Employer Barriers to and Motivations for Offering Retirement Benefits

Insights from Pew’s national survey of small businesses

This brief was updated on September 5, 2017, to accurately reflect two survey questions that looked at how business conditions affect whether employers offer retirement plans. The questions asked whether earnings had increased or employees had been added in the past year, not the past two years.

Overview

One-quarter of private sector workers in the United States lack access to a workplace retirement savings plan, making it difficult for them to build the resources needed to support themselves after their working years.

Although Social Security and personal earnings or savings contribute to retirement security, most Americans save through employer-provided plans, but even those with such plans face challenges accumulating enough money for their retirements.

Research shows that workers at small- to medium-sized businesses—those with five to 250 employees—are least likely to have access to retirement savings options. To improve retirement security and to reduce future government spending on social services for the elderly, many states are looking at ways to increase access to private sector employer-sponsored retirement plans. Policymakers are considering legislation to help employers start their own plans—for example, through online marketplaces or multiple employer plans—or looking to set up state-or city-sponsored individual retirement account (IRA) plans that automatically enroll private sector workers who do not have access to workplace plans.1

When crafting their approaches, it is useful for states to understand why some employers offer plans and others do not. In 2016, The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted a survey of owners, top executives, and human resource managers at more than 1,600 private sector, small and midsize businesses nationwide. One focus of the survey was to identify the obstacles to, and motivations for, offering plans and to gather data on what plans are currently offered and plan characteristics. For example, do they include matching contributions, automatic enrollment, or automatic escalation of contributions? The survey, one of the few focused on retirement plans since the Great Recession, includes employers that do and do not offer retirement benefits to their workers.

In conjunction with Pew focus group research, the findings show that employers care about their employees’ financial well-being but are concerned about potential costs, administrative capacity, and familiarity with the options when considering whether to offer a plan.2 In addition, 93 percent believe that their workers would prefer a higher salary over better retirement benefits.

Among the survey’s key findings:

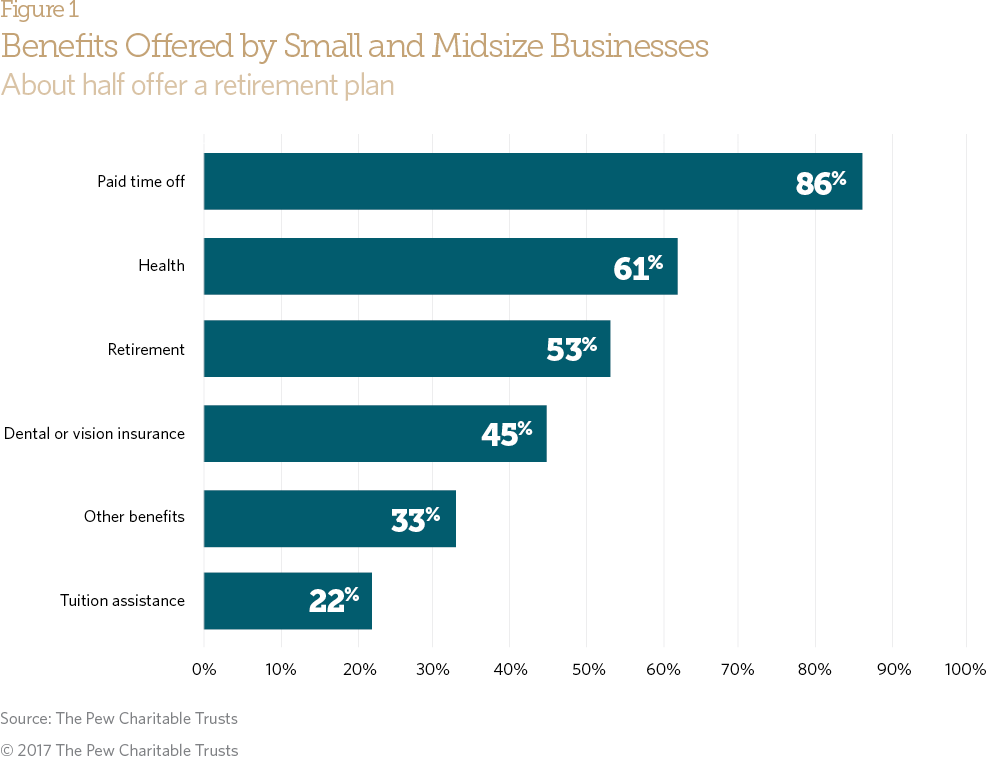

- Just over half of the small and midsize businesses surveyed offer a retirement plan; many are more likely to offer paid time off and health plans than retirement benefits.

- Firms that are more likely to offer retirement plans are often older and larger, have more full-time employees, outsource their payroll, or have had increasing earnings in recent years. The likelihood of adding a plan grows fastest in a firm’s first few years or as it approaches 75 employees. This suggests that businesses may need to reach a point of financial stability before taking on responsibility for a retirement benefits program.

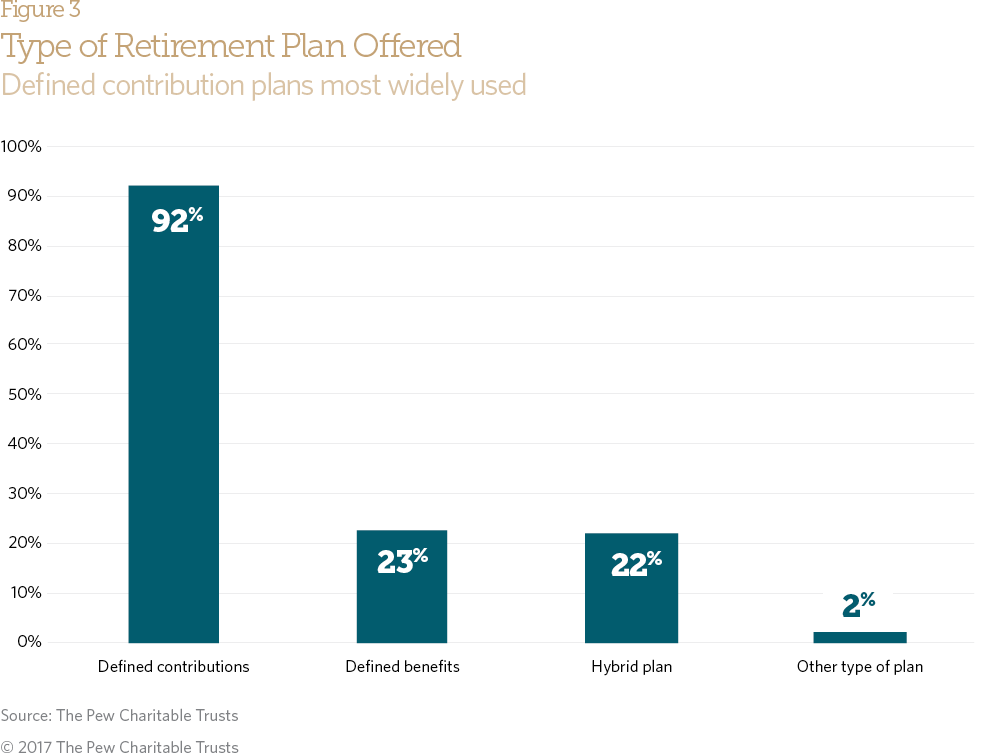

- More than a third of employers that sponsor a plan offer more than one type. Options include defined contribution plans, such as a 401(k)s; traditional pensions; or hybrid plans that combine elements of both. Defined contribution plans are most common.

