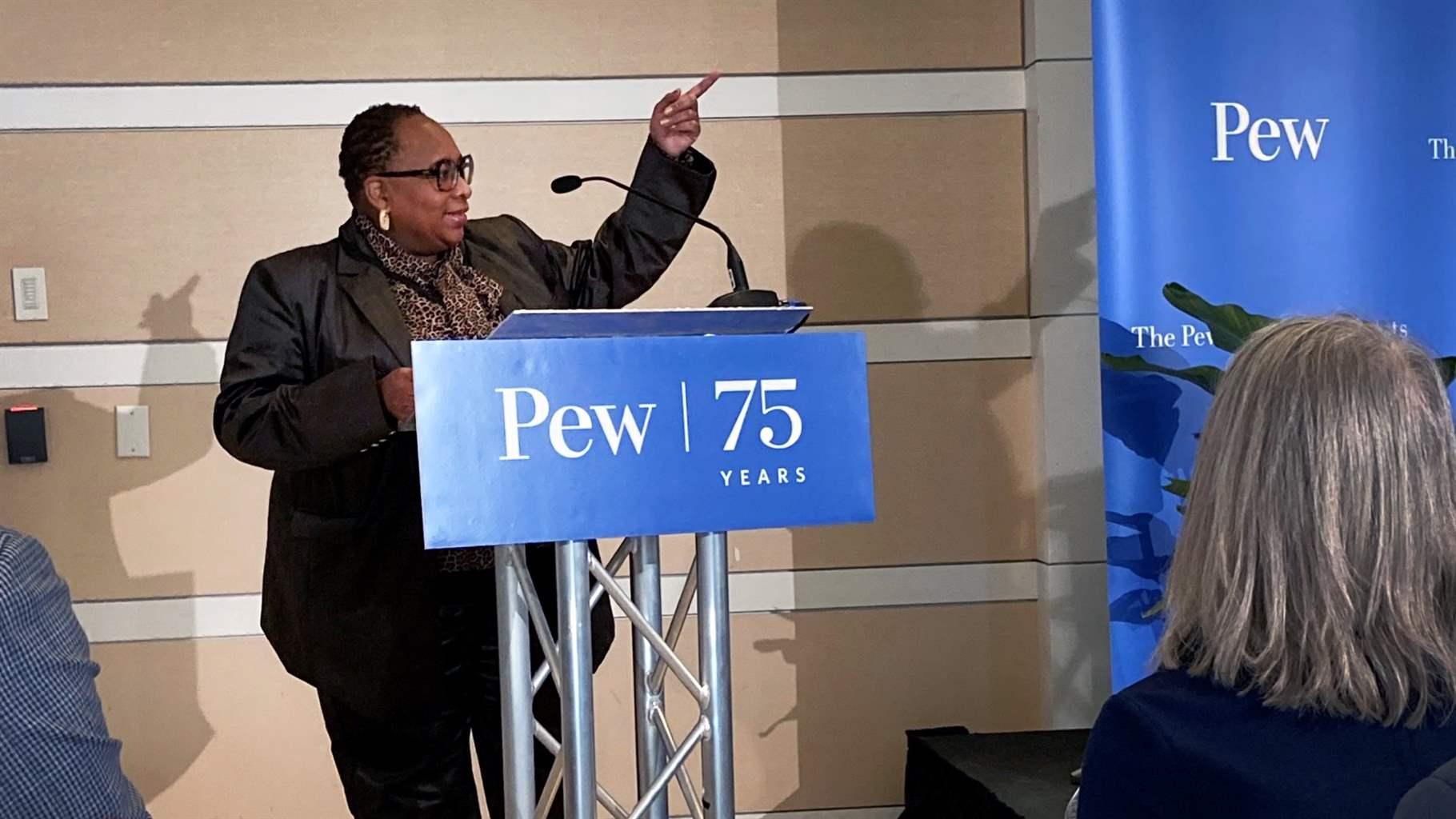

Meet Donna Frisby-Greenwood, Who Leads Pew’s Philadelphia Work

New senior vice president with deep roots in the city is driven to help its residents thrive

Donna Frisby-Greenwood joined The Pew Charitable Trusts as vice president of Philadelphia programs in October 2022, and in March 2023 became senior vice president of Philadelphia and scientific advancement. In this role, she leads all of Pew’s grantmaking, research, and policy work throughout the Philadelphia region; the organization’s support for programs that build religious tolerance throughout the United States; and support for communities of biomedical and marine scholars around the world.

We talked with Frisby-Greenwood to learn more about her strong ties to Philadelphia, her career, and her vision for Pew’s continued impact on the city and region, as well as how her religion and scientific advancement work intersects with Pew’s Philadelphia portfolio.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your family has a rich history in Philadelphia. Could you talk a little bit about that?

A: I’m a third-generation Philadelphian on my father’s side and second generation on my mother’s side. My paternal grandparents raised their six children in the city’s Germantown neighborhood. My maternal grandparents moved to Philadelphia from the South in 1920; my maternal grandfather was a longshoreman on the Delaware River, and he and my grandmother raised my mother and her nine older siblings in what is now Queen Village. They attended Mother Bethel AME Church, where some of our family members still belong.

