A Critical Meeting at the Mouth of the Columbia River

Little Fish, Big Deal

It's hard to envision a creature more tightly entwined in Pacific Northwest history, economics, and culture than the salmon coursing through the Columbia River basin.

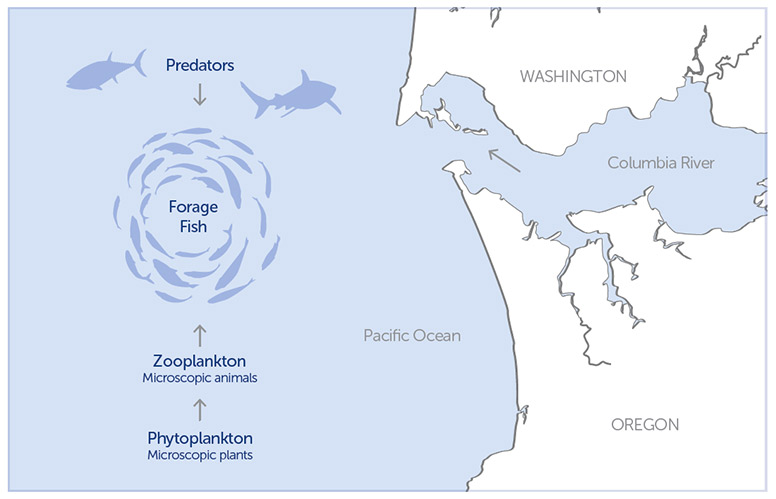

Each year, millions of ocean-bound juvenile salmon migrate through mountain streams, over dams and past cities and farms. As they pour out of a basin covering an area roughly the size of France, their survival depends to a large degree on the small, schooling fish—commonly called forage fish—that congregate where the river meets the sea.

Forage fish play two major roles for salmon

First, schooling fish such as sardines, anchovies, herring, and whitebait smelt provide cover against a gantlet of hungry seabirds, harbor seals, and larger fish that would otherwise devour the bite-size juvenile salmon, just a few inches long, when they arrive at the mouth of the Columbia. In fact, this one point in the salmon journey is crucial in determining the proportion of salmon smolts that will return as spawning adults. It's no coincidence that salmon time the peak of their run for the open ocean in May and June, when forage fish are most abundant.

Then, as salmon mature, forage species become a key food source, accounting for more than half of the diet of chinook salmon.1 The extra calories provided by oil-rich forage fish enable salmon to grow larger, produce stronger eggs, and improve reproductive success.

Unfortunately, forage fish are an undervalued part of a productive ocean

As the principal food source for fish, seabirds, and marine mammals, forage fish are a critical component of the marine ecosystem. But conventional fisheries management does not account for the needs of salmon or the ecosystem as a whole when setting catch limits for forage fish. As a result, salmon may not get the prey fish they need to survive at the critical places and times that they need it most. In 2012, the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, which directs $250 million annually to restore salmon, cited the exceptional importance of the Columbia's estuary and plume, largely due to the presence of forage fish.

These concerns could be exacerbated if pressure increases to satisfy global demand for these species, which are easily netted and processed into fishmeal and oil, most of which goes to feed farm-raised fish. Forage species caught on the West Coast are largely destined for secondary uses, such as sardines exported overseas as bait for industrial longline tuna fishing or as feed for farmed bluefin tuna as far away as Australia. It takes at least 7 pounds of sardines to grow a pound of pen-raised tuna.

There is hope for these important little fish. In 2012, the Pacific Fishery Management Council set an objective to prohibit the expansion of fishing to unmanaged forage species, among them Pacific saury, sand lance and various kinds of smelts, until it can evaluate the impact on the rest of the marine food web, including Columbia River salmon.

Take action

Ask the Pacific Fishery Management Council to help ensure a balanced and productive ocean ecosystem. The council can start by ensuring conservation of forage species such as whitebait smelt, which aren't protected but serve an important role as prey for salmon and other marine wildlife.

After all, these little fish are a big deal!