Why Are Millions of Citizens Not Registered to Vote?

A survey of the civically unengaged finds they lack interest, but outreach opportunities exist

Overview

In every state and the District of Columbia—except North Dakota—individuals who plan to vote in a federal election must first register to vote. However, a sizable share of eligible citizens do not register. Official statistics vary, but a conservative estimate, calculated using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent Voting and Registration Supplement, indicates that 21.4 percent were not registered to vote in 2014.1

Registration’s importance to the voting process and the large number of individuals who remain unregistered have spurred several major reforms intended to increase voter registration. Most notably, the federal government’s National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) requires that states allow eligible citizens to register to vote when completing other transactions at state motor vehicle and social services agencies, a provision commonly known as Motor Voter.2 Since enactment of the law, some states have expanded on this requirement by automating the Motor Voter process. Colorado upgraded its Motor Voter process in 2017, and Oregon became the first state to implement automatic voter registration in 2016, with at least six more planning to implement similar policies in the future.3 Other states offer Same Day Registration, which allows individuals to register and vote on Election Day, often right at their polling places.4

Despite these efforts, little is known about eligible but unregistered U.S. citizens’ exposure to opportunities to register, reasons for choosing not to, or attitudes toward the electoral system and civic engagement, or how many of them are interested in registering in the future. To begin to fill this gap, The Pew Charitable Trusts commissioned a nationally representative survey conducted in March and April 2016 that included a large population of unregistered individuals. This chartbook presents findings from the survey about the attitudes and experiences of those who said they were not registered to vote in the months preceding the 2016 presidential election, including:

- Less than 20 percent of eligible citizens have been offered the chance to register at a motor vehicle or other government agency.

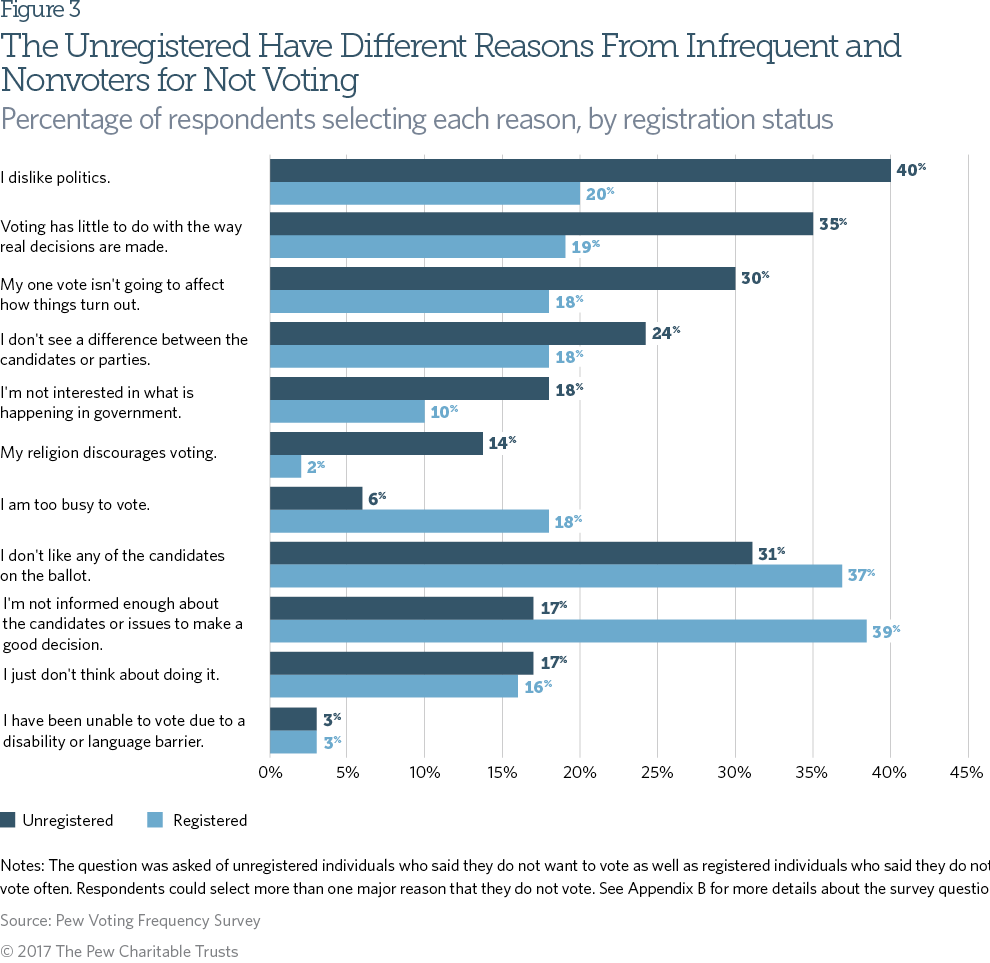

- The unregistered were more likely to say they do not vote because they dislike politics or believe voting will not make a difference, while people who are registered but vote infrequently say they do not vote more often because they are not informed enough about the candidates or issues.

- At least 13 percent of the unregistered, generally those who are younger and more civically engaged, say they could be motivated to register in the future.

