mortgage News, Dec. 29, 2022, https://www.nationalmortgagenews.com/list/how-mortgage-housing-industries-tackled-affordability-in-2022; Wells Fargo, “Wells Fargo Announces Strategic Direction for Home Lending: A Smaller, Less Complex Business Focused on Bank Customers and Minority Communities,” news release, Jan. 10, 2023, https://newsroom.wf.com/English/news-releases/news-release-details/2023/Wells-Fargo-Announces-Strategic-Direction-for-Home-Lending-A-Smaller-Less-Complex-Business-Focused-on-Bank-Customers-and-Minority-Communities/default.aspx.

- A. McCargo et al., “The MicroMortgage Marketplace Demonstration Project: Building a Framework for Viable Small-Dollar Mortgage Lending” (Urban Institute, 2020), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/micromortgage-marketplace-demonstration-project; Hurry Home, “A New Way to Be a Homeowner,” https://www.hurryhome.io/.

- Federal Housing Finance Agency, “FHFA Announces Inaugural Housing Finance TechSprint,” news release, April 4, 2023, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Announces-Inaugural-Housing-Finance-TechSprint.aspx.

- L. Goodman, J. Zhu, and T. George, “Four Million Mortgage Loans Missing from 2009 to 2013 Due to Tight Credit Standards,” Urban Wire (blog), Urban Institute, April 2, 2015, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/four-million-mortgage-loans-missing-2009-2013-due-tight-credit-standards.

- Fannie Mae, “Fannie Mae Introduces New Underwriting Innovation to Help More Renters Become Homeowners,” news release, Aug. 11, 2021, https://www.fanniemae.com/newsroom/fannie-mae-news/fannie-mae-introduces-new-underwriting-innovation-help-more-renters-become-homeowners; Freddie Mac, “Freddie Mac Takes Further Action to Help Renters Achieve Homeownership,” news release, June 29, 2022, https://freddiemac.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/freddie-mac-takes-further-action-help-renters-achieve; Freddie Mac, “Freddie Mac Announces Underwriting Innovation to Help Lenders Qualify More Borrowers for a Mortgage,” news release, Oct. 17, 2022, https://freddiemac.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/freddie-mac-announces-underwriting-innovation-help-lenders; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Federal Housing Administration Expands Access to Homeownership for First-Time Homebuyers Who Have Positive Rental History,” news release, Sept. 27, 2022, https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/HUD_No_22_187.

America’s Overdose Crisis

Sign up for our five-email course explaining the overdose crisis in America, the state of treatment access, and ways to improve care

Sign up

Pathways to Homeownership: Housing in America

Millions Using Risky Financing Arrangements to Buy Homes

Homebuyers Using Alternative Financing Face Challenges