Protecting America's Arctic from Oil Spills

America's Arctic Ocean is home to some of the Earth's least-disturbed large marine ecosystems. Spectacular wildlife found nowhere else in the United States thrives here, including bowhead whales, walruses, polar bears, and ice seals. Vibrant indigenous communities have lived off the ocean and the land for thousands of years. But warming temperatures and rapidly retreating sea ice are opening these remote waters to oil and gas exploration and vessel traffic. These activities carry the risk of accidents and oil spills that could damage fragile food webs and ruin vital habitat.

Needed: Standards Tough Enough for the Arctic Ocean

U.S. oil spill response standards are not tough enough to ensure that a spill in the remote Arctic Ocean could be cleaned up, especially in broken sea ice. Response standards have not been updated since the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Although the conditions there were far less challenging than those in the Arctic, the Gulf leak took almost three months to shut down, and cleanup crews were able to remove only 25% of the oil spilled—3% by skimming, 5% by burning, and 17% captured at the wellhead. In the extreme, remote Arctic Ocean, hurricane-force winds, 20-foot seas, shifting sea ice, subzero temperatures, and heavy fog can occur at any time of the year. Avoiding a catastrophe in America's Arctic Ocean requires strong safety, prevention, and response standards, including:

Arctic-Class Equipment:

Oil rigs and support vessels should be engineered to safely operate in extreme conditions that may occur during well or relief well drilling or during oil spill cleanup operations.

Seasonal Drilling Restrictions: The best way to ensure that responders have enough time to stop a leak and remove spilled oil using current technology is to limit drilling to periods when ice is not present.

Blowout Control: One of the best new tools for quickly stopping a leaking well—and keeping oil out of the water—is a capping and containment system. However, this system won't work in all cases, and the most reliable way to stop a blowout permanently is to drill a relief well. An Arctic-class capping and containment system and relief-well rig should be positioned in the region and be able to reach a spill site immediately.

Arctic-Certified Oil Spill Response Organizations (OSROs): Oil spill removal organizations are a critical component of response plans, providing workers and equipment certified to clean up oil in specific types of water (river, Great Lakes, ocean, etc.). Yet there is no certification specific to working in Arctic conditions. Teams responding in the Arctic Ocean need Arctic-class equipment and training for a variety of adverse situations.

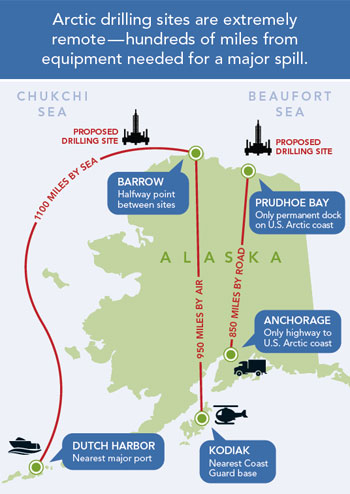

In-situ Burning Equipment and Training Standards: In-situ burning (ISB) is an important tool for Arctic spill response. However, there are no standards for Arctic equipment and training, and these should be established. Essential ISB equipment should be stockpiled in the U.S. Arctic Ocean region for quick response, given the remote location and lack of transportation infrastructure.

Protection of Special Environmental, Cultural, and Economic Places: Indigenous residents consider the Arctic Ocean their garden; it supports important their subsistence way of life and important wildlife habitat. Plans should be in place to protect sensitive areas in case of an oil spill. Protection strategies should be proven to work, especially along the very shallow nearshore and shoreline.

Field Testing of Oil Spill Response Tactics: Arctic oil spill response tactics should be tested to ensure that equipment is deployable and works efficiently in extreme cold, broken ice, and high winds and seas.

Field Testing of Oil Spill Response Tactics: Arctic oil spill response tactics should be tested to ensure that equipment is deployable and works efficiently in extreme cold, broken ice, and high winds and seas.

Public Review of Spill Response Plans: Unlike most federal plans and permits, there is no mandatory public review process for oil spill response plans. The public has the right to review these documents as part of a thorough assessment process.

Challenges to Oil Cleanup in the U.S. Arctic Ocean

Skimmers: Slush ice can clog skimmers used to remove oil from water. Cold temperatures can freeze the hoses used to move the oil to a storage container. Skimmers and hoses can become unusable for hours or days until thawed.

Burning: Because oil has to be thick enough to burn, it cannot be burned if conditions prevent its collection. Although oil can collect in pools of open water when ice is present, burning could be problematic because these openings are hot spots for migrating wildlife such as bowhead whales, belugas, and seabirds.

Boom: Used to collect oil until it is thick enough to be skimmed or burned, boom will fail in waves more than six feet high, wind more than 22 mph, and in small amounts of broken ice.