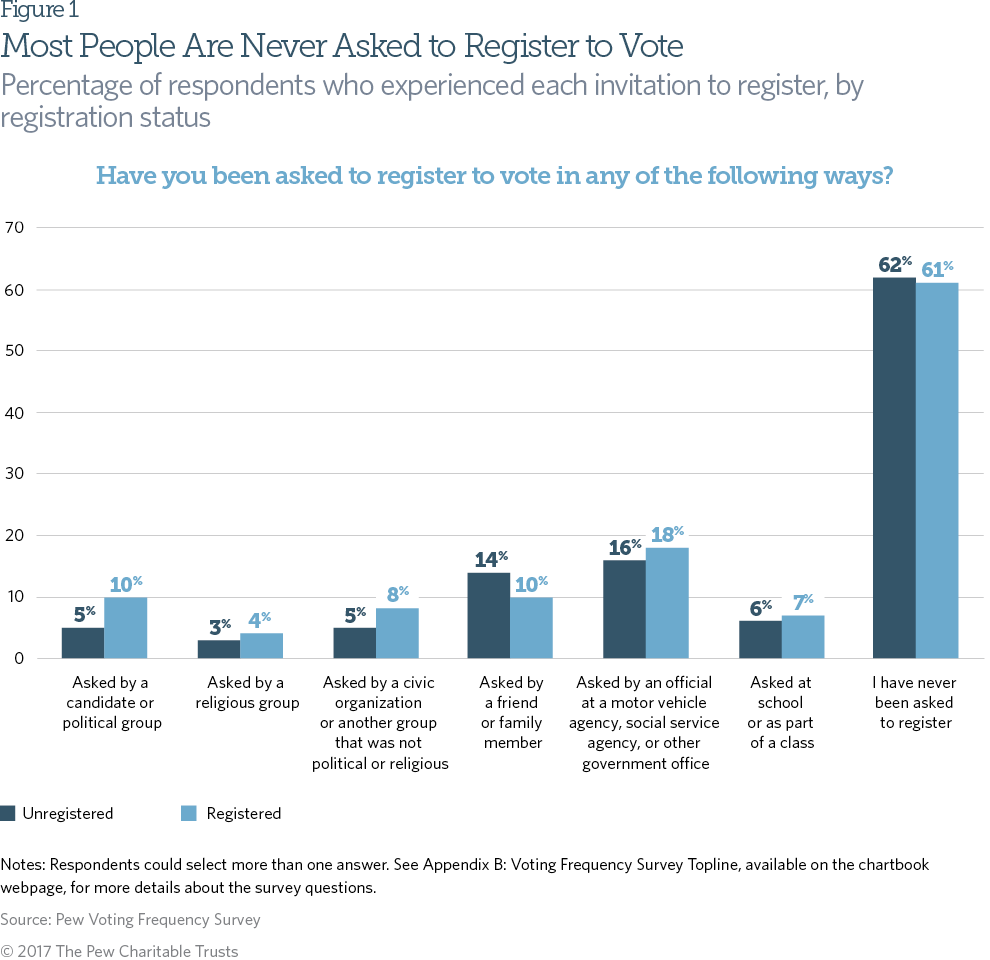

Because the American voting system requires individuals to register before they can vote, many political campaigns, nonprofits, religious organizations, and other groups hold voter registration drives. Despite these well-publicized efforts, more than 60 percent of adult citizens have never been asked to register to vote, and the rate was nearly identical among individuals who are and are not registered.5 Among respondents who had been invited to register, the most likely context was by an official at a motor vehicle agency, social service agency, or other government office. However, less than 20 percent of all those surveyed reported such an occurrence, which indicates that the NVRA has not been successful at reaching a large percentage of the population.

