New Mexico National Monument, Like Most Others, Fuels Local Economy

Río Grande del Norte draws wide range of enthusiasts, supporting jobs and community

The Río Grande carves an 800 foot deep gorge along the base of Cerro Chiflo, and Ute Mountain.

© Stuart Wilde

Four years after its designation, the Río Grande del Norte National Monument in Taos County, New Mexico, is celebrated more than ever by sportsmen, tribal leaders, veterans, local and federal elected officials, the business community, and conservationists.

When proposed, the monument drew strong local support because it would protect sites that are sacred to Native Americans and provide essential wildlife habitat, clean water, and outstanding outdoor recreational opportunities. After more than two decades of public input and dialogue, the monument was established March 25, 2013, under the Antiquities Act.

Since its designation, its value has been shown in another important way: as an economic engine for the local community. This should not come as a surprise.

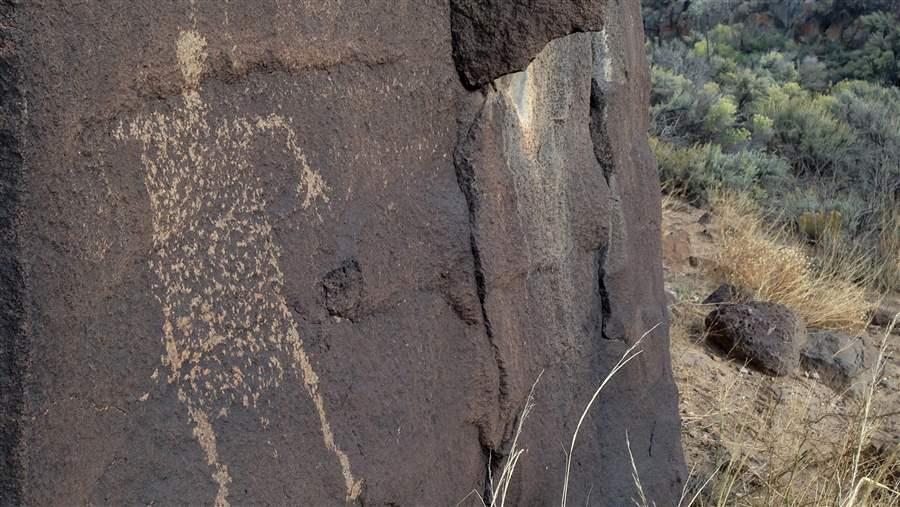

Río Grande del Norte is home to sacred cultural petroglyphs, tribal sites, and ruins.

© Stuart WildeFor starters, outdoor recreation in New Mexico, as in most of the country, is a growing and sustainable industry. The Outdoor Industry Association found that pursuits from hunting, fishing, and camping to mountain biking, skiing, and whitewater rafting generate $6.1 billion in consumer spending and 68,000 jobs annually across the state.

Rafters paddle on the Rio Grande. People also hike, bike, camp, fish, hunt, and ride horseback at the national monument.

© Bureau of Land Management

However, that is just one way in which protected public lands contribute to northern New Mexico’s economic growth. A recent study from Headwaters Economics found that rural counties in the West with higher shares of public lands enjoyed, on average, faster growth in population, employment, and personal income than counties with less federal land.

The study noted that Taos County, 57 percent of which is public land, recorded increases in population (82 percent), employment (194 percent), per capita income (101 percent), and total personal income (266 percent) between 1970 and 2015.

Designation of Río Grande del Norte bolstered that economic advance. After the monument’s first year, the Bureau of Land Management’s Taos Field Office reported a 40 percent increase in visitors to the area. The same year, the town of Taos enjoyed a 21 percent boost in tax revenue from stays in hotels, motels, and bed-and-breakfasts, and an 8.3 percent jump in gross receipts revenue in the accommodations and food service sector.

The Rio Grande enters New Mexico through a 200-foot-deep, 150-foot-wide gorge, then carves a chasm between 900-foot cliffs.

© Bureau of Land Management

In Taos County, the economic expansion is the result of people choosing to live, work, and raise their children in communities that are close to protected public lands. And as the population rises, community-oriented businesses such as grocery stores, hospitals, and locally owned shops and restaurants also emerge and grow.

“When more people than ever before visit our state and spend their hard-earned dollars in our small businesses,” Governor Susana Martinez (R) said, “that means more jobs and more money for our communities.”

The national monument is home to bighorn sheep, along with mule deer, pronghorn, otter, trout, and birds of prey.

© Bureau of Land Management

Even as Río Grande del Norte National Monument marks its fourth anniversary, some members of Congress are moving to undermine the bedrock law that allowed such designations—the 1906 Antiquities Act. Such a move could have grave consequences for millions of acres of public lands that tens of millions of Americans cherish. That’s why local communities, which see the many benefits of these monuments, should raise their voices in support of continued protection of our country’s awe-inspiring, sacred, and unique landscapes. We owe this to the communities that rely on these lands for their jobs, incomes, and well-being, and for future generations.

Mike Matz directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. public lands program, focusing on wilderness and national monument projects.