How States Provide Health Benefits to Retired Workers

© Getty Images

© Getty ImagesIn 2013, states spent approximately $18.4 billion on OPEB liabilities, slightly lower than overall state spending on premiums for active state employees and much lower than states’ share of Medicaid, their largest health care expenditure.

A recent issue brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that the share of Medicare-eligible retirees who have employer-sponsored supplemental insurance is at a 25-year low, measuring between 16 and 25 percent depending on the national survey used. Rising health care costs, changes in accounting standards for reporting the cost of retiree health benefits, competition from overseas firms and small startup companies, and the addition of prescription drug coverage to the Medicare program have all contributed to this drop in private sector retiree health benefits. However, the public sector—specifically, state government—has not followed the national trend.

Although states have experienced many of the same accounting and marketplace changes that caused private employers to phase out retiree health coverage, a recent report from the State Health Care Spending Project, a collaboration of The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, found that every state except Idaho offers newly hired public workers access to at least some retiree health care coverage as part of their benefits package.

States periodically review their retiree health insurance programs, weighing factors such as whether large current and future costs of coverage will become unsustainable liabilities. National developments, including implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and changes to the Medicare program, also affect states’ decisions, as do labor negotiations with state employees. But states—in their role as employers—are also mindful that the promise of future health care benefits is an asset that helps attract and retain talented workers.