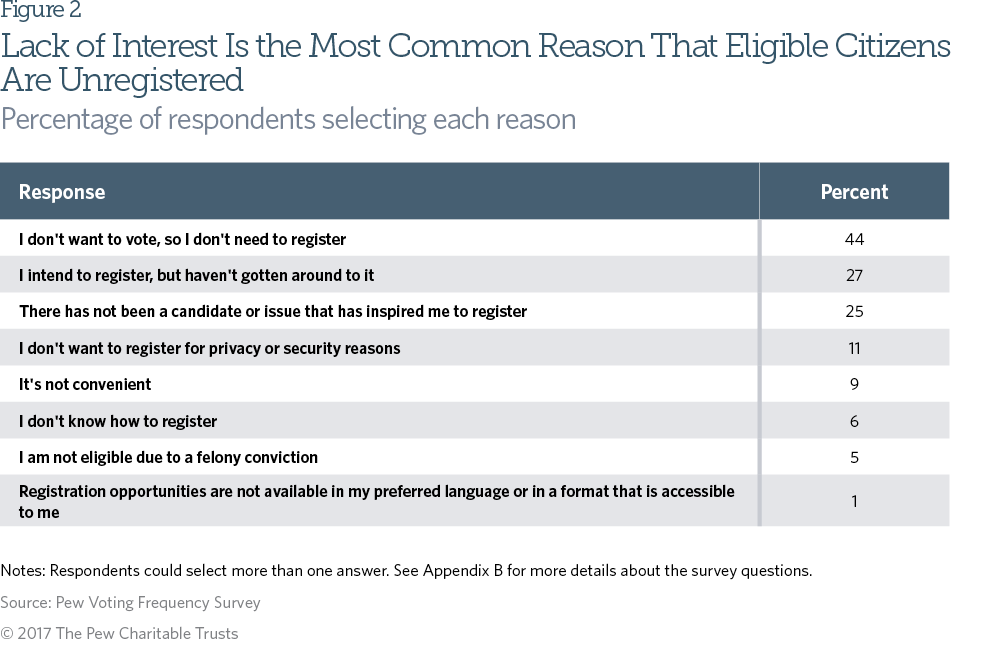

Forty-four percent of eligible unregistered individuals say they do not want to vote. Another 27 percent say they intend to register but haven’t done so yet, and 25 percent say they are unregistered because they have not been inspired by a candidate or issue. Eleven percent do not want to register due to privacy or security reasons. The survey was conducted before revelations in fall 2016 that hackers had targeted data from state voter registration systems, so the results do not reflect the public concern about the security of voter data that developed late in the campaign.6

The unregistered are more likely to indicate a broad distaste for the electoral system than registered individuals, who tend to give election-specific motives for nonvoting, such as disliking the candidates or not knowing enough about the issues. Forty percent of the unregistered say their aversion to politics is a major reason they don’t want to vote, and 35 percent say voting has little to do with the way real decisions are made, compared with 20 and 19 percent of registered but infrequent voters, respectively.

Previous research has found that many unregistered students feel they should not vote because they are insecure about their political knowledge.7 However, this survey found that only 17 percent of the unregistered population chose not to vote because they are too uninformed about the candidates or issues to make good decisions, compared with more than twice that amount—39 percent—of registered infrequent voters.

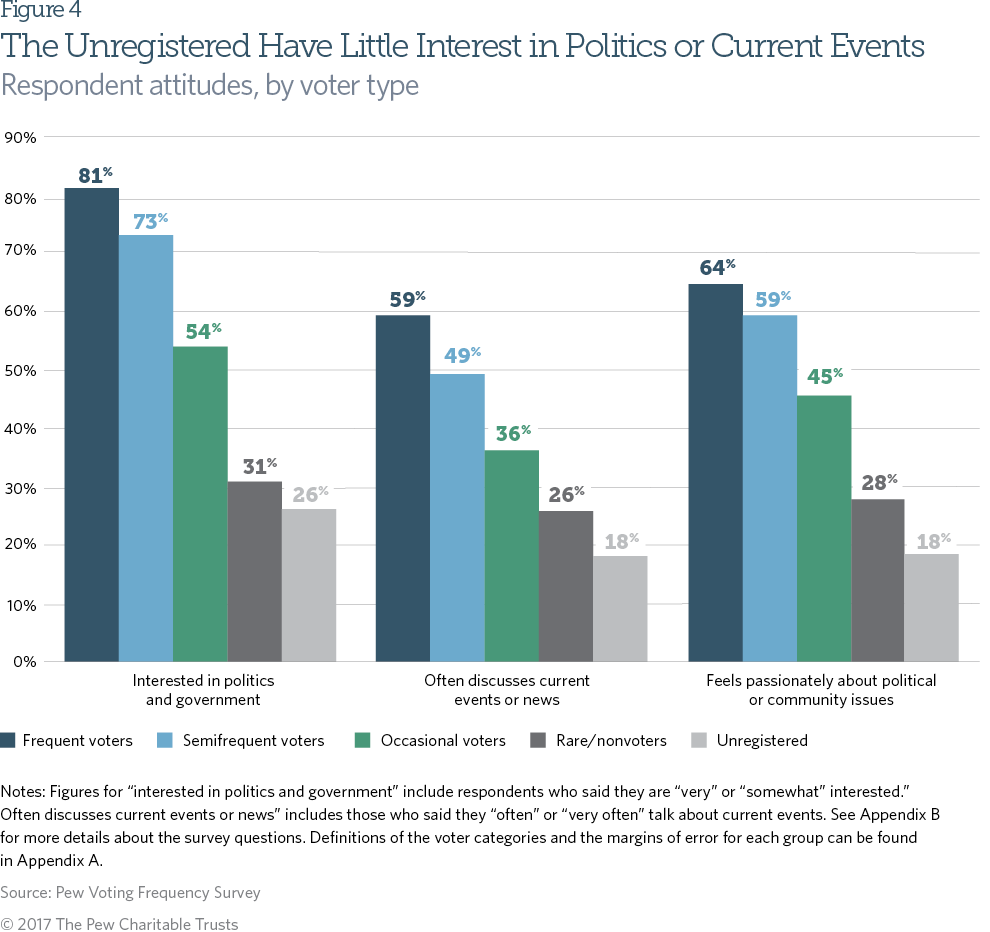

Some people vote in many types of races, while others turn out only for certain elections or are registered but never vote. For example, in 2016, approximately 60 percent of eligible citizens voted in the presidential election, but in the 2014 congressional races, turnout was less than 40 percent.8 To better understand how the unregistered population compares with these different groups of voters, the survey asked respondents to think about the various types of elections and evaluate how frequently they have voted since they were first eligible.9 Based on measures of people’s interest in government, current events, and political issues, unregistered individuals differ very little from those who are registered but rarely or never cast a ballot, while frequent voters are more than three times as likely as the unregistered to express interest in government.