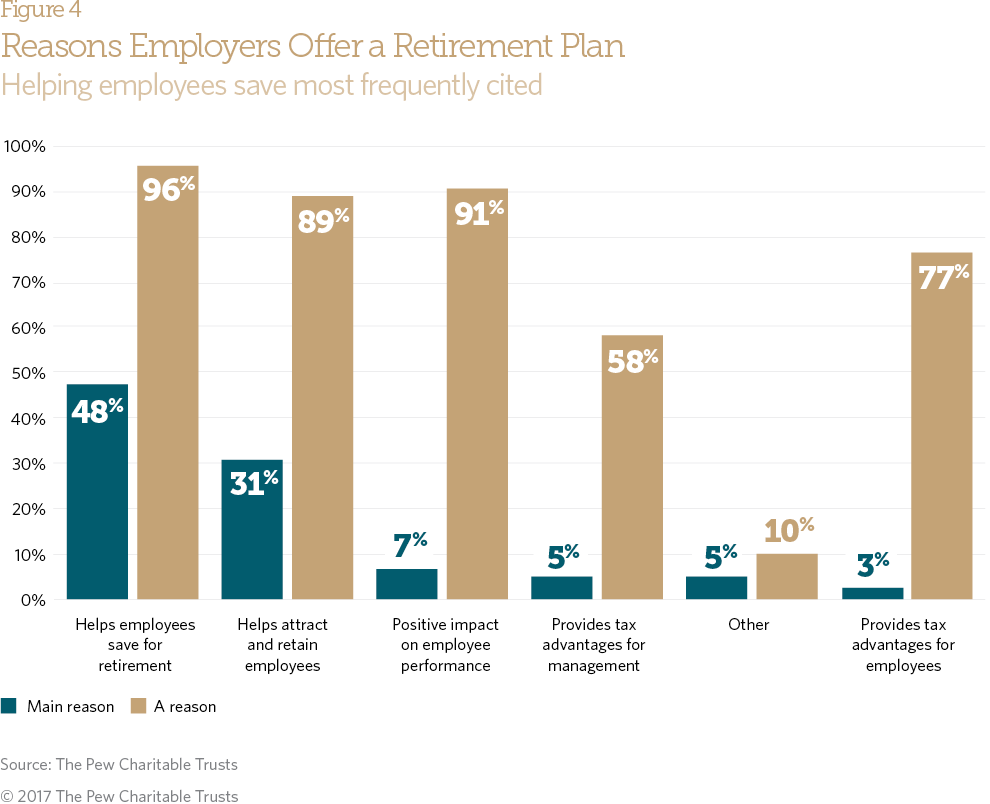

- Employers most often mention helping workers save for retirement and attracting and retaining employees as the main reasons they offer plans.

- Most employers that sponsor a plan make contributions, which boosts employee participation and helps build retirement savings more quickly.

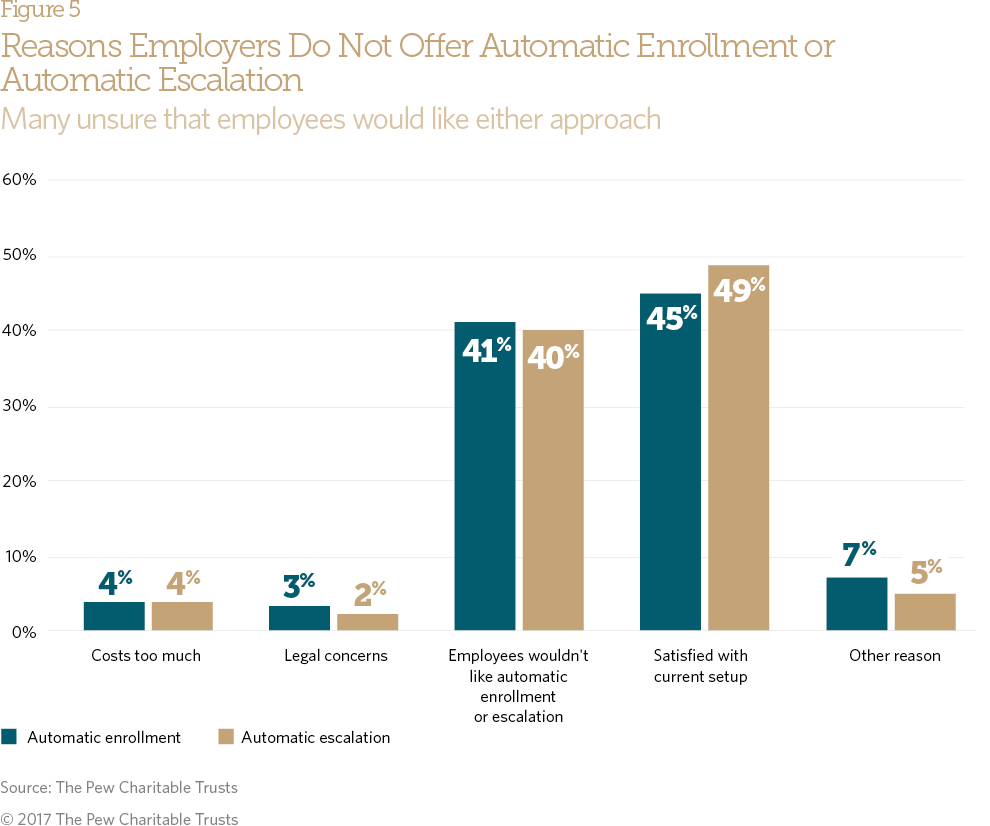

- Relatively few employers use features known to boost participation and savings in retirement plans; just 32 percent use automatic enrollment, while only 14 percent use automatic escalation of contributions.

