Investments, Costly Savings Program Drive $3.3B Shortfall in Dallas Pension System

Pew analysis details city’s unfunded liabilities

© iStock

Dallas’ public safety pension fund had more than $3.3 billion in unfunded liabilities as of 2015. While recent changes passed by the state Legislature reduced the city’s liabilities by about $1 billion, the fund still has less than half of the assets needed to pay promised benefits. This shortfall was driven largely by low investment returns and the high cost of a supplemental savings benefit program, according to a recent analysis by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Pew examined the Dallas Police and Fire Pension System (DPFP) at the request of the city and shared its findings with the city manager in May. The analysis found that the system had enough assets on hand to pay for only 45 percent—about $2.7 billion—of the retirement benefits promised to workers as of 2015.

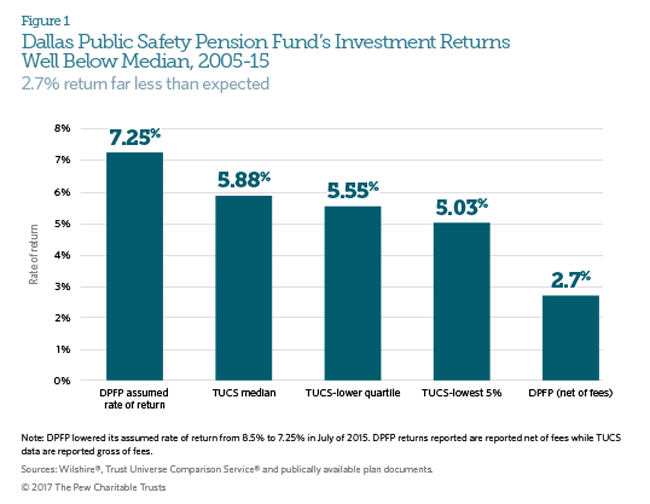

Pew estimates that lower-than-expected—and below-average—investment returns on pension assets over the past decade accounted for at least $700 million of these unfunded liabilities. The DPFP was the lowest performing of more than 100 city and state pension funds that Pew tracks. According to the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service (TUCS), the system’s 10-year investment performance of 2.7 percent through 2015 was well below the median return of 5.88 percent over the same period. The Dallas plan reports its results net of fees, while the TUCS numbers are gross of fees. Still, even if adjusted to account for investment management fees—Pew’s analysis indicates average fee levels of about 35 basis points for public plans—the numbers clearly show the weaker performance of the DPFP investments.