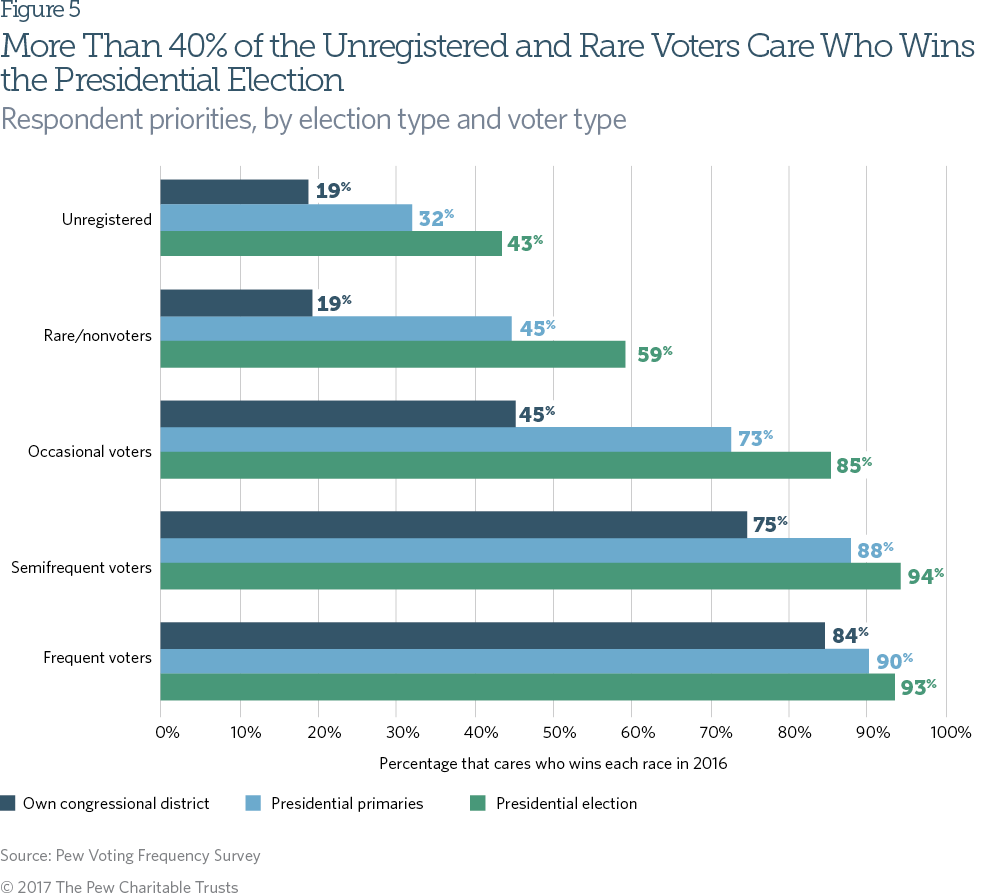

Despite not participating in elections, 43 percent of the unregistered and 59 percent of rare or nonvoters say they care a good deal who wins the presidential election. These groups expressed far less interest in the outcome of congressional races and presidential primaries, while frequent voters care about the winner of all three types of elections at very high rates. Although some of the unregistered may care who governs, many of these respondents still were not interested in participating in choosing the president: Just 38 percent said they intended to register but had not done so at the time of the survey, and 32 percent said they did not want to vote, probably because of their general belief that voting is disconnected from the way real decisions are made and their feeling that one vote would not affect the outcome of the election. (See Figure 3.)