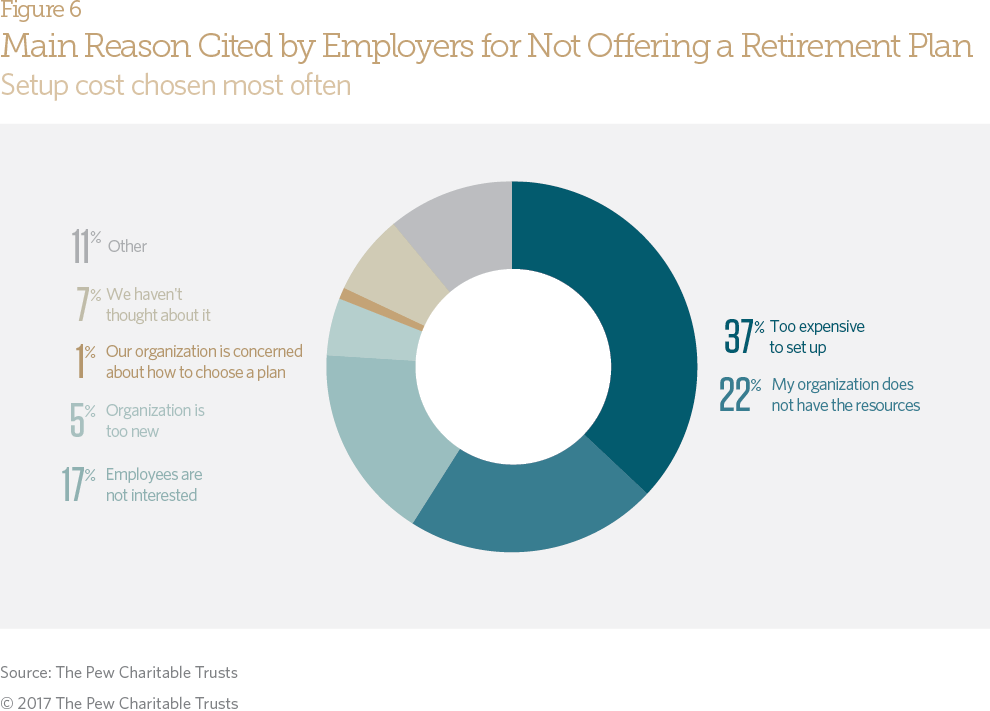

- Employers that do not offer plans pointed to the financial cost (37 percent) and organizational resources (22 percent) needed to start a plan as barriers. One-sixth said they do not offer a plan because their employees are uninterested.

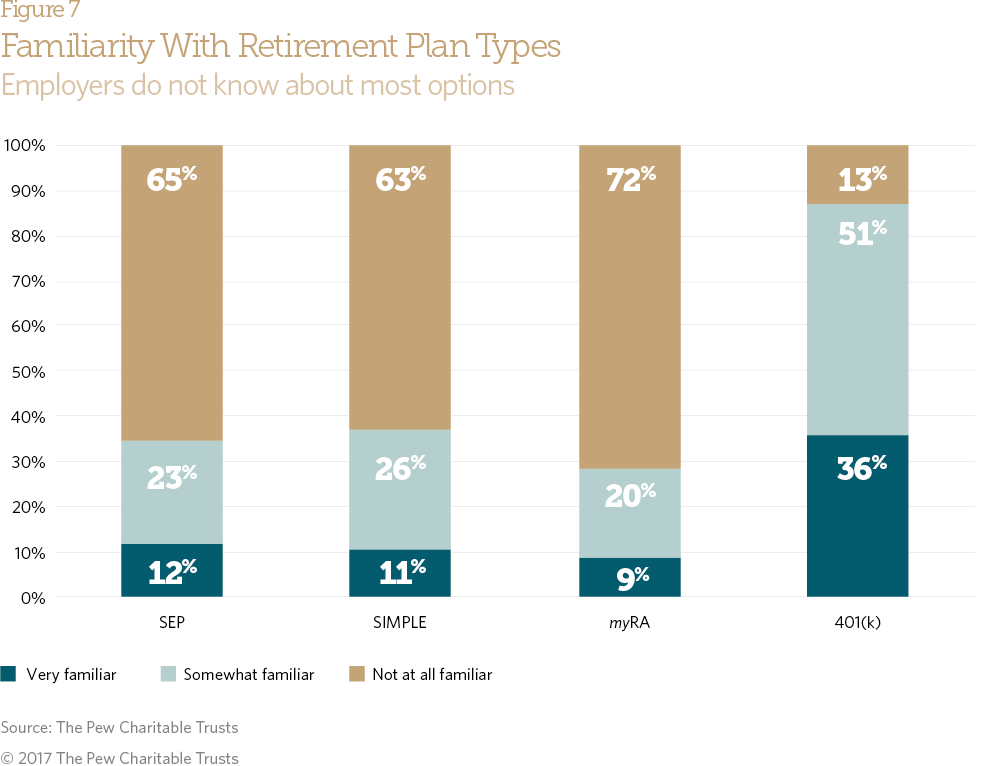

- A lack of employer familiarity with retirement plan options can be a barrier to sponsoring one. While most employers were at least somewhat familiar with 401(k) plans, far fewer knew about Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) plans, Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE) IRAs, or myRAs, all of which are designed for small firms or individuals.

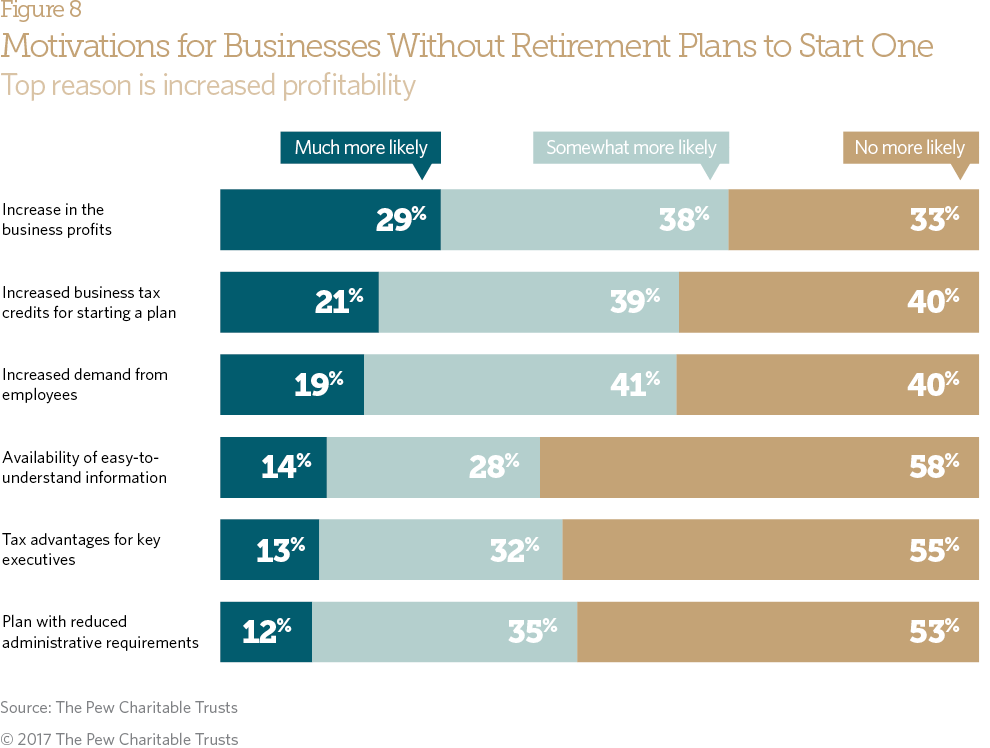

- Respondents without plans most frequently said that increased profits and tax credits to offset the expenses of starting a plan would make offering retirement benefits more likely. However, those who cited “cost” as a significant barrier were no more likely than others to believe that tax credits or increased profits would motivate them to start a plan. This contradiction suggests that employers face a number of obstacles when making these decisions.