My family took great pride in owning their own homes and paving the way for others. In 1946, one of my uncles was one of the first five Black drivers hired by SEPTA, the city’s mass transit agency, and another uncle, a doctor with a family medicine practice in Tioga, was one of the first investors in the Rev. Leon Sullivan’s Progress Plaza, which in 1968 became the first African American-owned shopping center in the U.S.

My dad, while managing procurement at the General Services Administration from his office at Ninth and Market, created and authored what became the federal government’s minority set-aside program in the early 1970s. Also in the ’70s, one of my uncles established and served as dean for the Philadelphia campus of Antioch University, which was the first school in the country to give working adults college credit for their lived experience.

In addition, one of my aunts was the first Black keypunch operator hired by the city of Philadelphia in the 1950s, and my great-aunt was the first Black teacher hired at Fels Junior High School in 1954; when I taught there as a substitute in the late 1980s, I was greeted by her photo and plaque at the entrance to the building, which gave me great pride.

Q: And what about your own history with the city and the region?

A: I was born in New York City, but my family moved to Nicetown/Tioga in North Philadelphia when I was 2. When I was 4, we moved to LaMott, a historic section of Cheltenham Township in the Montgomery County suburbs, but I could still walk to visit family in West Oak Lane and take short car or bus rides to see family in Mt. Airy and Germantown. I grew up attending Sixers and Eagles games, as well as plays at Freedom Theater, where I later studied dance in the summer. In college, I worked at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Marine Design Center in the U.S. Custom House. After undergrad, I returned home to Philadelphia, where I taught at Ellwood Elementary and Olney High School. As a young adult, I purchased my first home and raised my family in the Northern Liberties section of the city; today, I live just outside the city in Wyncote and work in Center City, which gives me a strong perspective on both the city and its suburbs.

Q: How do you think this history has influenced your dedication to supporting communities and residents in the region?

A: When I was growing up, I always felt safe. I could jump on the subway, bus, or trolley and safely get where I was going. My family members and their neighbors owned their homes, and people took a lot of pride in their blocks and neighborhoods. But today, homeownership is down, safety has become a big issue, and far too many people lack wages that allow them to properly care for themselves and their families. I want to see my city and its residents thrive, where everyone feels safe and healthy, and where everyone has the opportunity to earn family-sustaining wages and engage in civic and cultural activities.

Q: Since joining Pew a year ago, you’ve taken a lot of time to meet with partner organizations, individual and institutional stakeholders, and Philadelphia-area residents. What have you learned from those conversations?

A: I’ve really enjoyed my time listening to people from all across the city and region—and as people who live here know, Philadelphians will tell you what’s on their minds. What really stood out to me is how much people appreciate Pew’s work—whether it’s the City Council staffer who reads our research reports, the philanthropic partner who can collaborate to make the city even more vibrant, or the grantee who looks for our support to effect positive change for Philadelphians with complex needs.

I’ve also found a lack of clarity about what Pew does and how we do it. Pew has been a steadfast supporter of Philadelphia and the region since 1948, so I’ve made it a priority to make myself and Pew’s work more accessible and transparent. This includes plans to share how the breadth and depth of Pew’s work in Philadelphia—and at the state and national levels—is benefiting our area and its residents.

Q: What’s something that people may find surprising about Pew’s presence in Philadelphia?

A: That Pew’s Philadelphia staff, about 75 employees, fills an entire floor in Commerce Square. The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage also has an office on Walnut Street with about 15 full-time staff members. I think Philadelphians—and even our partners—don’t realize just how large our presence is in the city. And our offices are filled with Philadelphians—from people like me who have a long history here to recent transplants—who all share a commitment, passion, and drive to make Philadelphia a place where all residents can thrive. I also think people don’t realize that Pew’s state, national, and international work has an impact on Philadelphians as well, including work in areas such as criminal justice reform, treatment access for substance use disorders, and even environmental issues such as flood preparedness.

Q: Before coming to Pew, you were the Philadelphia program director for the Knight Foundation—and most recently, the president and CEO of the Fund for the School District of Philadelphia. How did those experiences prepare you for your current role?

A: When I directed the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation’s grantmaking in Philadelphia from 2010 to 2015, I discovered how early-stage support could really be a catalyst for organizations and their projects. At the Fund for the School District, I learned the importance of public-private partnerships in tackling large, complex problems, as well as how to serve as a convener who brings stakeholders together to align priorities and find solutions to critical challenges.

Q: As a teacher, and later in your role at the school district, your emphasis was on children and education. What’s the relationship between that experience and your work at Pew?

A: While much of my career has focused on children and youth, the pandemic made clear to me that we also need to provide support, guidance, and resources for their parents, caregivers, and communities if we want to make the biggest impact on our children’s life trajectories. At Pew, I’m able to expand my impact on Philadelphia and its residents, including its children, by working to support communities and families—which includes helping local government better serve their needs.