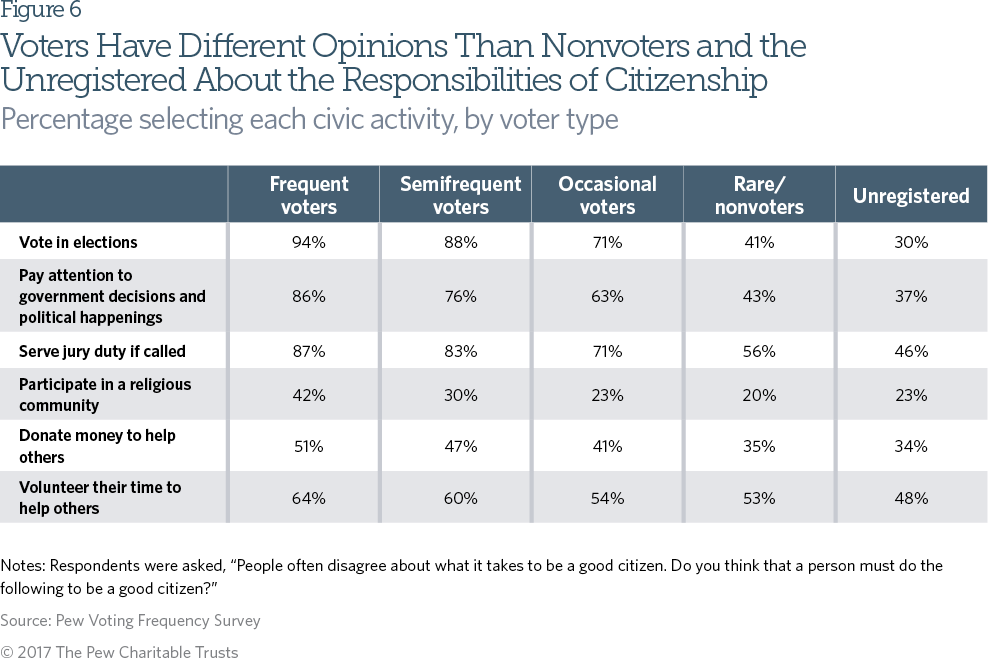

Voters diverge significantly from the unregistered in terms of their views about the behaviors that are necessary for a person to be considered a good citizen. Jury service was the most commonly selected behavior for good citizens across groups at 69 percent of all respondents. However, across groups, the priority on jury duty differed widely: Only 46 percent of the unregistered identified this as an essential responsibility of good citizenship, compared with 87 percent of frequent voters. Voters and the unregistered tended to be more like-minded about behaviors such as volunteering time to help others. Sixty-four percent of frequent voters and 48 percent of the unregistered said volunteering is something that a person should do to be a good citizen. Voting in elections and paying attention to politics were the two behaviors about which voters and the unregistered population differed most. Frequent voters were more than three times as likely as the unregistered to say voting is something that good citizens should do.

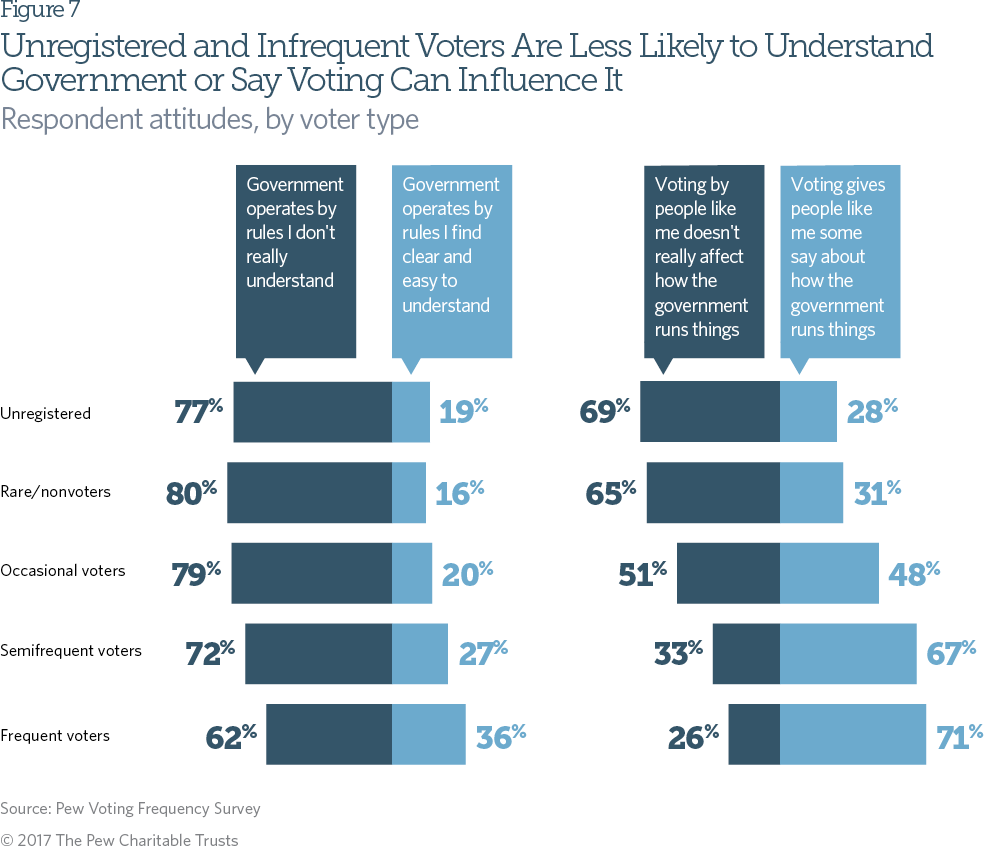

An individual’s belief that he or she is qualified to understand and participate in politics is considered a key metric for inferring engagement in the political system.10 All groups, except the most frequent voters, reported that the rules of government are difficult to understand at roughly similar— and high—rates. But when asked if voting could influence the way the government is run, the unregistered and rare or nonvoters both tended to say it does not, which very clearly diverged from more frequent voters, who largely said voting does affect governance.