Many factors influence whether employers provide retirement benefits

Just more than half—53 percent—of the small and midsize employers surveyed offer a retirement plan to their workers. Ninety-three percent said they believe that their employees would prefer higher salaries over better retirement benefits, which may be why many put a greater priority on pay and other benefits—such as paid time off and health plans—rather than retirement plans.

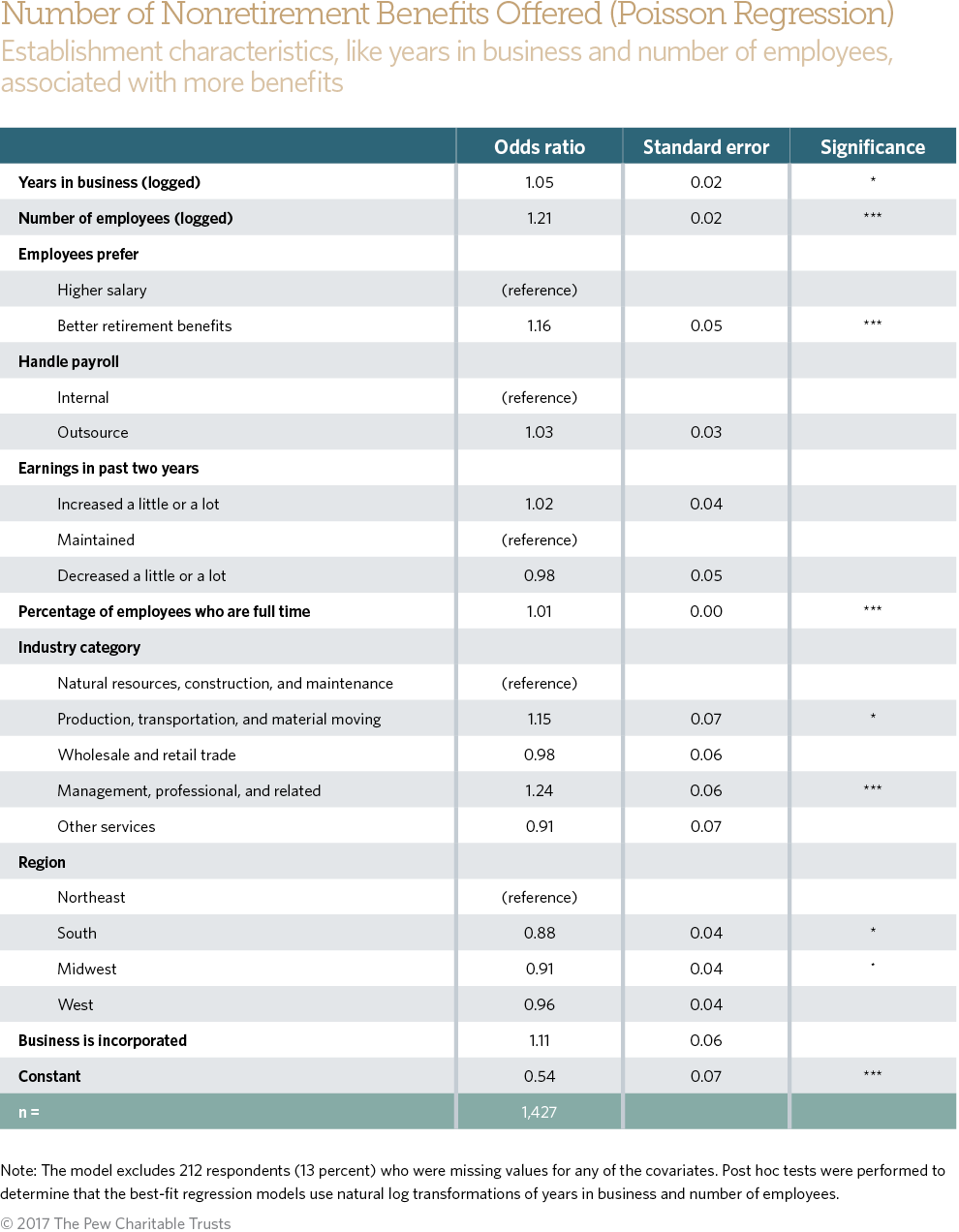

On average, employers offer three types of benefits. Figure 1 shows that businesses are more likely to offer paid time off (86 percent) and health care plans (61 percent) than to sponsor a retirement plan. Paid time off and health insurance serve workers’ immediate needs, while retirement savings represent a commitment to divert current financial resources for future needs.3

