North Water Polynya Commission Visits Greenland and Nunavut

Inuit communities urge protection of biologically rich waters

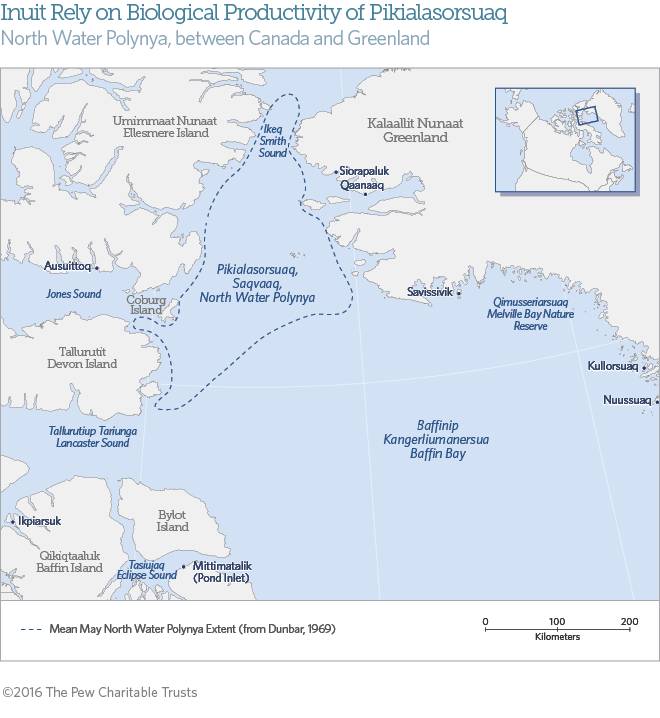

Almost the entire village of Siorapaluk on Greenland’s northwestern coast turned out to meet with a three-member Inuit commission that came to the community seeking advice about how best to manage and protect the nearby North Water polynya for future generations. Called Pikialasorsuaq, or “Great Upwelling,” by Inuit, this Arctic polynya is a biologically productive area of open water surrounded by ice at the northern end of Baffin Bay between Greenland and Ellesmere Island in Canada.

“Siorapaluk is perched right on the North Water and uses it very directly,” said Chris Debicki, Nunavut projects director for Oceans North Canada, who traveled with the Pikialasorsuaq commission. “Harvesting wildlife in those waters is part of their identity and an important nutritional source.”

The special commission, set up by the Inuit Circumpolar Council, chartered a boat and braved rough seas on a two-week journey to visit six remote villages along the Greenland coast in late August and early September.

“There are few runways in these villages, so we chartered an old research vessel,” Debicki said. “I’m pretty proud of my iron stomach, but it was certainly tested on this trip.”

In April, the commission held hearings in the Nunavut communities of Pond Inlet and Grise Fiord. Inuit in Greenland and Canada want to work together to manage the North Water polynya and monitor the impact of climate change on the region, Debicki said. They also want to be able to travel back and forth more freely across the ice bridge at the top of the approximately 85,000-square-kilometre (32,700-square-mile) polynya that connects Greenland and Ellesmere Island, he said. Inuit from Nunavut migrated to Greenland along that route centuries ago, and hunters from both countries still rely on it when harvesting whales and seals.

“There was a lot of concern that this biologically productive region be protected from seismic testing and industrial fishing,” Debicki said, adding that communities are also worried about the impact of increased shipping, tourism, and other commercial activities.

North Water polynya commissioners arrive at high tide in Qaanaaq, Greenland, for a community hearing as a supply ship unloads in the background.

© Chris Debicki

Many migratory species, from narwhal and beluga to walruses and seabirds, spend winters in the polynya and depend on its plankton bloom for food.

The commissioners—Okalik Eegeesiak, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council; Eva Aariak, former premier of Nunavut; and Kuupik Kleist, former Greenland premier—plan to issue a report with recommendations for oversight of the polynya to governments in Greenland and Canada by the end of the year.

The commission was created after representatives from Inuit communities located near the North Water polynya attended a two-day workshop in Nuuk, Greenland, in September 2013 to discuss strategies for preserving the region.

Scott Highleyman oversees marine campaigns in Canada, Greenland, and international waters that promote science and community-based conservation of the Arctic Ocean and the welfare of indigenous residents who rely on this ecosystem.