Natural Wonders

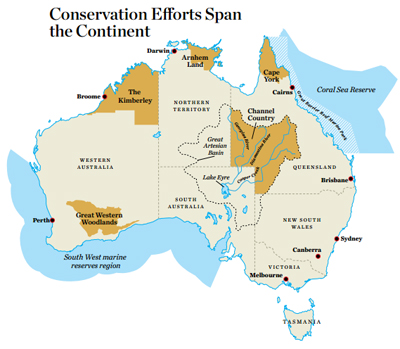

Conserving Australia's Treasure of Resources on Land and Sea

Water sloshes over the white hood of his truck as Angus Emmott plows through floodwaters running thick red with soil, talking all the while about this place that is his heritage and his treasure.

Water sloshes over the white hood of his truck as Angus Emmott plows through floodwaters running thick red with soil, talking all the while about this place that is his heritage and his treasure.

Hat brim snapped down against the sun, blue shirt unbuttoned in the heat, his foot stays hard on the gas pedal as he bounces across a swollen river that sat arid for a decade.

This is his place in the universe, a piece of Australia's western Queensland. His family has raised cattle here for almost a century in one of the most wondrous ecosystems in the world, and certainly one of the last of this scale to have largely escaped man's heavy hand.

“We're in a wonderful position,” he says. “We've got some of the last major dryland rivers anywhere in the world that are in great shape, and if we make the right decisions now we can keep them that way. But if we make the wrong decision once, we can lose them as well.”

Australia's vast and fragile ecosystems and the belief they could be protected against mounting outside pressures drew Pew to this continent, which spreads across almost 3 million square miles but has 10 million fewer people than urban Tokyo. Surrounding it are some of the world's most important waters, including the fabled Coral Sea. They are home to teeming species of aquatic life and create an island nation, isolating its ecosystems from the rest of the world.

“We have an opportunity here to get out ahead of the curve, to do conservation planning in advance, to set aside very large areas reserved for nature and to apply state-of-the-art management practices to protect the ecosystem,” said Steven Kallick, who leads Pew's campaign to preserve Canada's boreal forest and was dispatched five years ago to determine whether a similar effort could succeed Down Under.

“I was just blown away by the respect that the average people had for the ecological importance of Australia—a real basic love for their country,” he said. “There were a bunch of reasons that it looked like a very favorable place for us to work.”

Among them was that love of country, which has been translated into a political will to protect its natural resources, and a strong network of environmental groups eager to form coalitions to promote that cause.

At the same time, the threat to Australia's natural bounty was growing. There is an increasing demand for minerals from East Asian countries and overfishing was a mounting concern.

The people with the most knowledge about how to protect an area are those who live there. So Pew recruited Australians who could help lead the local efforts and guide the mission. There are now six campaigns spread across the country, as well as work being done to protect the ocean there.

“We decided that we were going to mount a 10-year effort to try to protect a series of very specific areas that we felt were unique in many ways, and where there was a real opportunity to get the job done,” said Joshua Reichert, managing director of the Pew Environment Group.

“We decided that we were going to mount a 10-year effort to try to protect a series of very specific areas that we felt were unique in many ways, and where there was a real opportunity to get the job done,” said Joshua Reichert, managing director of the Pew Environment Group.

Halfway through that effort, the successes have been mounting. The most recent came just this summer when the Australian government announced a historic decision to create the world's largest network of marine reserves that provide varying levels of protection. The move included a fully protected marine reserve for the Coral Sea that, at 194,000 square miles, is the second largest reserve of its kind on the planet.

Deeper in the red center of the Outback, other accomplishments have included helping the indigenous Aboriginal people return to the land that some had left and some had been forced to leave. They have been custodians of the land for thousands of years, and their involvement has been essential to controlling wildfires, invasive plants and feral animals that threaten unique species of animal life. With significant federal funding that flows through the Aboriginal groups, a network of indigenous rangers has been created to manage the land.