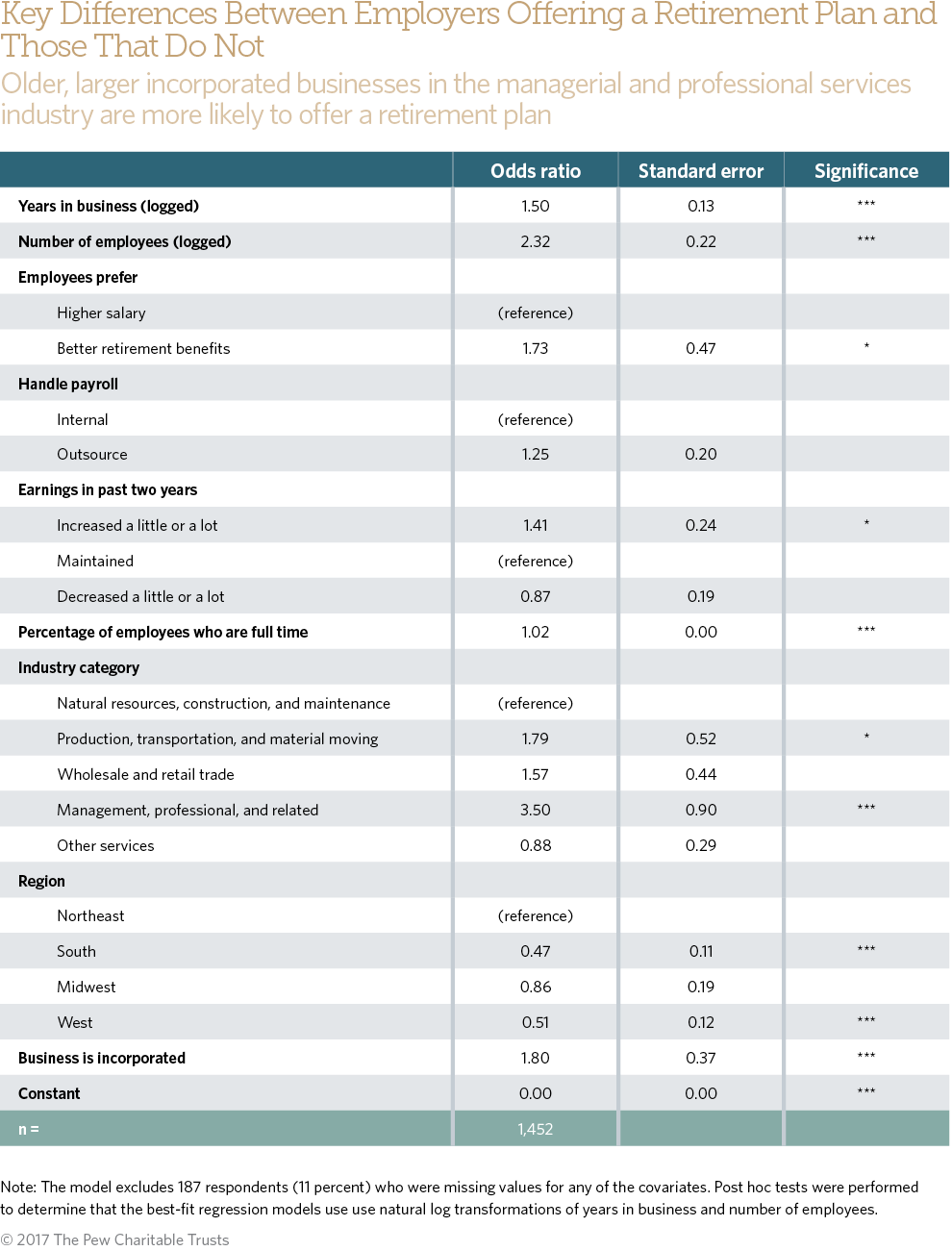

Business and labor force characteristics are key factors in whether employers offer a retirement plan. When earnings increased “a little” or “a lot” over the past two years, businesses were 41 percent more likely to offer a plan than if earnings had remained flat. Businesses with a higher percentage of full-time workers also are more likely to offer a plan that those with more part-time employees. On average, there is a 66 percent likelihood that a firm that employs all full-time workers will offer a plan compared with a 44 percent chance for a company with a workforce divided evenly between full- and part-time workers.4

The type of business matters, too. Incorporated businesses are 1.8 times more likely to offer a plan than nonincorporated businesses, even when controlling for the number of employees. Corporate status may signal that a firm is growing or stable enough to support offering more benefits.

In terms of industry, businesses classified as management and professional or as production, transportation, and material moving are more likely than those in natural resources, construction, and maintenance to offer retirement plans. The differences may reflect the fact that some industries typically have more full-time workers and are therefore more likely to provide benefits; employers within certain industries also use retirement benefits to compete for talent.5

In addition, employers in certain industries may be more financially stable than in others, creating an environment that supports retirement plan sponsorship or encourages employee demand for the plans because they have lower turnover and fewer seasonal workers.

When asked about what they believe their employees prefer—better retirement benefits or higher salaries— those who said their employees would prefer better retirement benefits are 73 percent more likely to offer a plan than those who said the reverse.

Region also plays a role. Businesses in the South and in the West are about half as likely to offer plans as those in the Northeast. This mirrors Pew’s analyses of state-by-state access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, which showed that full-time, full-year employees in Florida, New Mexico, and Texas reported the lowest rates of access to plans.6 Geographic differences can be attributed in part to regional concentrations of certain industries, such as leisure and hospitality. Employer size and employee demographics also vary by state and region.7 (See Appendix Table 1 for full regression results.)

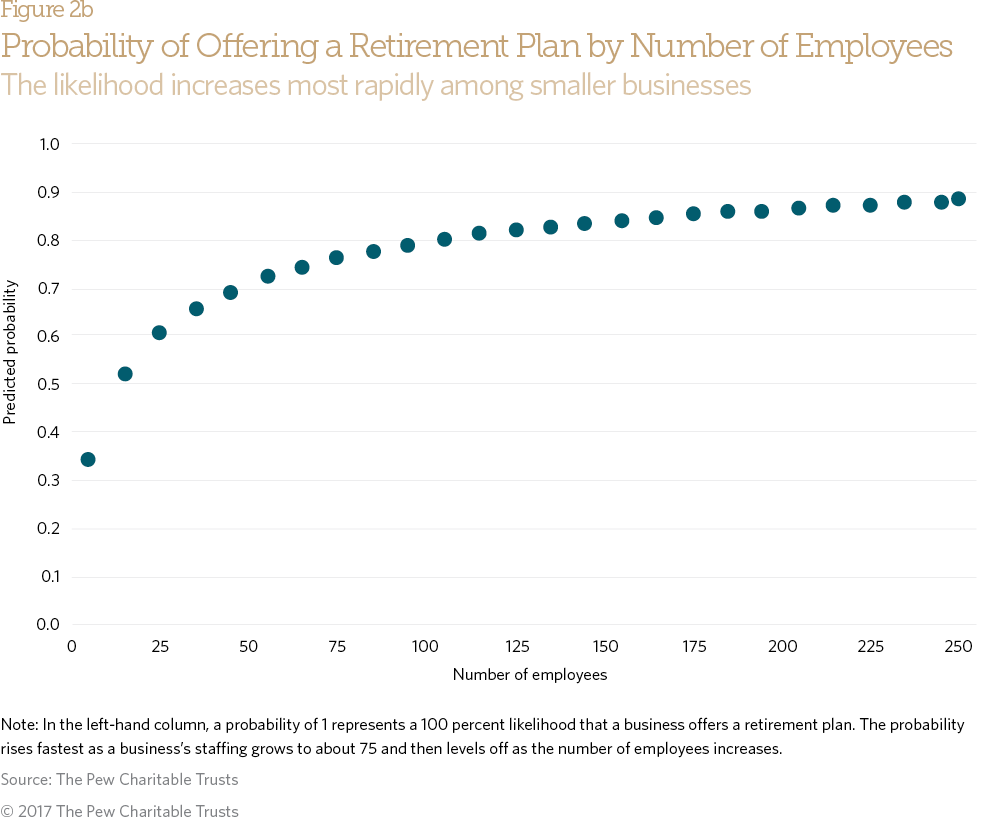

Not surprisingly, larger, older businesses are more likely to offer plans, but the relationship is not linear. Businesses are more likely to adopt plans in the early stages of growth, but that likelihood tapers off after a certain point. For example, the probability that the average business with five employees offers a retirement plan is just 34 percent, while the probability for the average business with 55 employees to do so is a little more than twice that—72 percent. The probability continues to grow as staffing increases, but at a much lower rate.