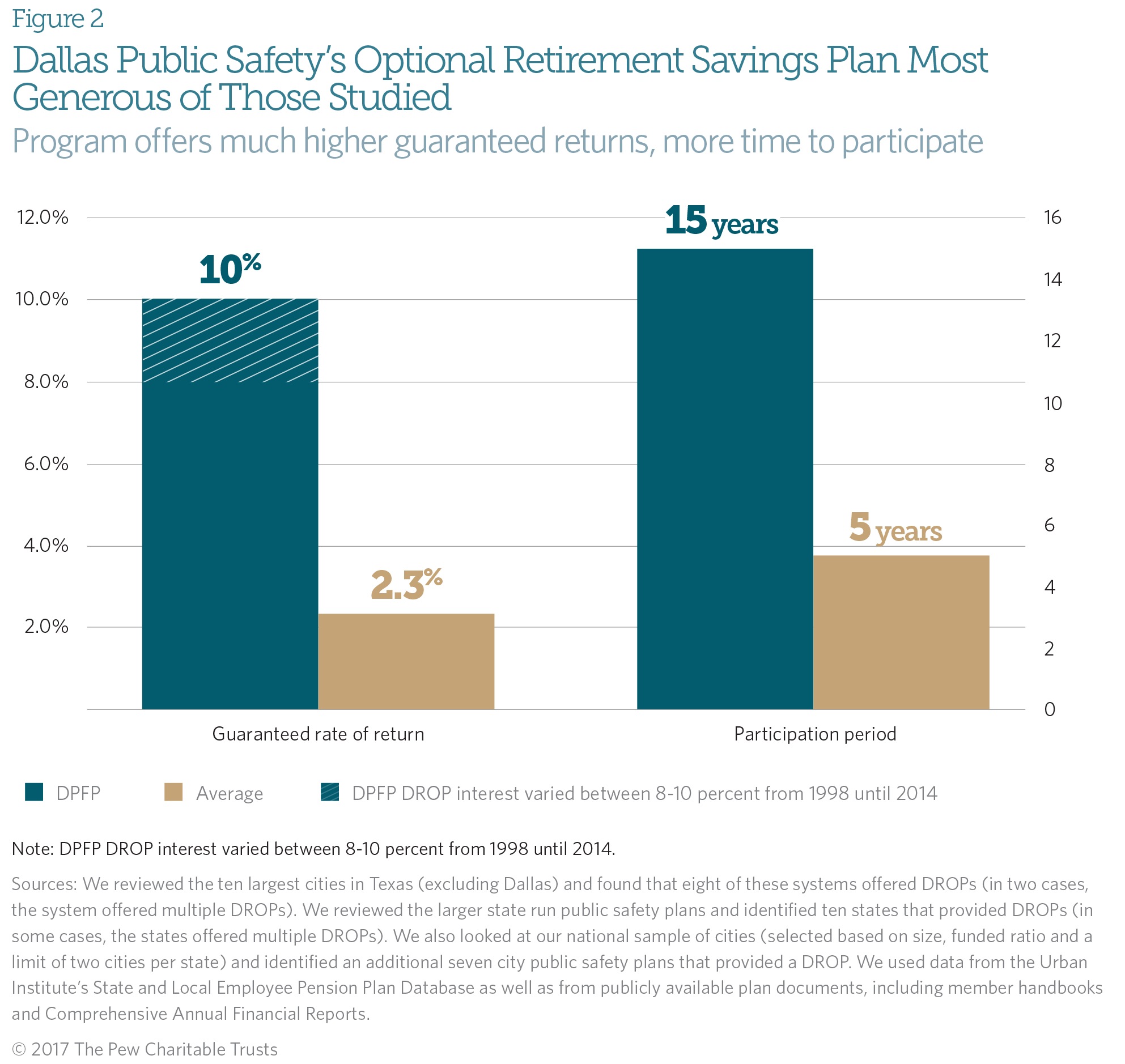

Differences between the interest credited to the savings accounts for those in the system’s Deferred Retirement Option Plan (DROP) and the amount actually earned by the fund represented another $600 million to $700 million in unfunded liabilities as of 2015. Many cities offer DROPs—supplemental savings plans for employees willing to postpone retirement—as an incentive to retain experienced workers in critical areas. Those with the accounts were guaranteed returns of up to 10 percent a year, but fund investments typically earned far less.

The Pew analysis, which included comparisons to 28 DROP savings accounts around the country, found that DPFP’s was much more generous, on average, than any other plan studied. The average interest rate guaranteed by other DROPs was about 2 percent, although half offered no guarantee. Additionally, the unlimited participation period for the Dallas DROP was unusual—most programs are limited to about five years. Recent changes to the DPFP DROP program have reduced participation periods, with a cap of 10 years, and lowered the interest on employee DROP accounts.

The analysis found that the burden created by lower-than-expected investment returns and the structure of the DROP program will mean $50 million or more a year in additional costs to the city for decades as it pays off the unfunded liabilities.

And that means that paying down these liabilities will have a significant impact on the city’s budget. In 2014, Dallas’ pension costs for all city plans were about 6.7 percent of total city revenue. That ranked the city 16th among the 34 large cities that Pew tracks. Under reforms to state law that take effect Sept. 1, the city will raise its payments to the DPFP to over $150 million annually. Even with these increases and the other reforms, the DPFP is not expected to be fully funded until 2061, assuming that the plan meets its investment targets going forward.

In addition to improving funding for the DPFP, state policymakers sought in the reform legislation to strengthen pension governance more generally and provide a mechanism to recoup excessive benefit payments. The law requires that public representation on the plan’s board of trustees expand and that most board members have relevant expertise. It also mandates that board members execute their duties as fiduciaries, creating a legal duty to exercise “great care” in managing plan assets. And the reforms give the board the authority to decrease benefits if it determines that excessive funds were paid or credited to a beneficiary.

Although poor investment performance and the DROP structure were major contributors to the financial issues facing the Dallas system, the recently adopted reforms to both funding and governance should help to shore up the city’s unfunded liability, improve plan management, and place a greater focus on overall plan sustainability. However, it is not clear that they are sufficient to put the plan on a path to full funding within a reasonable time frame or offer a policy to manage future risk and uncertainty.

Greg Mennis, David Draine, and Tim Dawson are with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public sector retirement systems project.