“Australia has been isolated for 30 million years,” said Barry Traill, an Australian who has directed Pew's Outback program since 2007. “It has been stable climatically and geologically. You compare that with North America, most of which was scraped clean by multiple ice ages. Places like Australia's Great Western Woodlands haven't had that sort of catastrophic sweep-clean of life, so things have been puttering along, evolving for millions of years, and because of that you get this great flowering of diversity.

“There are parts of the Outback, like the Arnhem Land, the Kimberley, the Great Western Woodlands and Cape York, that are sort of the jewels within the Outback, and that's where we focus,” Traill said, ticking off the places where Pew is at work.

Another jewel is the area that surrounds Angus Emmott's home in Noonbah Station, where the Vergemont Creek flows into the Thomson River in southwestern Queensland.

But the creek and river don't flow that often. For years on end, they sit empty. The landscape beside them fades from green to brown, the soil grows so dry that it cracks and some species cease to breed as they once did.

Then, on a schedule so erratic that the wet years are savored in memory much as an oenophile recalls Bordeaux's fabled vintages, the water comes in torrents when the rare hurricane strays south into the center of Australia.

“The Vergemont can be three miles wide overnight, it rises that quickly,” said Emmott, a board member of the Australian Floodplain Association, which works with Pew. For 10 years, the Channel Country sat bone-dry. Then in 2009, and for the next three years, the rains have come. Animals of every species—from the smallest of insects to fish and native animals—engage in a breeding bacchanalia that quickly fills the landscape with wildlife. Millions of water birds arrive to mate, so many that they collide like bumper cars as they paddle about in the billabong.

“Some of these water birds are pelicans from the south coast of Australia,” said Rupert Quinlan, who manages the Channel Country campaign for Pew. “No one has worked out how they actually know when these rivers flood.”

The whole Great Artesian Basin, almost one-sixth of Australia, drains down the Cooper, Georgina and Diamantina river systems into Lake Eyre, a vast salt lake that covers almost 3,700 square miles.

With Pew's help, unlikely alliances were formed to push back against mining and irrigation interests that wanted to use large amounts of water.

“We managed to get a coalition of Aboriginal folks, local mayors, ranch groups—a whole range of people who very rarely sit around the table and talk to each other,” said Quinlan. “During a three-year period, we managed to negotiate our way to a very extensive common ground.”

The results achieved by that Western Rivers Alliance: The Wild Rivers Act, which protects more than 15,000 square miles of watershed made up by the Georgina and Diamantina rivers and Cooper's Creek.

“It is,” Quinlan said simply, “the strongest water protection act in the world.”

The Serengeti of the Sea

The majestic turquoise water lapped against the boat's hull, dark shadows hinting at what lay below.

From more than half a mile down in the Coral Sea, a mountain that might sit comfortably among the Himalayas rises until it almost breaks the surface.

Descend through that water and the mountain wall sprouts massive soft coral, big sea fans and giant gorgonians. Then the sharks command attention: fifty-two species, 18 of them unique to these waters.

Thousands of other fish catch shafts of sunlight that glance off their spectacular colors. And then scores of barracuda, spinning in a silver circle like lions parading the center ring under the big top.

“It was magical. Probably the most amazing experience I've had underwater,” said Imogen Zethoven, Coral Sea campaign director for Pew's Global Ocean Legacy project. “These barracuda just kept getting closer and closer to us. We just kept hanging in the water staring at them, and they were as entranced by us as we were by them.”  Sixty miles beyond the border of the heralded Great Barrier Reef lies Osprey Reef, an iconic and pristine gem of the Coral Sea.

Sixty miles beyond the border of the heralded Great Barrier Reef lies Osprey Reef, an iconic and pristine gem of the Coral Sea.

Close to 400,000 square miles in all, the Coral Sea shares its waters with 25 species of whale, sometimes found in pods of up to 400, and five threatened turtle species. Where its reefs and undersea mountains break the water surface to form atolls and small islands, seabirds are found in abundance: terns, frigates and boobies among them.

