Let's Protect Critical Ocean Habitat

© Kawika Chetron

© Kawika ChetronA lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus) within coral habitat off the coast of California.

An amazing world lies beneath the ocean surface off the West Coast of the United States. Close to shore kelp forests shelter and nourish young groundfish and also attract an abundance of small, schooling forage fish. Farther out, dozens of species of groundfish live within the rocky reefs, canyons, and deep-water corals and sponges that characterize the relatively narrow continental shelf and its steep slopes. Beyond that lie the deep and mysterious abyssal plains, revealing new discoveries with every exploration.

Many groundfish species, such as sablefish and some types of rockfish, can live for nearly a century and are slow to recover from population declines. In January 2000, following three decades of overfishing and habitat damage caused by fishing gear, the fishery for West Coast groundfish was declared a federal disaster -- requiring that action be taken to restore both the fish population and the fishery. Thanks to bold action by the Pacific Fishery Management Council and regional fishermen to reduce fishing and protect habitat, several stocks have successfully been rebuilt. Yet the condition of many stocks remains fragile.

If we want commercially viable populations of groundfish in the future, we need to protect the places they need to grow and reproduce. Here’s the dilemma: one of the primary methods of catching groundfish involves dragging large nets along or near the ocean floor. This form of fishing can disrupt and damage ecologically sensitive areas. That’s why federal law requires fishery managers to review existing protections every five years and to update these important safeguards when new information comes to light. West Coast fishery managers have just completed a habitat review, which reveals compelling new information about fragile areas of seafloor habitat that should be protected.

The North American Continental Shelf

© Kawika Chetron

© Kawika Chetron

A young China rockfish (Sabastes nebulosus) nestled within

a colony of California hydrocoral (Stylaster californicus) and an unidentified red sponge.

- What it is: The continental shelf is laced with canyons, rocky ridges, and undulating terrain that support a rich network of marine life, anchored by more than ninety managed groundfish stocks.

- Why it’s important: Scientists refer to the coldwater corals found here as “ecosystem engineers” because of their role as a basic building block for fish habitat and their ability to form structures used by invertebrates as well as fish.1

- What needs to be done: Managers should act to protect additional groundfish habitat from adverse impacts from fishing, including newly identified ecologically sensitive areas and recently recovered seafloor.

The Ocean Deep

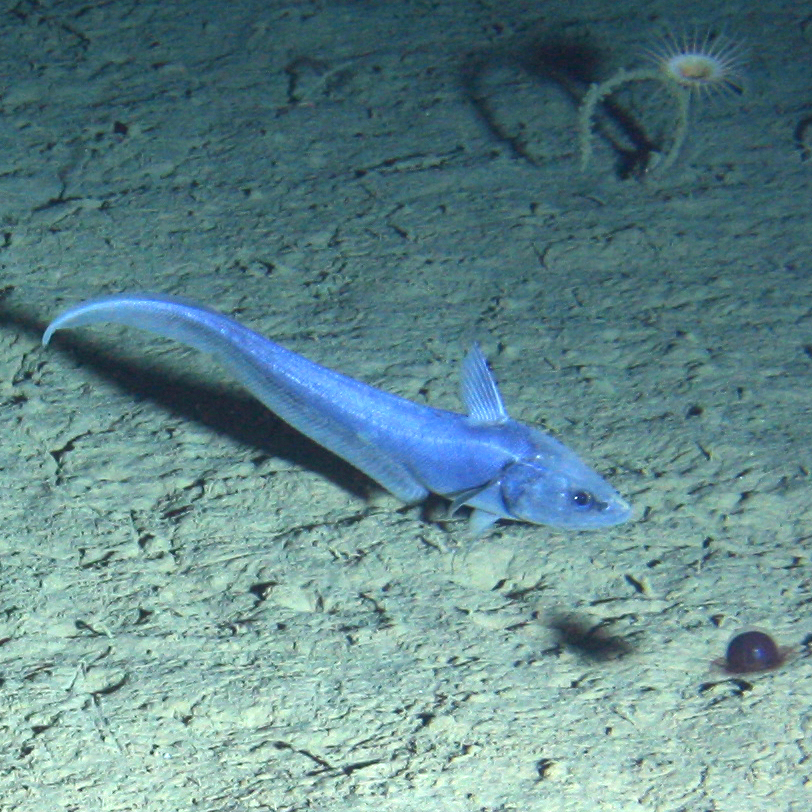

© MBARI

© MBARI

A rattail fish (Grenadier) at the deep-sea research site “Station M,” about 220 kilometers ( 140 miles) off the Central California coast and 4,000 meters below the ocean surface.

- What it is: Seafloor deeper than 3,500 meters below the ocean’s surface.

- Why it’s important: Fragile and poorly understood, this area includes a surprisingly large proportion (about 40 percent) of all federally managed ocean territory out to 200 miles offshore, owing to the West Coast’s relatively narrow continental shelf. New research shows that the deep sea is critically important to people and harbors more than half of all biomass in the world’s oceans.2

- What needs to be done: The Pacific Fishery Management Council should prevent the expansion of bottom trawling into pristine areas of deep water within its jurisdiction.

Take Action

Like the ancient forests on our public lands, a healthy and intact seafloor is critical to the health of the West Coast’s ecosystems and a legacy we should pass to future generations. Ask the Pacific Fishery Management Council to protect ecologically important areas of ocean habitat.

Write the council at [email protected].

Endnotes

1 R. Thurber, A. K. Sweetman, B. E. Narayanaswamy, D. O. B. Jones, J. Ingels, R. L. Hansman. Ecosystem function and services provided by the deep sea. Biogeosciences Discussions, 2013; 10 (11): 18193 DOI: 10.5194/bgd-10-18193-2013

2 Ibid