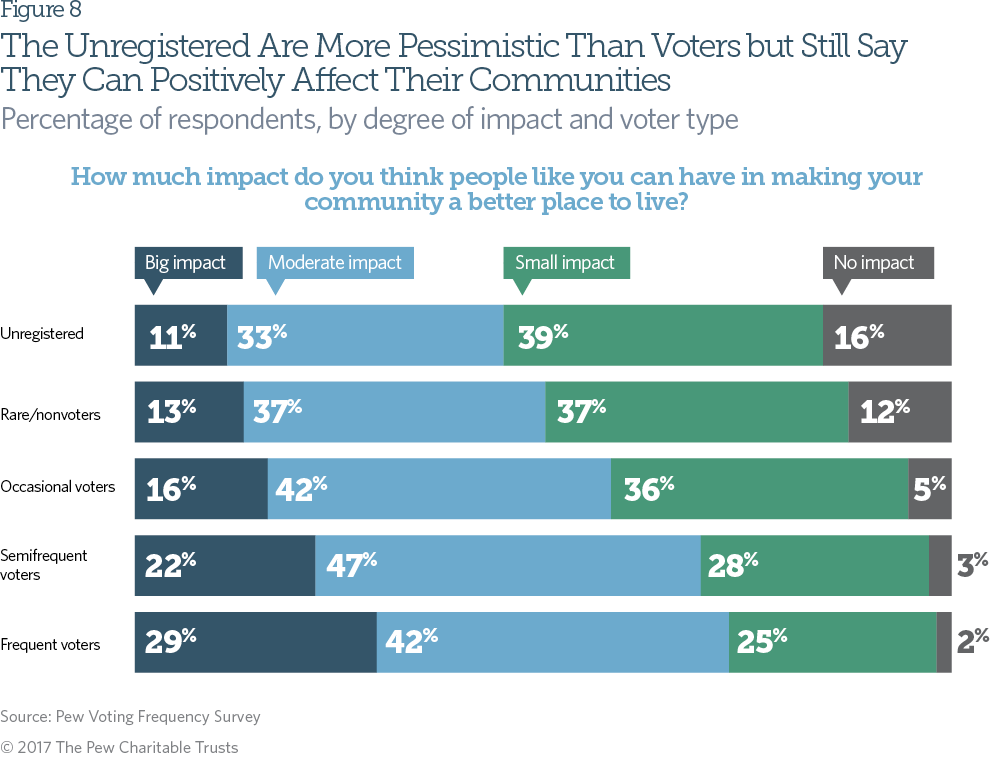

Most people, including more than 80 percent of the unregistered population, said they could have at least a small positive impact on their communities. Occasional, semifrequent, and frequent voters were all most likely to say they could have a moderate effect, while rare and nonvoters were equally likely to choose moderate or small. The largest share of unregistered respondents said they could have only a small impact.