After the thunder of a pivotal World War II battle receded, the Coral Sea quickly reverted to a natural state of evolution that has endured for thousands of years. That peace was punctured by longline fishing vessels whose baited hooks run for up to 30 miles, and by trawlers and charter boats carrying sport fishermen—potent political forces Down Under. As Pew set out to build a coalition to protect the Australian portion of the Coral Sea, the nation's affection for the Great Barrier Reef sitting beside it posed a surprising hurdle.

“It was difficult to create an identity for a body of water right next to the most cherished area in Australia and among the most admired in the world,” said Zethoven, who before joining Pew had worked to help designate one-third of the reef as a marine park. “Our challenge was to create the Coral Sea as its own iconic area.

“We realized,” she said, “that this is an underwater Serengeti. This is a place teeming with large migratory ocean fish such as mighty tunas, marlin and sharks, just as the Serengeti is home to an annual migration of wildebeests, zebras and gazelles.”

The Pew-led coalition—Protect Our Coral Sea—grew from four member organizations to 15 as momentum built, aided by a high-profile communications and outreach campaign and work with Australian media.

“The government received almost half a million public comments, and virtually all of them were supporting a higher level of protection,” Zethoven said.

In its June announcement, the government proposed to ban mining and oil exploration on more than 615,000 square miles of the Coral Sea. Longline fishing would be prohibited in almost two-thirds of that area and trawling would be limited to less than 1 percent.

“This is a massive step forward in ocean protection,” said Australia's environment minister, Tony Burke. “It's a bigger step forward than the globe has ever previously seen.”

Burke called the Coral Sea reserve “the jewel in the crown” of the largest network of marine reserves in the world, totaling 1.4 million square miles, and ringing the entire continent.

Before June's announcement, about 4 percent of Australia's territorial waters were protected sanctuary zones. The government plan now moving toward approval more than triples that to 13 percent.

“It's just a simple fact: No nation has ever put in place a system of marine protection on this scale,” said Michelle Grady, Pew's director for marine and Western Australia. “I know it sounds like heavy rhetoric, but it's not.”

A mysterious, amazing place

Cut a diagonal line through the continent from the Great Barrier Reef and its adjacent Coral Sea, and you land in the heart of the South West waters. They encompass more than a half million square miles of azure ocean, covering huge underwater mountain ranges and deep-sea canyons.

The 13,000-foot-deep Perth Canyon, about 25 miles out from the city for which it is named, ranks as perhaps the most stunning among them. Like the rest of the South West waters, it benefits from a quirk of nature. The prevailing ocean flow—equivalent to the Gulf Stream—runs from north to south along the coast. That pushes warm equatorial water toward Antarctica, supporting over the millennia the evolution of unique species.

“It is a mysterious and amazing place,” Grady said. “As the currents come through, they dip into this incredible canyon, pushing all the nutrients up off the sea floor and creating an oasis which results in a feeding frenzy of marine life.”

It is one of three places in Australia where endangered blue whales come to feed.

It also is a paradise for commercial and recreational fishing as have been most of the South West waters until catches in rock lobster, dhufish and other species began to decline. Once the government plan is completely in place, they will be protected.

“In the South West we were very careful to run a positive campaign,” Grady said. “Australians, before we started, mostly had the perception that the oceans are deep and uniform and that the important things tend to be just in tropical areas. So we needed to educate them to the fact that there are incredible, and mostly unique, marine life off Australia's southern shores.”

Ancient cultures and rainforests

When the massive maw of the largest hydraulic digging machine in the world works with a fleet of the largest dump trucks on earth, the burnt-orange soil that hides the vast iron ore fields of Western Australia vanishes rapidly.

The biggest of them all, at Cape Preston in the Pilbara of Western Australia, already has swallowed $8 billion in Chinese investment to slice open pits down to 600 feet below sea level, build a desalination plant and create a new port facility where ships can be loaded with 28 million tons of ore a year bound for steel plants in China.

The Cape Preston mine figures to be the largest yet, and among the biggest in the world. It is just one of many enormous open mines that have been dug across the landscape in the past several years as resource-hungry Asian interests train their sights on mineral-rich Australia.

“We are very concerned that some mines are now going more and more into sensitive areas such as the Kimberley coast,” Grady said.