Large liabilities

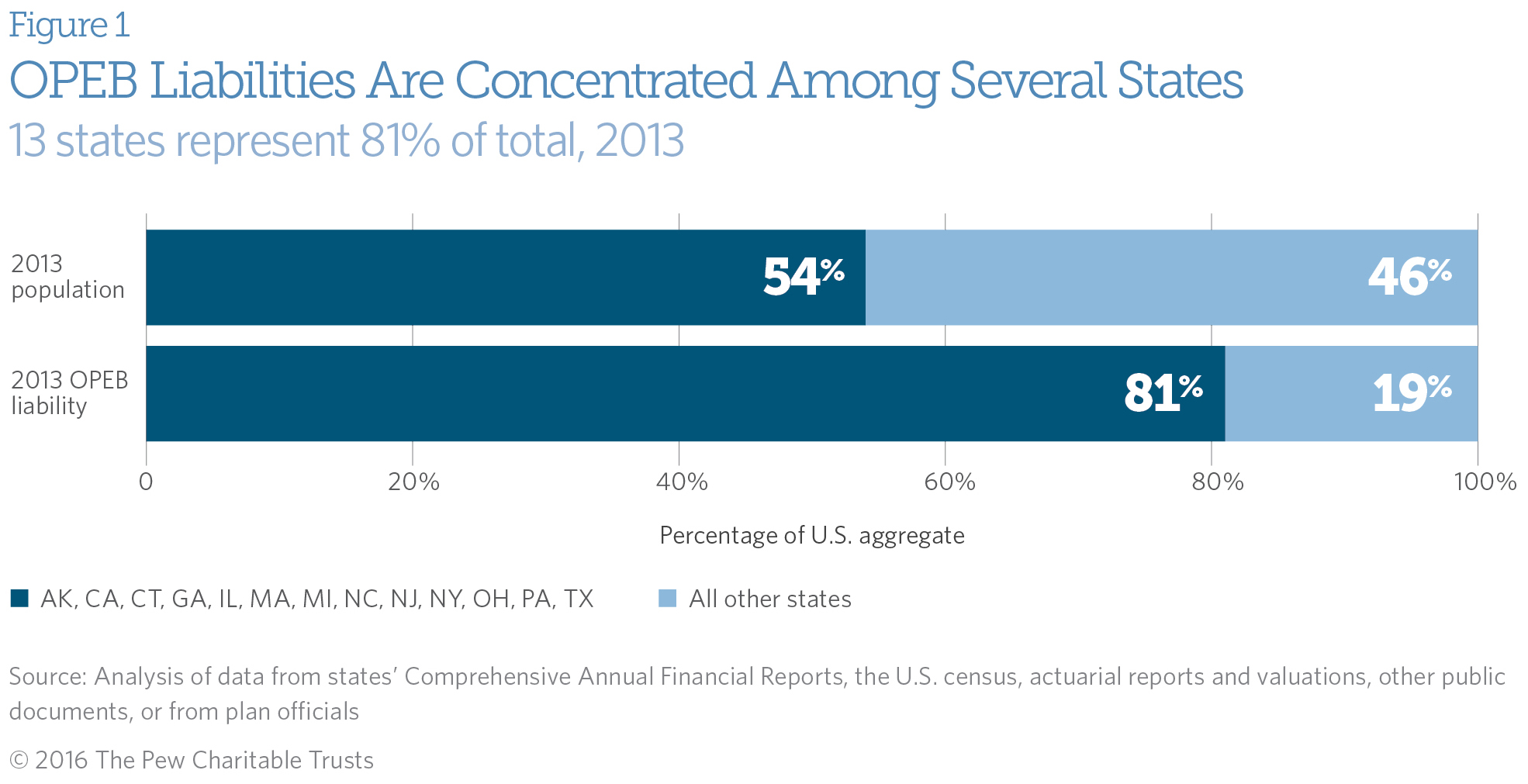

The Pew/MacArthur report finds that in 2013, state liabilities for retiree benefits other than pensions—known as other post-employment benefits (OPEB) liabilities—totaled $627 billion. But these liabilities were not distributed equally among the 50 states. As shown in Figure 1, 13 states, which represented about half of the U.S. population in 2013, accounted for 81 percent of the total OPEB liabilities.

In 2013, states spent approximately $18.4 billion on OPEB liabilities, slightly lower than overall state spending on premiums for active (current) state employees and much lower than states’ share of Medicaid, their largest health care expenditure. In particular, this number reflects how much states paid in 2013 for health insurance and other relatively inexpensive nonpension benefits (dental, life insurance) for current retirees and can also include money set aside to pre-fund liabilities—which some states do to lower their long-term financial obligations.

Provisions of state retiree health insurance plans

Although states have largely continued to offer retiree health insurance coverage to their employees, many have adjusted benefits to rein in future obligations and take advantage of cost-saving opportunities afforded by legislation such as the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) and the ACA (discussed below). Changes to benefit plans can take several forms, including adjusting eligibility requirements, contribution-to-premium strategies, and plan choice. States can also decide whether to continue offering coverage to early retirees who are not yet eligible for Medicare, Medicare-eligible retirees, both, or neither. All of these choices shape current costs and future liabilities.

Early retirees and Medicare-eligible retirees

Forty-seven states offer coverage, or access to coverage, to help reduce the cost-sharing burden Medicare-eligible retirees would otherwise face under the federal program—and for which other Medicare beneficiaries often purchase supplemental or Medigap insurance.

In 49 states, coverage or access to coverage is offered to early retirees. Before implementation of the ACA, retirees without such coverage would have had to purchase a plan on the individual market before qualifying for Medicare and could have been denied coverage or charged a higher premium because of a pre-existing condition.

The ACA’s “guaranteed issue” provision eliminated the problem of denial of coverage. And, even in the absence of a state contribution to the premium, state health insurance coverage remains valuable to early retirees. Premiums are lower than on the individual market, a result of participation in a large group insurance pool that has considerable negotiating power with insurers. Early retirees, with access to the same health insurance and total premium offered to their states’ active employees, also benefit from an implicit subsidy, because these early retirees tend to have higher health care costs, on average, than do active employees. States that offer the same premium to early retirees and active employees create what is known as a “blended” premium, with active employees paying a higher premium and early retirees a lower one than they would otherwise.

State premium contributions

How states set their contributions to health insurance premiums vary. On one end, some states—including Oregon, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin—allow retirees to purchase coverage through the state much like active employees but offer no contribution to the premiums for either their early or Medicare-eligible retirees. In others, such as Illinois, Maine, and New Hampshire, contributions may cover up to 100 percent of the premium for retirees who have worked for the state the required number of years.

