In Dental Health, Three Areas of Improving Access

A look back at 2015

Millions of Americans suffer from preventable dental disease. Many struggle to access dental care, particularly low-income families, people of color, seniors, and those living in areas with a shortage of dentists. In addition to negatively affecting overall health and well-being, lack of access to care also puts a significant strain on state and federal health care spending. When patients do not have access to a dentist, their oral health care needs often go unaddressed until the pain becomes so severe they seek relief in an emergency room. The American Dental Association estimates that in 2012, the U.S. health care system spent $1.6 billion on dental-related emergency room visits.1

Three evidence-based policy solutions to these oral health access problems gained ground at the local, state, and national levels in 2015: workforce innovation, school-based sealant programs, and community water fluoridation.

Expanding the dental team to increase access

In August, the Commission on Dental Accreditation—the accrediting body for academic dental programs—voted to implement educational standards for dental therapy training. Dental therapists are midlevel providers similar to physician assistants. They can help dentists build their practices and expand access to oral health care by providing preventive and routine restorative care, such as filling cavities. Pew has previously noted eight reasons these standards for dental therapy are important.

To date, at least 10 states have considered legislation that would allow dentists to hire midlevel providers. Legislation is pending in Massachusetts, and the Oregon Health Authority is considering a pilot program that would improve access to care for tribal communities. Dentists have successfully worked for years with midlevel providers in Alaska and Minnesota to expand access to care. Maine is the latest state to allow dentists to hire these providers, authorizing the practice in 2014.

In 2015, the National Caucus of Native American State Legislators and National Black Caucus of State Legislators voted to endorse dental therapy or related programs. These groups join the American Dental Hygienists’ Association, American Public Health Association, the National Dental Association, and the National Foundation for Women Legislators, which already passed similar resolutions.

Some states make progress, but many lag on dental sealants

Dental sealants—plastic coatings placed on the chewing surfaces of teeth—can reduce decay by 80 percent in the two years after placement and continue to be effective for nearly five years.2 For low-income children, who have higher rates of decay and are less likely than their higher-income peers to get care,3 school-based sealant programs are critical to receiving preventive dental care. School-based or school-linked dental sealant programs that target low-income children have been found to reduce tooth decay by an average of 60 percent over five years.4

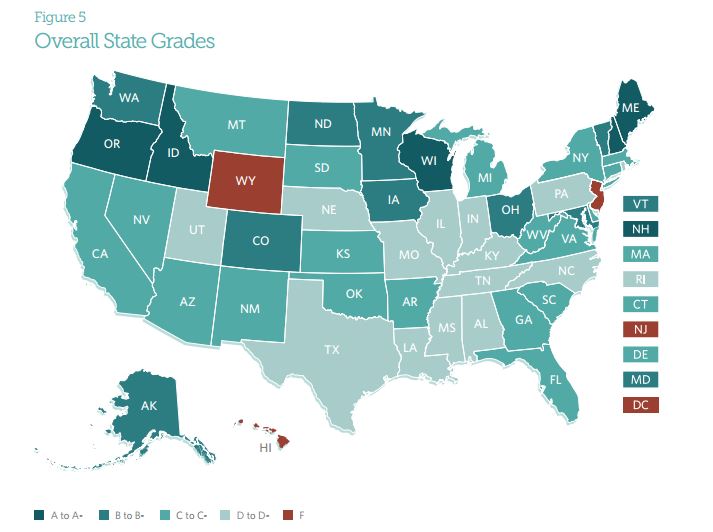

Pew released a report in April evaluating all 50 states and the District of Columbia on their performance in sealing the teeth of low-income children, a follow-up to a similar report from 2013. Pew graded the states and the District on four benchmarks that reflect the reach, efficiency, and effectiveness of their school-based sealant programs. Although several states have made improvements over the past two years, the study found that most states are not meeting national goals and are not enacting policies to provide sealants to low-income and at-risk children. See how each state performed here.

Our 50-state analysis assigns each state a letter grade that reflects the quality of their policies and practices around dental sealants.

This year, Arizona, Illinois, and Utah removed a major barrier to school-based sealant programs by allowing more hygienists to apply sealants in schools without a prior exam. State rules that require a dentist to examine children before a hygienist can apply sealants make these programs more cumbersome and expensive. The action taken in these three states is tremendous progress.

Community water fluoridation advocacy continues

Community water fluoridation is one of the most effective and least expensive strategies for preventing tooth decay, the most common chronic disease among children in the United States. This year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services finalized standards for the recommended level of fluoride in drinking water to a single level: 0.7 milligrams per liter.

At the state level, New York appropriated funds this year to finance fluoridation startup and maintenance costs. It also improved transparency by requiring localities that discontinue water fluoridation to issue public notices and include a summary of the considerations and justification as well as alternative fluoride options available.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, through management of the Campaign for Dental Health, will continue to educate and advocate for community water fluoridation at the local, state, and national levels. Its contributions have already demonstrated meaningful progress toward improving oral health.

Stay up to date on oral health research and policy throughout the year by signing up for Pew’s children’s dental campaign newsletter.

Jane Koppelman is research director for children’s dental policy at The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Kristen Mizzi Angelone manages state campaigns for children’s dental policy.

Andrew Peters oversees state campaigns on dental sealant policies.

Endnotes

- American Dental Association, Health Policy Institute, “Emergency Department Use for Dental Conditions Continues to Increase” (2015), http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/ HPIBrief_0415_2.ashx.

- Susan O. Griffin et al., “Use of Dental Care and Effective Preventive Services in Preventing Tooth Decay Among U.S. Children and Adolescents—Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, United States, 2003-2009, and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005-2010,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Sept. 12, 2014), http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6302a9.htm?s_cid=su6302a9_w; and Anneli Ahovuo-Saloranta et al., “Sealants for Preventing Dental Decay in the Permanent Teeth,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3 (2013), doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001830.pub4.

- Bruce A. Dye et al., “Trends in Oral Health Status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004,” National Center for Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics 11, no. 248 (2007): 23, Table 10, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_248.pdf.

- Benedict I. Truman et al., “Reviews of Evidence on Interventions to Prevent Dental Caries, Oral and Pharyngeal Cancers, and Sports-Related Craniofacial Injuries,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 23, 1 Suppl. (2002): 21–54, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12091093.