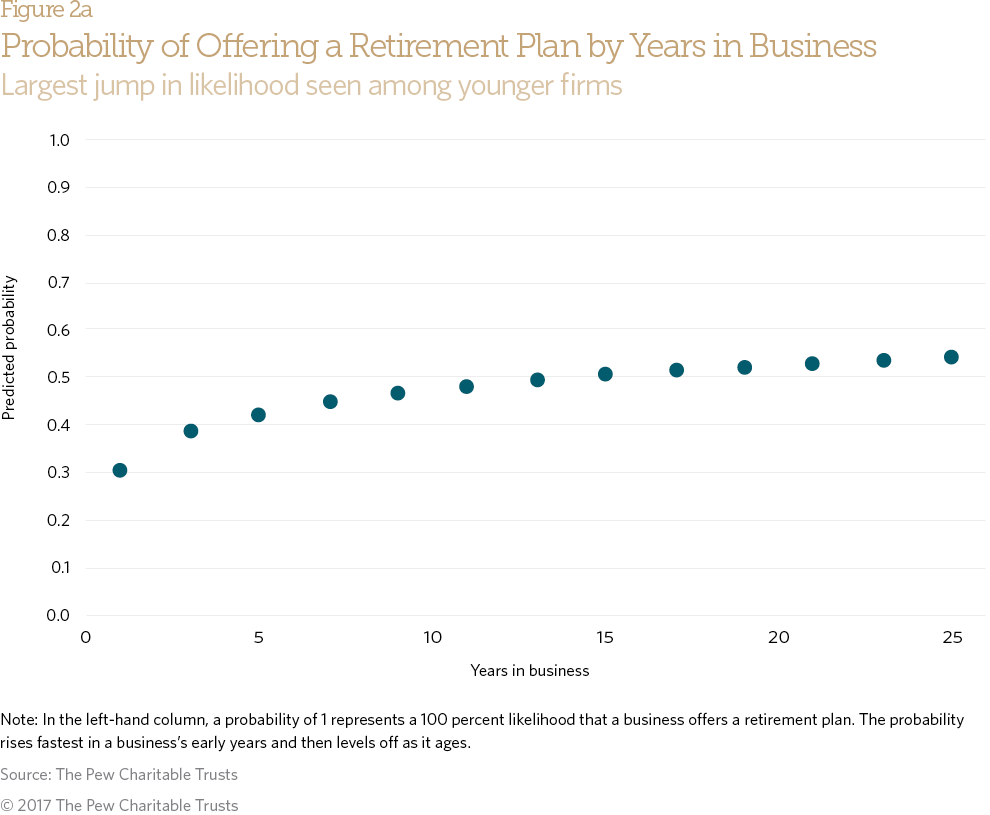

Meanwhile, a 3-year-old firm is 25 percent more likely to offer a retirement plan than a 1-year-old firm. That increase in probability diminishes as companies age. For example, one in business for 13 years is only 3 percent more likely than one in business for 11 years to offer one.

These results suggest that businesses tend to adopt plans during a “middle” phase in their development, after startup and during a period of expansion and growth. At such a time, retirement benefits may be an attractive tool for hiring and retaining talented employees when an employer already has provided other benefits to workers, such as health insurance. When addressing barriers, such as limited knowledge and startup costs, state policies could specifically target younger, less established businesses.

Employers’ motivations for offering a retirement plan

Employers have several retirement plan options that offer tax advantages for their workers.8 Survey findings support earlier research indicating that employers typically provide retirement benefits to attract and retain talent, as well as to help their workers save.9 Still, the survey data show that few employers use pro-savings tools, such as automatic enrollment and automatic escalation, to encourage putting away more money for retirement.

Some 92 percent of employers that provide retirement benefits said they offer a defined contribution plan, such as a 401(k), a SIMPLE plan, or a profit-sharing plan. Twenty-three percent said their business offers a defined benefit plan, such as a traditional pension, while 22 percent said they offer a hybrid plan that includes both a defined contribution and a defined benefit plan. Another 35 percent reported that their business offers more than one retirement plan type.

Employers offered various reasons for providing retirement plans. (See Figure 4.) Almost all—96 percent—cited a desire to help employees save for retirement, and 48 percent identified it as the main reason. In Pew focus groups, small to midsize employers repeatedly said that offering a retirement plan helped them to attract quality employees.10 In the survey, 91 percent said they felt that offering a retirement plan had a positive impact on employee performance, while 89 percent said doing so helped attract and retain employees. Nearly a third—31 percent—said attracting and retaining workers was the main reason they offered a plan. Tax advantages for management and employees were cited much less often as main reasons (5 percent and 3 percent, respectively).

Employers in the survey were also likely to contribute to workers’ plans. Among those with defined contribution plans, 89 percent contribute and 82 percent of those that contribute said they match worker contributions.

Relatively small percentages of plan providers use plan options that policy researchers say are effective in encouraging workers to save.11 About a third automatically enroll their workers (with employees retaining the option to opt out), while about a sixth use automatic escalation, which increases employee contributions annually until a certain maximum percentage is met. About 48 percent of employers said they offered retirement benefits primarily to help their workers save. Still, those who said this was a reason were no more likely to use these pro-savings features than those who did not cite this as a reason they offer benefits.

When asked why they do not offer features that encourage participation and savings such as automatic enrollment or automatic escalation, executives and other leaders were most likely to say their businesses were satisfied with their current setup (45 percent in response to automatic enrollment and 49 percent in response to automatic escalation). In addition, about 4 in 10 said that employees would not like automatic enrollment (41 percent) or automatic escalation (40 percent). Few cited legal or cost concerns.

These pro-savings tools are fairly common among large employers, but smaller businesses and their workers may not be as familiar with the workings and benefits of auto-enrollment and auto-escalation. Even if familiar with them, however, small employers may have concerns about how their employees would react to these features. Unlike larger corporations, these employers have more direct involvement with employees and are more aware of their attitudes and specific preferences.

Top barriers to offering a retirement plan

Many employers said they would like to offer retirement savings options but feel they face numerous barriers to doing so. Some business representatives in focus groups cited limited demand for retirement benefits because their workers earned low wages or were working short term, in addition to the costs and resources required to start and maintain a plan.12 The survey data generally support all these focus group findings regarding barriers. Policies that take a multipronged approach can help to address the range of possible barriers.

Most commonly, employers without plans said that starting a retirement plan is too expensive to set up (37 percent). Another 22 percent cited a lack of administrative resources. In focus groups, some business representatives said their mix of workers—especially if they included low-wage or short-term employees— translated into limited employee interest in or demand for retirement benefits. But in the survey, only 17 percent cited lack of employee interest as the main reason they did not offer a plan.

