Protecting Silky Sharks at IATTC

The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) will hold its 82nd annual meeting in La Jolla, California from July 4-8, 2011. The IATTC is one of five Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) established to manage fishing of tuna and tuna-like species. However, with the entry into force of the Antigua Convention in September 2010, the mandate of the IATTC has been updated to include an emphasis on implementing the ecosystem approach and precautionary principle in management decisions. This mandate offers the IATTC a critical opportunity to adequately address bycatch concerns and significantly reduce tuna fishing impacts on the ecosystem and on non-tuna species in the convention area such as sharks.

Reasons to support a prohibition on retention by IATTC fisheries

- Silky sharks are biologically vulnerable to overexploitation

- They are targeted for their fins and also caught as bycatch.

- In the eastern Pacific Ocean, silky sharks are the most commonly caught shark species in the purse seine fishery and are also caught in the longline fishery.1

- While there is little information available on the population status of silky sharks, the data that is available has shown catch is going down. This reduction in catch is most likely due to pressure from fishing.

- Silky sharks are often mislabeled, either grouped as Cacharhinids or labeled as blacktip, since fishermen refer to the silky shark as “punta negra”. As a result, bycatch of this species may be higher than recorded.

Biological vulnerability to overexploitation

- Long gestation period of 12 months.

- Low to moderate population growth rates, in comparison with other shark species.

- Long reproductive periodicity, reproducing every one to two years.

- Low reproductive capacity, with only two to nine pups per litter.

Silky shark fisheries and trade

Silky sharks can be found in oceanic and coastal areas in tropical waters around the globe. They are both targeted and caught as bycatch and are often associated with fish aggregating devices (FADs). Fishing pressure from longline and purse seines targeting tuna and swordfish is high for this species, especially in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Silky shark fins are relatively high-valued and are the third most commonly traded species in the fin trade.2 Between half a million and one and a half million silky sharks are traded annually for their fins.3

Silky sharks can be found in oceanic and coastal areas in tropical waters around the globe. They are both targeted and caught as bycatch and are often associated with fish aggregating devices (FADs). Fishing pressure from longline and purse seines targeting tuna and swordfish is high for this species, especially in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Silky shark fins are relatively high-valued and are the third most commonly traded species in the fin trade.2 Between half a million and one and a half million silky sharks are traded annually for their fins.3

In the eastern Pacific Ocean, silky sharks are the most commonly caught species in the purse seine fishery. They are also commonly caught in the longline fishery. In the IATTC Shark Characteristics Sampling Program in 2000-2001, silky sharks accounted for more than 63 percent of the bycatch.4 Fishermen often refer to silky sharks by the common name “punta negra,” which has led to the misclassification of silky sharks as blacktips. While observers are capable of correctly identifying silky sharks, analysis has shown blacktip sharks in the offshore fishery are actually silky sharks, thus bycatch may be higher than what is recorded.5 Bycatch of silky sharks by purse seine vessels has been found to occur most frequently north of 4°N and west of 100-105°W.6 Catch data shows the bycatch of silky sharks is decreasing in all three purse seine set types, but the floating-object sets have the greatest potential for impacting the sustainability of these sharks.7 Comparisons of catch per set for silky sharks from 1993-2004 suggests these sharks are in decline, thus raising concern for the future survival of this species.8

Conclusion

The IATTC Commission should protect this vulnerable species by prohibiting the retention of silky sharks in all fisheries in the Convention area and requesting the immediate live release of any silky shark.

References

1. Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, “Fishery Status Report 8,” La Jolla, CA, 2010. http://iattc.org/PDFFiles2/FisheryStatusReports/FisheryStatusReport8ENG.pdf>

2. S. Clarke, J.E. Magnusson, D.L. Abercrombie, M. McAllister and M.S. Shivji, “Identification of shark species composition and proportion in the Hong Kong shark fin market using molecular genetics and trade records,” Conservation Biology 20: 201-211 (2006).

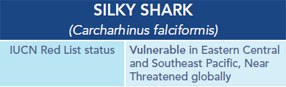

3. R., Bonfil, A. Amorim, C. Anderson, R. Arauz, J. Baum, S.C. Clarke, R.T. Graham, M. Gonzalez, M. Jolón, P.M. Kyne, P. Mancini, F. Márquez, C. Ruíz, and W. Smith. 2007. Carcharhinus falciformis. In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. www.iucnredlist.org> Downloaded on 28 April 2011.

4. M. Román-Verdesoto and M. Orozco-Zöller,“Bycatches of sharks in the tuna purse-seine fishery of the eastern Pacific Ocean reported by observers of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, 1993- 2004,” Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission Data Report 11, La Jolla, CA, 2005. http://www.iattc.org/PDFFiles2/DataReports/Data-Report-11.pdf>

5. M. Román-Verdesoto and M. Orozco-Zöller, “Bycatches of sharks in the tuna purse-seine fishery of the eastern Pacific Ocean reported by observers of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, 1993-2004,” Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission Data Report 11, La Jolla, CA, 2005. http://www.iattc.org/PDFFiles2/DataReports/Data-Report-11.pdf>

6. Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, “Fishery Status Report 8,” La Jolla, CA, 2010. http://iattc.org/PDFFiles2/FisheryStatusReports/FisheryStatusReport8ENG.pdf>

7. Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, “Fishery Status Report 8,” La Jolla, CA, 2010. http://iattc.org/PDFFiles2/FisheryStatusReports/FisheryStatusReport8ENG.pdf>

8. M. Román-Verdesoto and M. Orozco-Zöller, “Bycatches of sharks in the tuna purse-seine fishery of the eastern Pacific Ocean reported by observers of the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, 1993-2004,” Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission Data Report 11, La Jolla, CA, 2005. http://www.iattc.org/PDFFiles2/DataReports/Data-Report-11.pdf>