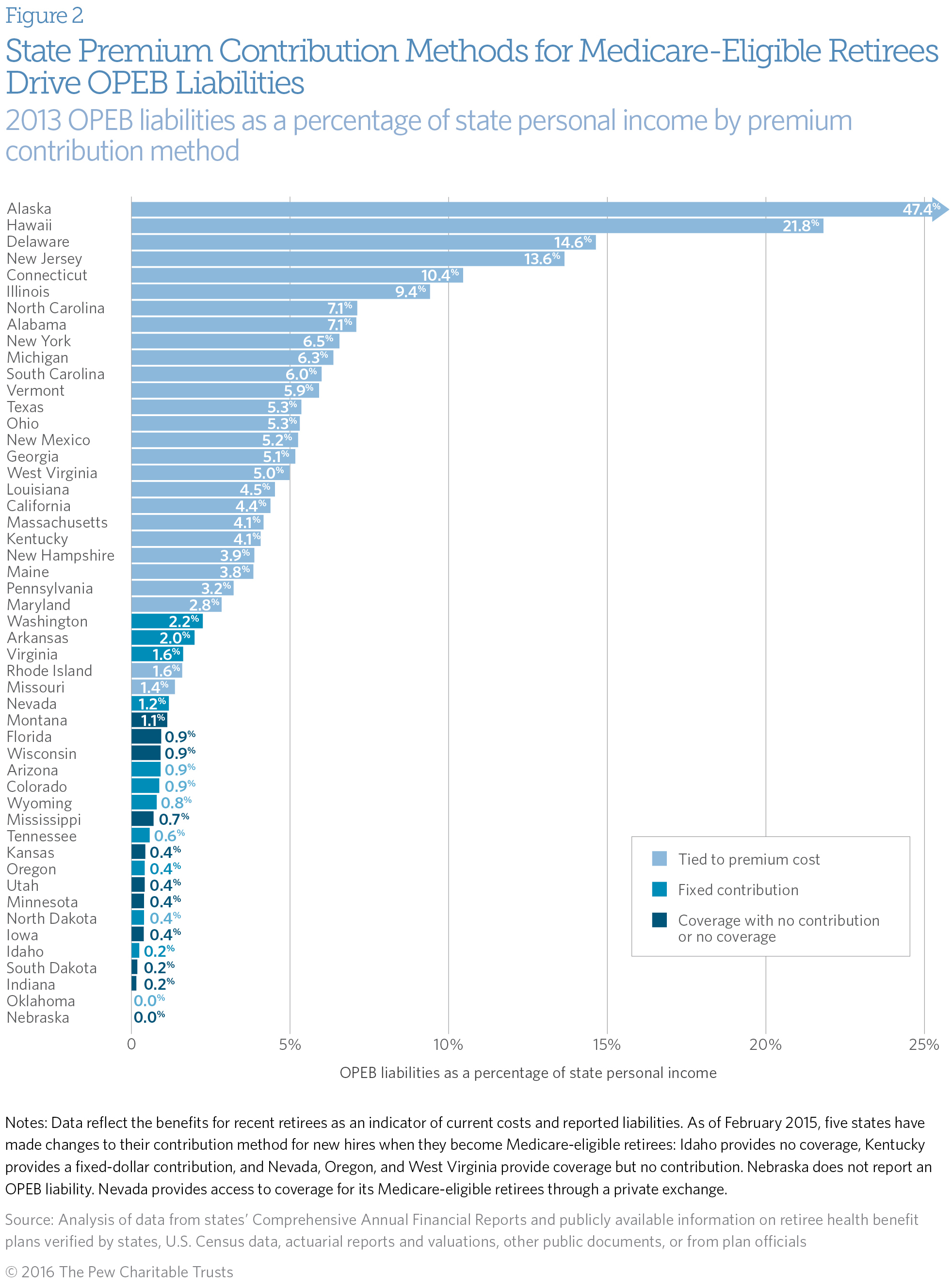

When states do contribute to premiums, the contribution method is closely connected to the extent of their OPEB liabilities. Twenty-seven states tie their retiree premium contribution for current Medicare-eligible retirees to the actual cost of health insurance each year and therefore have less control over how much their contribution varies from year to year. If premiums increase, these states must increase their spending, decrease their contribution rate, or introduce lower-cost plans. Twelve states offer a fixed-dollar contribution toward their current Medicare-eligible retirees’ health premiums, with the retirees paying the difference between the contribution and the actual premium. Because they are shielded from health plan premium increases, states that structure their contributions in this manner tend to have more predictable costs from year to year. The remaining states make no contribution to the premium for these retirees or don’t offer coverage.