Q: Pew plays a varied role in the Philadelphia region: funder, convener, partner, researcher, and policy expert. How do you thread all that work together?

A: All that work fits with Pew’s goal of supporting the Philadelphia region, its communities, and its residents. We bring together officials and experts to discuss policy issues and potential solutions that affect Philadelphians and their well-being, while providing data that helps local and state leaders make tough policy decisions. We provide grants that help to lift up our neighbors who are facing challenges rooted in poverty, while also funding art and artists who reflect the diversity, complexity, and vibrancy of our city and region. And, of course, we collaborate with private and public partners to fund projects that will enhance quality of life for everyone.

Q: Can you give an example or two of projects you’ve been excited to be a part of so far?

A: Sure. In April, I got to help launch Pew’s annual “State of the City” report, which highlights important data about Philadelphia and puts it into context so that everyone can understand the opportunities and challenges we Philadelphians collectively face. The report shows some progress as Philadelphia and the rest of the world began to emerge from the pandemic, but there are still significant issues that need to be addressed: The city has added more jobs, but not enough family-sustaining ones; major crimes have risen to the highest levels since 2006; and, for many families, affordable housing continues to be out of reach. For me, being part of the launch was a full-circle moment because of how much I used this report in my past positions.

In addition, I recently joined the city, the state, the William Penn Foundation, the Knight Foundation, and other funders to break ground on the Park at Penn’s Landing, a long-awaited connection between Center City and the Delaware River waterfront that’s a 4-acre public park above I-95. I was at the Knight Foundation when it made a commitment to this project, so attending the groundbreaking as a representative of Pew was another full-circle moment for me.

Q: Any others?

A: Pew’s health and human services grantees are assisting communities and residents facing complex challenges; most recently, we gave $6.55 million to five local organizations working to make mental and behavioral health services more accessible to children and teens in underserved communities. And through our Philadelphia research and policy work, we’ve been convening public, private, and philanthropic partners to create a roadmap for jobs and economic development, and we launched our Emerging Leaders Corps program to help rising leaders from a range of sectors learn to use data to inform decision-making—which takes me back to my roots of identifying, training, and resourcing the next generation of Philadelphia leaders.

Q: You mentioned the challenges facing the region. How is Pew best positioned to help?

A: Pew has been supporting Philadelphia and the surrounding region for 75 years—since the organization was established in 1948 in Center City—and we’ve always made it a priority to adjust and evolve to meet the changing needs of our society and hometown.

As we contemplate Philadelphia’s current challenges and opportunities, we’re looking to take a more cohesive approach to Pew’s local work—coordinating our extensive networks and convening ability, research, grantmaking, technical assistance, and policy recommendations so that we can address important issues using a more holistic approach. An example might be around workforce issues and the need for more middle-wage jobs: We can provide data and analysis so that policymakers are educated on the issue; fund critical training and other programs in the neighborhoods that need them most; fund arts and culture projects that shed light on the issues or uplift particular communities; and lend our local, state, and national policy expertise to make recommendations that will spur equitable economic development.

While neither Pew nor any other single entity can fix many of Philadelphia’s issues alone, what we can do is be a strong partner by ensuring the work we undertake and support serves our communities’ greatest needs, so that all residents can feel safe and mentally and physically healthy, have pathways to economic stability and advancement, and have equitable access to civic and cultural enrichment.

Q: You noted that one of Pew’s roles in the region is to provide policymakers with data and analysis. In January, there’ll be a new mayor, new City Council president, and several new council members. How do you anticipate working with them?

A: As new policymakers take office in 2024, we’ll seek to leverage our strengths. For one, we’re already preparing an Accelerator program for new incoming officials and their staffs, to help them learn about equitable budget planning from Pew and other experts. We’re also continuing to research important issues like housing, immigration, jobs, and the economy—and poll Philadelphians on their feelings about the city—to help local leaders make data-informed decisions.

Q: How does your work with Pew’s religion program and scientific advancement portfolio intersect with your work in Philadelphia?

A: These three portfolios are somewhat distinct lines of work, but there are some common threads. For one, the Philadelphia, religion, and scientific advancement portfolios represent all of Pew’s grantmaking programs. And, like our Philadelphia work, those programs focus on building thriving communities. Through the religion program, we fund projects that aim to build religious tolerance in the United States, and through our scientific advancement portfolio, we fund biomedical and marine research while bringing our grantees from around the world together to learn from, and collaborate with, one another to solve some of the most complex scientific problems in their fields. In addition, one of those marine research programs, the Lenfest Ocean Program, was established as a partnership between Pew and the late Philadelphia philanthropist H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest.

Q: What’s your vision for Pew’s work in Philadelphia?

A: I’m still in the process of determining that. I plan to use the knowledge gained from meeting with numerous stakeholder groups—as well as my Pew colleagues who are experts in their fields—to examine ways we can make an even greater impact in our hometown by using the more collaborative and holistic approach I mentioned earlier. I hope to share more in the coming months.