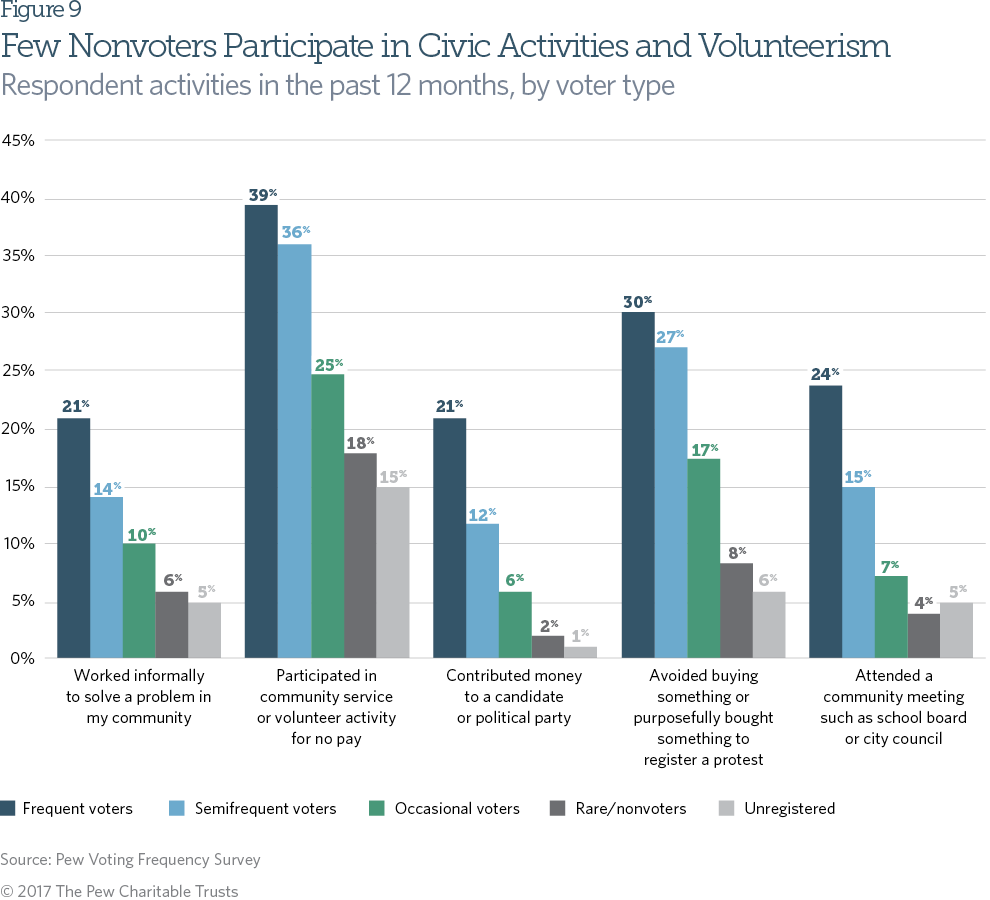

Given that nonvoters and the unregistered have limited confidence in their ability to affect their communities, the fact that they are less likely to engage in civic and volunteer activities than groups who vote more frequently is not surprising. Across different types of activities, the unregistered and nonvoters participate more often in those that are not political in nature. Only 1 percent of the unregistered have donated money to a political candidate or organization, and just 5 percent have attended a community meeting. However, 15 percent have done unpaid volunteer work. The civic behaviors of the unregistered population did not differ significantly from those of respondents who rarely or never vote and, in some cases, occasional voters were nearly as disengaged.

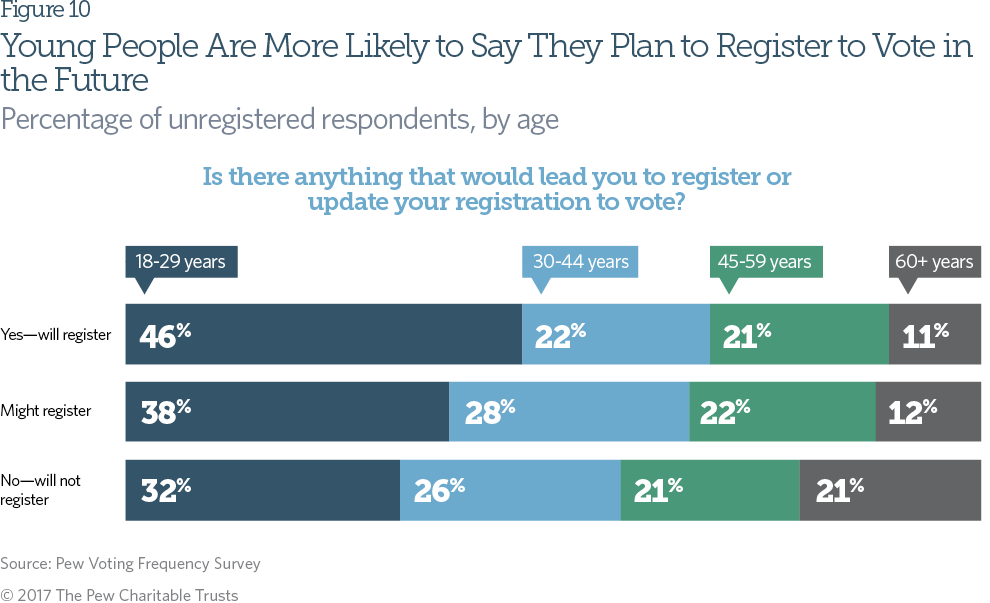

Among the unregistered population, responses differed about possibly registering to vote in the future. Overall, 43 percent of the unregistered said nothing would motivate them to register, 13 percent said something might, and 44 percent were undecided. Those who were open to registration tended to be younger: Forty-six percent of those who said they would register were between 18 and 29 years old, compared with 21 percent ages 45 to 59 and just 11 percent 60 or older.