As shown in Figure 2, states that automatically increase their health insurance premium contribution when the total cost of the premium rises had higher OPEB liabilities, relative to the size of their economies in 2013, than states that paid a fixed amount toward such premiums.

Changes to plan administration and offerings

As states have worked over the past decade to balance maintaining a competitive workforce with fiscal constraints, they have refined their plan provisions. For example, many states use a retiree’s age and/or years of service to determine eligibility for health coverage and/or premium contributions. Pew researchers analyzed changes made to these criteria since 2000 and found that more than a dozen states changed the minimum age eligibility requirement, minimum years of service requirement for coverage, or both. Moreover, states may apply these changes to newly hired workers, current retirees, or both. Depending on the group affected, these choices have implications for state liabilities in the future. For example, changes that only reduce benefits for newly hired workers will not reduce OPEB obligations until many years later.

States have also changed how they coordinate their benefits with the federal Medicare program, which can affect costs. Since Medicare Advantage (MA) plans were authorized as part of the 2003 MMA, 21 states have introduced them to provide health coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees. These plans cover benefits under Medicare Parts A and B (and often D) and reduce Medicare cost sharing, such as deductibles and coinsurance payments. In addition, they set an out-of-pocket maximum outlay for enrollees that traditional Medicare does not.

States benefit from offering MA plans because they are generally less expensive than individual wraparound plans, which provide coverage that is secondary to Medicare Parts A and B and may cover Medicare copays, coinsurance, and deductibles, as well as services not covered by Medicare. Some states offer MA plans instead of traditional Medicare and supplemental insurance; others offer MA plans along with them. But while states make key decisions regarding which insurance companies will participate and what MA plans will be available to retirees, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services regulates MA plans—so states have less control over the coverage these plans provide compared with wraparound plans.

In 2011, Nevada took another approach and contracted with a private exchange to administer retiree health benefits for its Medicare-eligible retirees. This method is sometimes also used in the private sector, where, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 7 percent of large firms offering retiree health benefits in 2015 did so through an exchange.

The exchange Nevada contracts with is run by a third-party administrator and offers retirees a choice among 85 participating carriers. Retirees, rather than the state, choose how they want to coordinate their benefits with the Medicare program, with the option to purchase Medigap, Medicare Advantage, and/or Part D plans. Instead of receiving a premium contribution, participants receive a contribution to a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) account, which they may use for plan premiums, including for Medicare Part B, or to pay for out-of-pocket medical expenses. The amount of the HRA contribution varies depending on an individual’s years of service.

According to Damon Haycock, executive officer for the Nevada Public Employees’ Benefits Program (PEBP), this approach offers advantages to retirees. In a presentation prepared for the 2016 national conference of the State and Local Government Benefits Association, he explained that retirees join a larger risk pool through the exchange than they would have under a state-run plan and therefore pay lower premiums. Haycock also cited the wide variety of benefit choices available to retirees, as well as retirees’ ability to choose how to use the state contribution to their HRA account. The PEBP also has reduced administrative burdens as a result of the switch.

However, he noted that the exchange can be confusing for retirees. Communication regarding benefits may come from multiple sources, such as PEBP, the exchange administrator, and the plan the retiree has joined. Research also suggests that having too many choices can cause beneficiaries to delay or avoid making decisions about health coverage, although a well-designed, easy-to-use website can reduce this drawback.

Nevada has realized significant reductions in its OPEB liability because of the switch (and a move to a high-deductible health plan for early retirees), approximately 45 percent in the first year of implementation. These savings may prompt other states to explore these methods of providing health coverage to their retirees as they continue to balance costs with their desire to include some level of benefits as part of their compensation programs.

Conclusion

With over half of Medicare beneficiaries supplementing their health care coverage, state-offered benefits continue to be valuable to retirees. Forty-nine states offer these benefits in some way, and many have explored options for reducing their future liabilities by changing plan provisions, offering Medicare Advantage plans, or modifying how benefits are administered. As state policymakers address challenges in providing retiree health care, this research is intended to help them better understand how their spending, long-term liabilities, and criteria for premium contributions and coverage eligibility compare with those of other states.

Maria Schiff directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ research on state health care spending, and Frances McGaffey is an associate working on Pew’s state and local fiscal health initiatives.