New York’s Housing Shortage Pushes Up Rents and Homelessness

Some jurisdictions have added housing and kept rent growth low

Housing costs have soared in much of the United States over the past decade. In 2022, the median rent-to-income ratio reached 30% for the first time, with a record-high number of Americans exceeding that threshold. Research has found that a severe housing shortage is to blame for rising costs, with restrictive zoning practices limiting the construction of new homes in high-demand, job-rich areas. This shortage is acute in much of New York state, where high housing costs have pushed many families to leave the New York City metro area in search of lower-cost housing. In this analysis, The Pew Charitable Trusts finds that rent growth in New York state has been lowest in jurisdictions that have enabled more housing to be built. It also finds that New York City has much higher homelessness rates than other major cities where rents are lower.

Housing construction in New York City and its suburbs has lagged far behind that of other major cities and their suburbs, resulting in low housing availability and a vacancy rate of just 3%. New York City’s housing stock has only increased 4% since 2010, not nearly enough to keep up with its 22% increase in jobs. And from 2017 to 2021, New York City permitted 13 homes for every 1,000 residents in 2017, while Boston added 28, Washington, D.C., added 43, and Seattle added 67. New York City’s suburbs also contributed to the lack of available housing in the region. For example, Nassau County and Suffolk County on Long Island permitted just 5 and 3 homes per 1,000 residents, respectively, during this period. In contrast, the Boston suburbs of Middlesex County and Norfolk County added 14 and 15 homes, respectively, and the Washington, D.C., suburbs of Arlington County and Loudoun County added 45 and 40 homes per 1,000 residents, respectively.

New York’s lack of building doesn’t represent weak demand for housing, because its low vacancy rates and high rents indicate strong demand for homes. Instead, rigid local regulations and cumbersome permitting processes have made building difficult, especially for lower-cost homes such as apartments, houses on small lots, units without off-street parking, and accessory dwelling units, such as basement, garage, or backyard apartments. Prior Pew research found that jurisdictions that updated their zoning policies to allow these types of homes had added more housing and contained rent growth.

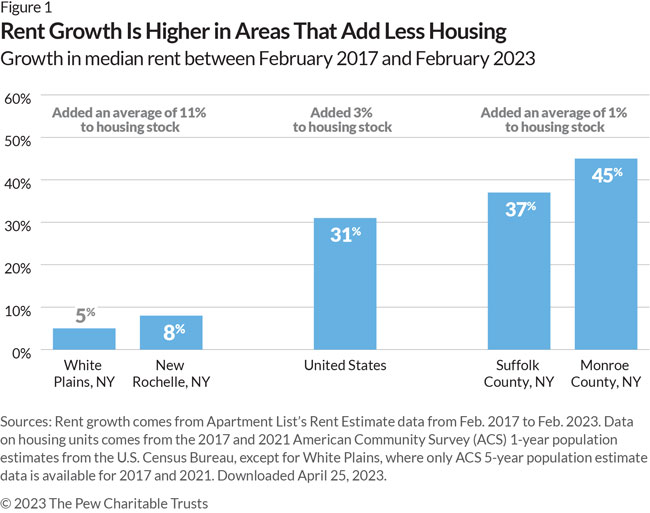

In New York state, Apartment List data shows that the two places with the slowest rent growth from February 2017 to February 2023 were New Rochelle (8%) and White Plains (5%), while those with the fastest rent growth were Suffolk County (37%) on Long Island and Monroe County (45%), which encompasses Rochester. New Rochelle and White Plains added an average of 11% to their housing stock from 2017 to 2021, while Suffolk and Monroe Counties added an average of only 1% to their housing stock. Furthermore, New Rochelle and White Plains saw low rent growth despite averaging a 12% increase in households versus 6% in Suffolk and Monroe counties.

These examples from New York are consistent with numerous studies that have found that adding new housing helps hold down rent growth, even when new units do not have explicit affordability requirements. New Rochelle and White Plains mainly added market-rate apartments to their housing stock and still experienced lower rent growth than places that failed to add new housing. However, even as New Rochelle and White Plains have added substantial housing, other jurisdictions have not, and regional affordability overall has worsened. The fact that motivated localities cannot hold down rent growth beyond their borders demonstrates why achieving housing affordability will likely require states to act. Many states are considering whether to allow some lower-cost forms of housing in most residential areas or near transit and in commercial areas to improve affordability.

Even as New Rochelle and White Plains added homes and slowed rent growth, home values in those places continued to rise, according to Zillow data, albeit at a slower rate than the U.S. overall. Other jurisdictions that have added housing and slowed rent growth, such as Minneapolis and Portland, Oregon, have also seen home values rise but more slowly than the U.S. overall. These experiences indicate that even rapid expansions in housing production are unlikely to cause home prices to fall.

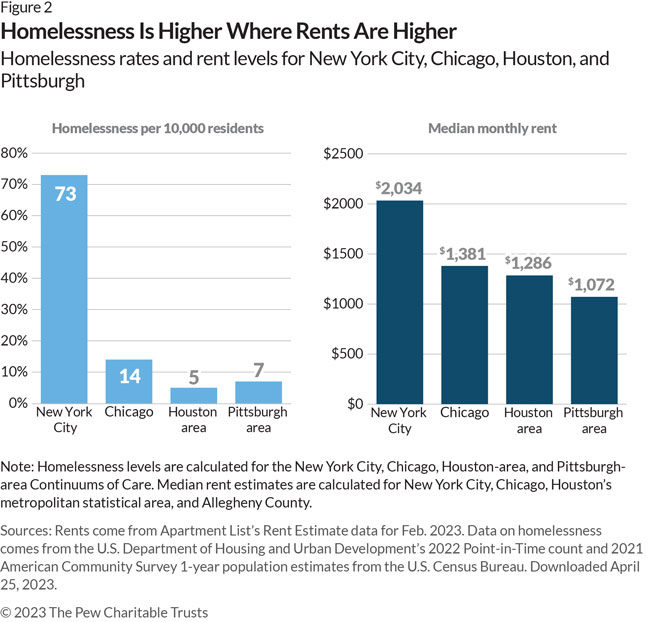

In addition to slowing rent growth, a large body of research has demonstrated that adding more housing can help reduce homelessness. New York jurisdictions have especially restrictive zoning laws, and the state has the country’s fifth-highest rate of homelessness. The problem is acute in New York City, where 73 of every 10,000 people lack a home. Examples of other major cities with lower homelessness levels are Chicago (14), Pittsburgh (7), and Houston (5).Research has found that differences in homelessness rates between cities are primarily driven by rent differences, not other factors. Although New York City has spent heavily to alleviate homelessness, high rents resulting from a continued housing shortage have limited the effectiveness of those efforts.

As debates continue over whether to modernize zoning codes to allow more housing, the experiences of New York and several of its jurisdictions demonstrate the benefits of doing so. Evidence shows that allowing more housing, whether subsidized or not, can slow the growth of rents and reduce homelessness.

Alex Horowitz is a director and Adam Staveski is a senior associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.

Spotlight on Mental Health

Pathways to Homeownership: Housing in America

Rigid Zoning Rules Are Helping to Drive Up Rents in Colorado

More Flexible Zoning Helps Contain Rising Rents