Lack of familiarity with retirement plan options also can prove to be a barrier to providing one. In the survey, 11 percent of employers said they were not familiar with 401(k) plans, SEPs, SIMPLE plans, and myRAs.13 Just 13 percent said they were at least somewhat familiar with all four, while 34 percent said they were only familiar with the 401(k). Leaders of small and midsize businesses were much less familiar with the other three alternatives, even though SEPs and SIMPLE programs are specifically intended to appeal to smaller employers because they are cheaper to establish and administer.

Key Elements of Select Defined Contribution Plans

- 401(k): Can be established by employers. Employees younger than 50 can contribute up to $18,000 a year in pretax money; those 50 or older can contribute up to $24,000. Employers can contribute up to $54,000 annually. Employees may borrow from these accounts.

- Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE): Can be established by employers that do not offer a retirement plan and have up to 100 employees. Employees can contribute pretax money up to $12,500 a year; those 50 or older can contribute up to $15,500. Employers must make contributions—either matching what employees save up to 3 percent or a flat 2 percent of employee compensation—for those who made at least $5,000 in the previous calendar year. Employees may not borrow from these accounts but can make withdrawals subject to penalties in many cases.

- Simplified Employee Pension (SEP): Employees cannot contribute. Employers make annual contributions that cannot exceed the lesser of 25 percent of compensation or $54,000 for employees who have worked at the business for three of the past five years, are 21 or older, and received at least $600 in compensation. Employees may not borrow from these accounts but can make withdrawals subject to penalties in many cases.

- myRA: Can be established by employees. Employees can contribute after-tax money up to $5,500 a year, except those 50 or older, who can contribute up to $6,500, with a total lifetime limit of $15,000. Employers cannot contribute. Employees can make tax-free withdrawals from the account at any time. Sources: Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Treasury Department

Sources: Internal Revenue Service and U.S. Treasury Department

When businesses without a retirement plan were asked which circumstances were most likely to motivate them to begin one, the most common responses were a change in their financial situation or government incentives. Some 67 percent said increased business profits would make them somewhat or much more likely to start a retirement plan. Similarly, 60 percent said they would be somewhat or much more likely to start a plan if there were increased business tax credits for doing so. On the other hand, majorities said that availability of easy-to- understand information (58 percent), tax advantages for key executives (55 percent), or reduced administrative requirements (53 percent) would make them no more likely to offer plans.

There is a limited correlation between potential motivating circumstances to offer a plan—such as increased business profits, increased tax credits, and increased demand from employees—and the main reasons employers gave for not doing so, including cost, resources, and a lack of employee demand. For example, whether or not respondents cited “cost” as the main barrier, they were no more or less likely to say that an increase in profits or tax advantages for key executives would motivate them to start a plan.

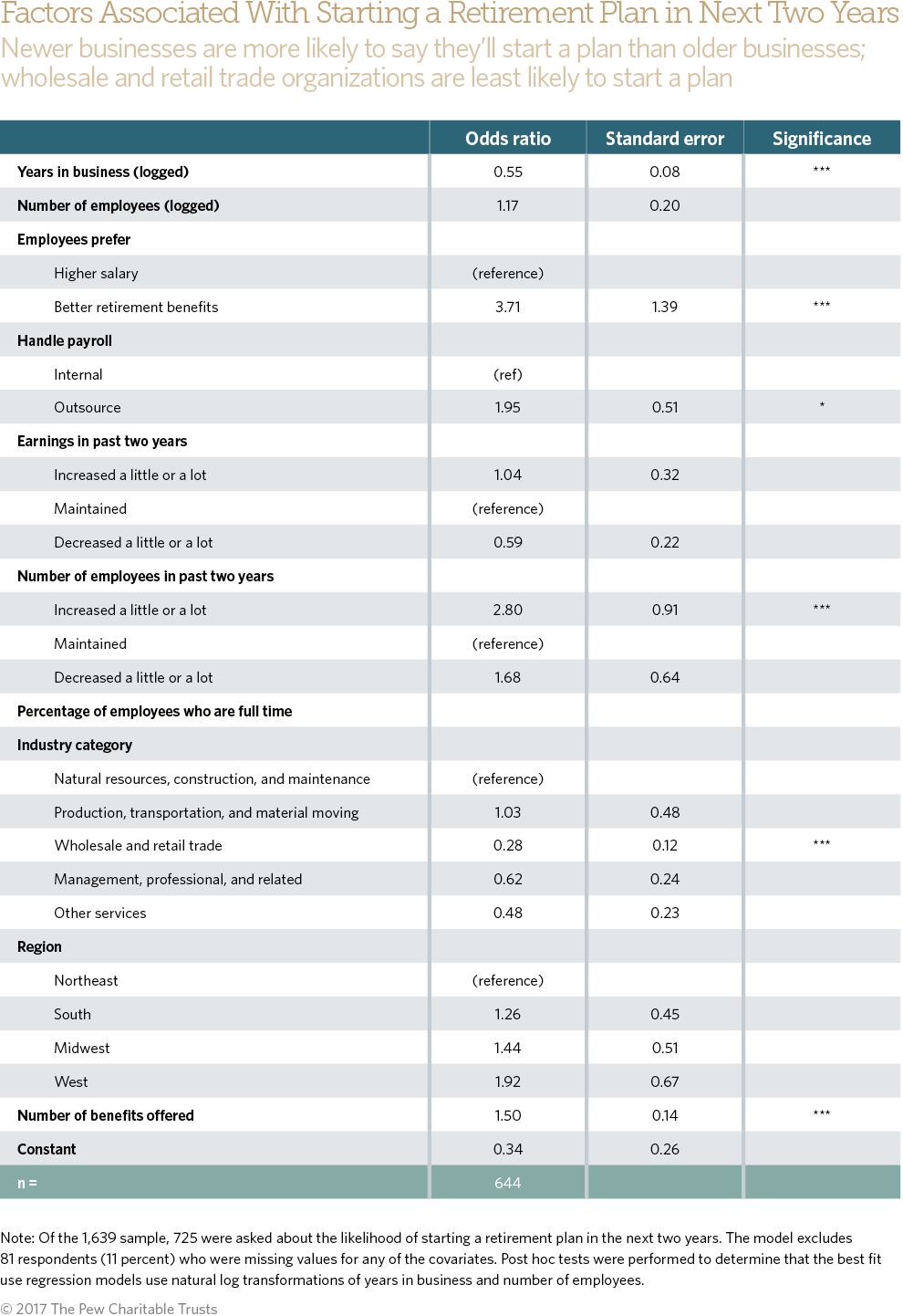

Despite the barriers seen by employers without plans, many said in focus groups that they hoped to provide retirement benefits in the future. Survey respondents, however, seemed unlikely to do so in the near term. When asked if they might start a retirement plan in the next two years, 75 percent said they were no more likely to start one than they had been; just 6 percent said they were much more likely.

