Listen to an Expert Discussion of Bering Strait Vessel Traffic

As Arctic sea ice melts, ship traffic through the international waters of the Bering Strait has increased, heightening the risk of oil spills and other accidents. On Aug. 15, I moderated a Pew webinar with Roger Rufe, former vice admiral of the U.S. Coast Guard, and Austin Ahmasuk, an advocate with Kawerak Inc., a tribal nonprofit based in Nome, Alaska, that advocates for Alaska Native communities, to discuss the cultural, ecological, and economic stakes of increased vessel traffic in this sensitive Arctic region. Both speakers emphasized that more must be done to protect the environment from oil spills, pollution, and other accidents.

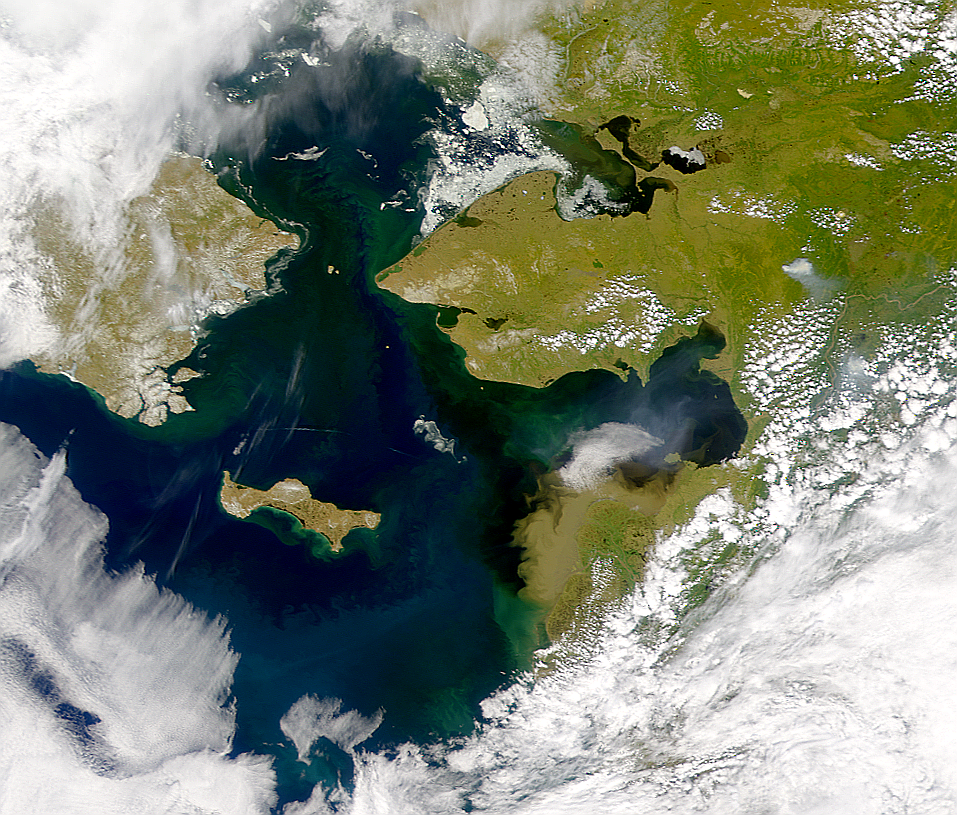

© Provided by the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE

© Provided by the SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE The international waters of the Bering Strait between Russia and the United States are a gateway to the Arctic Ocean.

The Bering Strait, about 44 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point, is the Pacific gateway to the Arctic Ocean for both the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage. As evidence of the growing interest in this region, the first luxury cruise ship to travel through the strait and the Northwest Passage—the Crystal Serenity—is making a 32-day voyage from Seward, Alaska, to New York City this month with more than 1,000 people aboard.

In the context of this rising commercial attention, Rufe said that ship traffic through the Bering Strait has doubled in the past three to four years to about 500 or so transits annually and will only increase because it reduces interocean travel time. But vessels using the route must navigate hazardous conditions with limited nautical charts, poor communication systems, and inadequate emergency response capabilities.

Next month the U.S. Coast Guard is expected to release its two-year Port Access Route Study (PARS) of the strait that will recommend safe routes and identify sensitive areas to be avoided based on recent depth soundings of the area. In international waters such as the Bering Strait, however, formal rules will require action by the International Marine Organization (IMO).

Rufe also discussed the IMO’s Polar Code, which will take effect in January 2017. The code will provide standards for ship safety, restrict some discharges from ships, and adopt construction standards for vessels operating in polar regions, among other measures. He added that more must be done, though, to protect the Arctic environment.

For example, he said that an oil spill in this region would be “pretty catastrophic” to the fragile ecosystem because of the vast distances between many transit routes and emergency response and the lack of infrastructure in nearby ports. He said that a deep-water port is needed to provide adequate capacity for rescue operations and oil spill cleanup. If a ship the size of the Crystal Serenity luxury liner ran into trouble, a rescue operation would be “very, very difficult,” he said.

The Polar Code is a good start, but it and other international laws still have gaps. For instance, they allow vessels to discharge harmful materials, including sewage, greywater, and ballast water, in the region. Stronger standards of care, such as vessel routing measures, improved safety communication systems, emergency prevention and preparedness, and consistent and meaningful community involvement, are essential to protect the region.

Ahmasuk pointed out that coastal communities are always the first responders when accidents happen in the Bering Strait, but they lack adequate equipment and infrastructure. He stressed that local communities want to partner with agencies and organization that can help address these needs and ensure that the marine habitat, which provides food security for Alaska Natives and is part of their traditional way of living, is protected as commercial shipping increases.

Henry Huntington is a senior officer and science director for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Arctic programs.