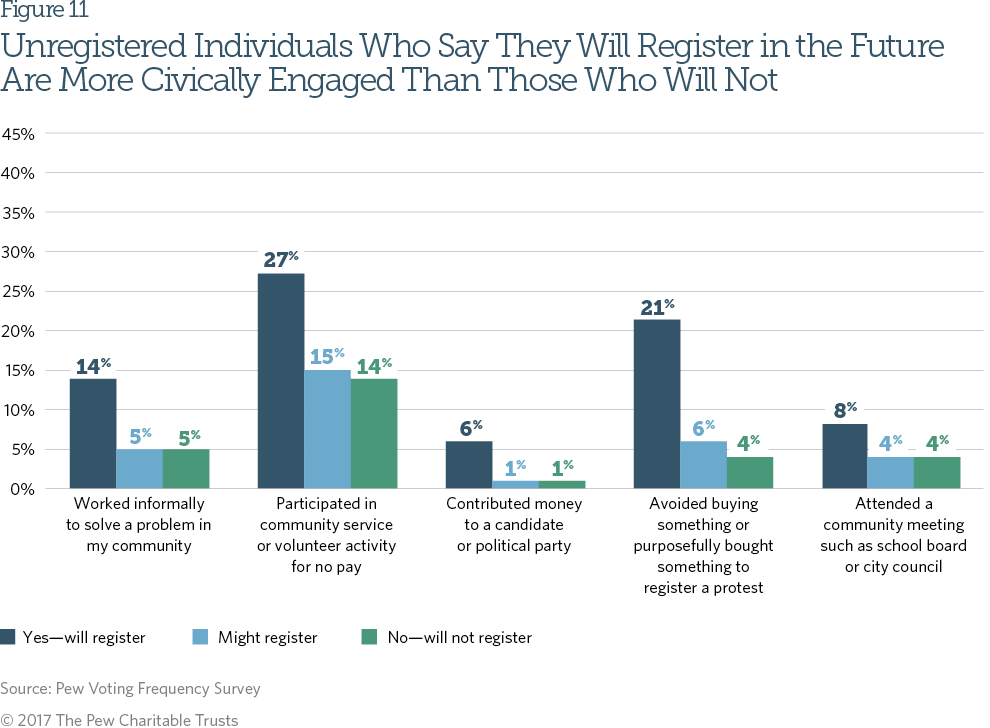

Among the unregistered, those who said they would register reported patterns of civic engagement that closely resembled those observed for occasional or semifrequent voters. Fourteen percent of unregistered individuals who said they would register and semifrequent voters had worked informally to solve a problem in their community, and 21 and 27 percent of those groups, respectively, had engaged in economic protest. Similarly, 27 percent of those who would register had done unpaid volunteer work, 6 percent had contributed money to a candidate, and 8 percent had attended a community meeting, all which closely track the rates among occasional voters (25 percent, 6 percent, and 7 percent, respectively. See Figure 9.)

Conclusion

The unregistered differ in many ways from those who vote frequently: They are less interested in politics, less engaged in civic activities, and more cynical about their ability to understand and influence government, but they are not appreciably different on these measures from individuals who are registered but rarely vote. However, the unregistered population is not entirely unengaged from civic life; some indicated that they would register, and that group also reported participating in community or political activities at rates similar to occasional and semifrequent voters. Further, more than 40 percent of the unregistered cared who would win the presidency in 2016, and some indicated that they could be motivated to register in the future, though many also feel that the voting process does not affect the way governing decisions are made. These findings suggest that opportunities exist to engage segments of the unregistered population, including through consistent outreach at motor vehicle agencies as required under the NVRA and public education campaigns designed to highlight the significance of individual voter participation to election outcomes and the connection between local policies and issues these citizens care about, such as those for which they volunteer in their communities. Less than 20 percent of this group has been asked to register by a state agency, and a substantial increase in that figure could help to improve registration rates and electoral participation among these disconnected citizens.

Methodology

The Voting Frequency Survey was conducted online in English and Spanish from March 25 to April 19, 2016, by the GfK Group on behalf of The Pew Charitable Trusts. The total sample size was 3,763 U.S. citizens 18 years or older. GfK sampled households from its KnowledgePanel, a probability-based, nationally representative web panel. The margin of error, calculated with the design effect, at the 95 percent level of confidence for the total sample is plus or minus 1.9 percentage points. A full methodology, including margins of error for key subgroups, is given in Appendix A: Voting Frequency Survey Methodology, available on the chartbook webpage. The survey questions and frequencies are available in Appendix B: Voting Frequency Survey Topline.

Endnotes

- The Census Bureau calculated that 35.4 percent of eligible citizens were not registered to vote in 2014, as reported in “Who Votes? Congressional Elections and the American Electorate: 1978-2014,” July 16, 2015, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p20-577.html. However, researchers agree that this calculation artificially inflates the percent of the population that is unregistered because it includes those who were not asked or did not answer the registration question in the Voting and Registration Supplement as being unregistered. More information on the method for adjusting the registration rate can be found in The Pew Charitable Trusts, Elections Performance Index: Methodology (August 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2016/08/epi_methodology.pdf.

- The National Voter Registration Act applies to 44 states and the District of Columbia. Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming are exempt because at the time the law was implemented, they offered Election Day registration or had no registration requirements.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Automatic Voter Registration,” March 8, 2017, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/automatic-voter-registration.aspx.

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Same Day Voter Registration,” Jan. 11, 2017, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/same-day-registration.aspx.

- Differences are within the margins of error, which are 3.62 percentage points for the subgroup of unregistered respondents and 2.21 percentage points for registered voters.

- Eric Geller and Darren Samuelsohn, “More Than 20 States Have Faced Major Election Hacking Attempts, DHS Says,” Politico, Oct. 3, 2016, http://www.politico.com/story/2016/09/states-major-election-hacking-228978.

- D.J. Neri, Jess Leifer, and Anthony Barrows, “Graduating Students into Voters” (April 2016), http://www.aascu.org/programs/ADP/StudentsintoVoters.pdf.

- Michael P. McDonald, United States Elections Project,“Voter Turnout,” accessed Feb. 6, 2017, http://www.electproject.org/home/voter-turnout/voter-turnout-data.

- The question asked: “There are many types of elections such as federal elections for president and members of Congress, primary elections where voters choose party nominees, local elections for city council and school board, and special elections when vacancies arise in between scheduled elections. Which best describes how often you vote, since you became eligible? Every election without exception, Almost every election – may have missed one or two, Some elections, Rarely, Don’t vote in elections.” The four frequencies of voting reflect respondents’ answers to the question of how often they vote. Individuals who answered “Every election without exception” are defined as frequent voters, “Almost every election – may have missed one or two” are semifrequent voters, “Some elections” are categorized as occasional voters, and the answers “Rarely” and “Don’t vote in elections” were combined into a group called rare or nonvoters, both due to sample size and because these two groups were nearly identical on key measures.

- Richard G. Niemi, Stephen C. Craig, and Franco Mattei, “Measuring Internal Political Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study,” The American Political Science Review 85, no. 4 (1991): 1407–13, doi:10.2307/1963953.