In the survey, newer businesses—especially those up to 5 years old—were more likely to say they intend to start a plan than older businesses. Additionally, businesses that have added employees in the previous two years are 2.8 times more likely than those at firms with more stable job numbers to say they will offer a plan. Other potential indicators are whether businesses offer more benefits, whether they outsource their payrolls, and their industry. For each additional benefit offered, businesses are 50 percent more likely to report they are “somewhat” or “much more likely” to offer a plan in the following two years. Those that outsource their payrolls are 95 percent more likely than those who handle their payrolls internally to say they will offer plans. Businesses in wholesale and retail trade are less likely than those in natural resources, construction, and maintenance to say they intend to offer a plan.

But many small and midsize employers appear eager to factor in their workers’ priorities as well. Those who say their employees prefer better retirement benefits over higher pay are more than three times as likely as those who say the reverse to respond that they intend to start a plan. (See Appendix Table 2 for regression results.)

Conclusion

Pew’s analysis finds that leaders of small- to medium-sized businesses who offer retirement plans value them as a way to help their workers save for retirement and as a tool for securing talent. The survey results also indicate that businesses are much more likely to adopt a plan when they are growing and financially stable and when owners perceive that employees are making retirement benefits a priority. However, employers report many significant barriers to offering retirement benefits and putting in place the mechanisms that help employees save.

These findings show that despite the benefits of pro-savings tools, such as automatic enrollment or automatic escalation of contributions, many small employers lack the comfort level or knowledge to take advantage of such tools, or see cost, resources, or a lack of employee demand as reasons not to offer a retirement plan.

Public awareness campaigns targeted at newer, less established businesses could help make clear how these tools work and how they benefit both businesses and employees.

Not all barriers to offering plans, such as business profitability, can be addressed by public policy, but state initiatives could help mitigate other obstacles, such as business leaders’ limited knowledge about various plan options. Policymakers also could boost motivation by providing tax credits to offset the costs of establishing and running a plan or by offering low-cost options, such as a multiple employer plan or a payroll deduction auto-IRA. Policies that effectively educate employees about the necessity of retirement savings also might increase employee demand.14 To be most effective, policy responses will need to address multiple factors confronting employers.

Acknowledgments

This brief benefited from the insights and expertise of Holly Wade, director of research and policy analysis at the National Federation of Independent Business. Although she reviewed the report, neither she nor her organization necessarily endorses its findings or conclusions. Many thanks also to our current and former colleagues who made this work possible.

Methodological appendix

These data were collected by ICF International in the Survey of Decision-Makers at Private Sector Small to Midsize Businesses conducted for The Pew Charitable Trusts. The probability sample is based on the Dun & Bradstreet list of businesses and focuses on private sector small to midsize businesses (five to 250 employees) nationwide. A representative of each business who was knowledgeable about benefits and who had input on benefit-related decisions responded to the survey. ICF International used a stratified survey design to ensure representative national estimates. The strata were the four census regions, whether an enterprise was a goods- producing or service-producing business, and the number of employees (five to 50 and 51 to 250). The survey used computer-assisted telephone interviewing to collect data between April 26 and June 29, 2016.

The sample is split between employers that sponsor a retirement plan (56 percent) and those that do not (44 percent). In terms of staff size, 68 percent have between five and 24 total employees, while the remaining 32 percent have between 25 and 250 total employees. All analyses presented in this report are weighted to match business characteristics based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics.15

Model design

We use logistic regression to examine two dichotomous variables: 1) whether the business offers a retirement plan (Appendix Table 1) and whether the business would start a plan in the next two years (Appendix Table 3). We use a Poisson regression to examine a count of the number of nonretirement benefits a business offers (Appendix Table 2). The models include natural logged transformation of years in businesses and number of employees, whether the employees prefer a higher salary or retirement benefits, whether the payroll was handled internally or outsourced, geographic region, a three-category variable of company earnings in the past two years, a continuous variable of the percentage of the employees who were full time, a five-category industry variable, and whether the business is incorporated. Post hoc tests were performed to determine that the best- fit regression models use natural log transformations of years of business and number of employees. Appendix Table 2 additionally includes a continuous variable of the number of other benefits offered.

Predicted probability (presented in Figures 2a and 2b) of offering a plan is based on logistic regression models of whether a business offers a retirement plan, depending on the age of the firm and the number of employees using Stata’s margins command. Covariates are held at their mean. The association between years in business and offering a plan is significant at p < 0.001. The association between the number of employees and offering a plan is significant at p < 0.001.

When appropriate, we recoded “other” variables into valid categories. We use listwise deletion to handle missing data for up to 15 percent of the sample. Statistical significance is indicated by * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Appendix Table 1

Appendix Table 2

Appendix Table 3

Endnotes

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “How States Are Working to Address the Retirement Savings Challenge: Three Approaches” (July 29, 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2016/07/how-states-are-working-to-address-the-retirement-savings-challenge-three-approaches.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Business Owners’ Perspectives on Workplace Retirement Plans and State Proposals to Boost Savings” (Sept. 7, 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2016/09/business-owners-perspectives-on-workplace-retirement-plans-and-state-proposals-to-boost-savings.

- The survey did not ask about the timing of benefits to be able to clearly identify that employers are more likely to offer health insurance first and then retirement benefits later. Although 18 percent offer a health plan and do not offer a retirement plan, only 9 percent offer a retirement plan and do not offer a health plan. For more information about what factors are related to the number of benefits offered, see Appendix Table 2.

- These probabilities were created using Stata’s margin command.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Having a Retirement Plan Can Depend on Industry or Hours Worked” (November 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2016/11/having-a-retirement-plan-can-depend-on-industry-or-hours-worked.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, Who’s In, Who’s Out: A Look at Access to Employer-Based Retirement Plans and Participation in the States (January 2016), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2016/01/retirement_savings_report_jan16.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Internal Revenue Service, “Choosing a Retirement Plan: Retirement Plan Options,” last modified Jan. 9, 2017, https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/choosing-a-retirement-planretirement-plan-options.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Business Owners’ Perspectives.”

- Ibid.

- David C. John, “The Case for Automatic Enrollment—Stronger Than Ever in 2011,” Benefits Magazine 48, no. 5 (2011): 17–20, http://www. ifebp.org/inforequest/0159990.pdf; Employee Benefit Research Institute, “The Expected Impact of Automatic Escalation of 401(k) Contributions on Retirement Income” EBRI Notes 28, no. 9 (2007): 2–8, https://www.ebri.org/pdf/notespdf/EBRi_Notes_09a-20071.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Business Owners’ Perspectives.”

- There are two types of SIMPLE plans: IRAs and 401(k)s; for simplicity, the survey asks about “SIMPLE plans.”

- Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchelli, “Financial Literacy and Retirement Preparedness: Evidence and Implications for Financial Education,” Business Economics 42, no. 1 (2007): 35–44, doi:10.2145/20070104.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Establishment Characteristics Data Tables,” accessed Oct. 15, 2016, http://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/bds/ data_estab.html.