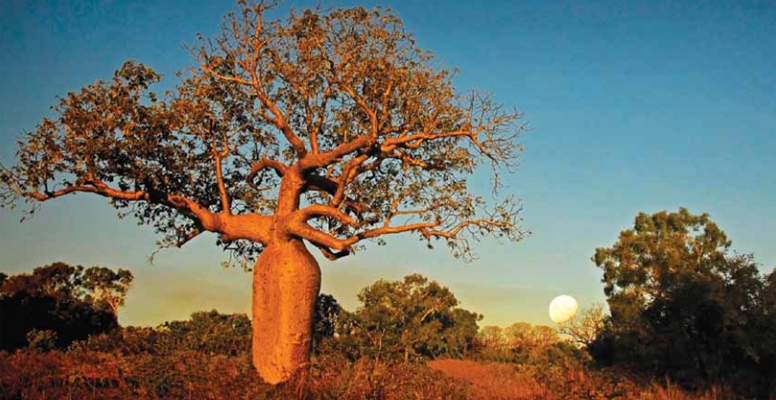

A wedge in the country's northwest corner, the Kimberley sprawls over about 115,000 square miles of stunning rainforest, sandstone gorges and stark ridges before smoothing out to where half a million cattle graze.

The marks of ancient indigenous cultures—whose heirs still reside there—are etched in rock walls. An estimated 22,000 humpback whales arrive yearly to breed just offshore, and the snub-nosed dolphin is the most recent new species found in an ongoing process of discovery.

The land and the waters off its coast make up one of the largest intact natural areas in the world, and they are the focus of a Pew-led protection campaign.

Mining projects alter the landscape and put sacred Aboriginal lands at risk. The expansion of mining has touched virtually everywhere in some fashion in the Northern Territory and Western Australia, and now the push is on in the Kimberley.

Protecting the Kimberley, and working with indigenous people to achieve that, is the goal of a campaign supported by Pew that includes backing an ambitious protection-area agenda by the state government.

“It's not that there can't be any mining,” Grady said, “but we certainly think that there's a much better approach that can be taken which will allow for economic development but which allows the people and the ecology of the Kimberley to have a long term future.”

The Great Western Woodlands

For a day and a half they drove into the wilderness, jolting down a two-track dirt road into a forest. The tree canopy and plant species changed from one mile to the next, the variety of birds and animals seemed to evolve at the same pace, and the overwhelming sense was that while man may have passed through before, there was no evidence he lingered long.

For a day and a half they drove into the wilderness, jolting down a two-track dirt road into a forest. The tree canopy and plant species changed from one mile to the next, the variety of birds and animals seemed to evolve at the same pace, and the overwhelming sense was that while man may have passed through before, there was no evidence he lingered long.

“It was like going back 30 million years,” said Pew's Kallick, recalling the expedition he and Traill took into the Great Western Woodlands, located amid the 62,000-square-mile wilderness in South West Australia known as Gondwana Link. “I can actually imagine that if you'd been alive at that time, it wouldn't have been very different.”

Traill agreed: “The Great Western Woodlands is by far the most intact Mediterranean woodlands ecosystem left on the planet.”

It is a place that was named, quite literally, by Pew and the others who seek to save it as a protected and well-managed preserve. Until fairly recently, it simply was known as “the bush around Kalgoorlie,” a town of about 30,000 people that sits beside an open-pit gold mine carved into the landscape.

“Conservationists gave it a name,” Traill said. “We gave it a status.”

In the woodlands, Pew works with Gondwana Link, a regional conservation organization. They support the Western Australian state government's efforts to provide long-term protection for the region.

On another day, Traill was driving through the Great Western Woodlands with a botanist, Wayne O'Sullivan.

“He said, ‘See that hill over there? There's a species of eucalypt that's only found on that hill.' ”

And that tree was not an exception, not in the Great Western Woodlands, not in all of Australia. Scores of unique species—trees, herbs and shrubs—that separated from their sister species 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, as Traill tells it, have “just been sitting there quietly on a hill and evolved into a new species.”