Balancing Renewable Energy Development and Land Conservation in the California Desert

The California desert is a place of grand beauty, rich wildlife, and remote landscapes perfect for adventures. But in recent years, these wide open spaces have been targeted for development by the burgeoning renewable energy industry. To meet California’s ambitious goal of generating at least one-third of its energy from renewable sources by 2020, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the state have released a draft of the land use plan for the area that aims to strike a balance between protecting important desert lands for conservation and fast-tracking other areas for development.

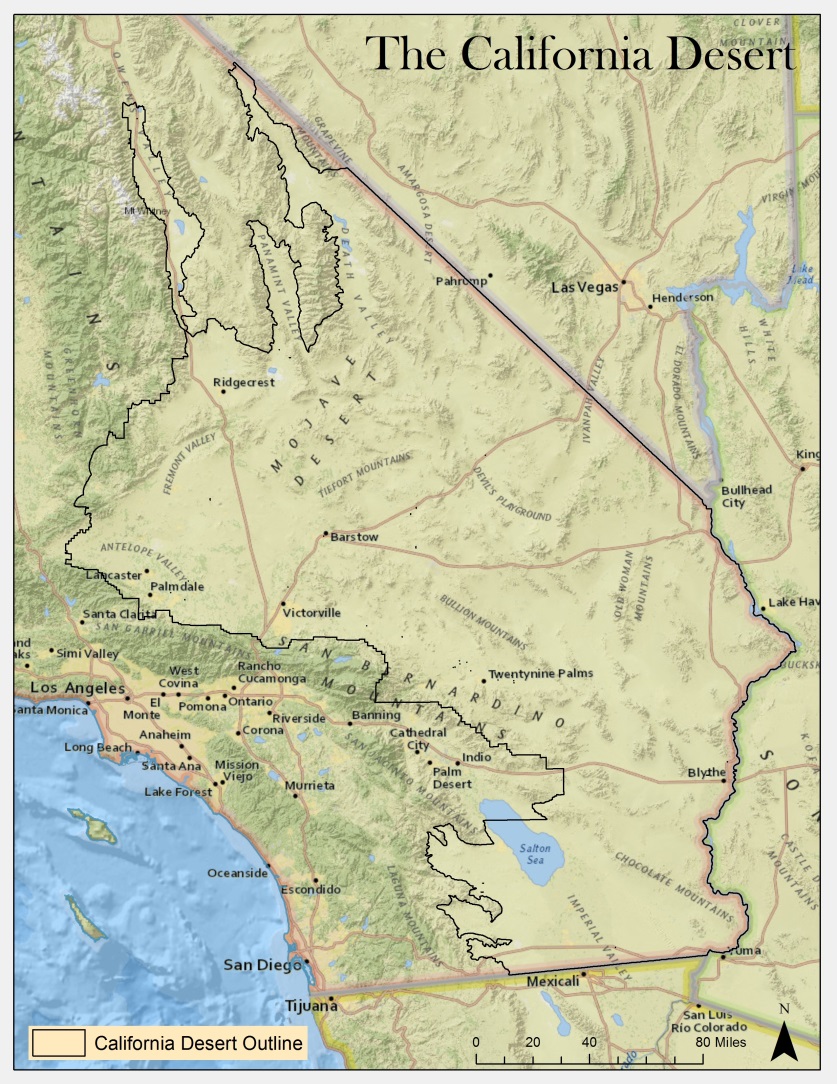

The desert region stretches 350 miles from Owens Valley to El Centro and offers recreational, historical, and cultural attractions. As one of the largest remaining intact desert landscapes in the United States, it could potentially host large solar energy generation facilities capable of contributing to California’s energy goal.

Although this energy development is important, protecting the most wild places in the region for future generations is also vital.

You have a chance to influence the agency’s decision by sending comments that calls on the importance of protecting the desert’s wilderness landscapes.

Learn more about these majestic lands, and why they should be safeguarded. And please make your voice heard through signing your name to the action alert here.

Snapshots from the California desert

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMThe Silurian Valley is a pristine desert landscape south of Death Valley National Park and north of Interstate 15. Largely managed by BLM, the valley and surrounding mountain ranges possess extensive wilderness characteristics, despite not being formally protected. The agency is considering whether the Silurian Valley should be conserved for its wildlife and wilderness values or designated as a renewable energy development area.

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMThe Kingston Range, framed above by the desert oasis Grimshaw Lake, is a massive desert mountain complex north of Interstate 15 that is home to rare desert bighorn sheep and mountain lions, and offers endless opportunities for backcountry adventure. BLM is proposing to add currently unprotected public lands to its reserve area, although the northern viewshed near the Nevada border would be developed under the agency’s draft plan.

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMThe Cadiz Valley and Iron Mountains, 50 miles east of Twentynine Palms, constitute the largest unprotected roadless area in California. Adventurers can walk almost 30 miles from north to south among sand dunes and dry desert mountains without crossing a road. BLM has acknowledged the importance of this special place and does not plan to allow development here.

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMIn the Whipple Mountains, southwest of Lake Havasu City, exists the only population of iconic saguaro cactus in California. Although the area is an extremely arid desert environment, it hosts robust populations of desert bighorn sheep, mule deer, and other wildlife. The northern portion of the range remains unprotected under the BLM’s plan for conservation and renewable energy development.

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMThe Dos Palmas Preserve, managed by BLM, is tucked between the Orocopia Mountains Wilderness and the Salton Sea, southeast of the town of Mecca. As a rare freshwater oasis, this unique collection of palm trees and marsh habitat supports a number of migrating and resident bird species, including the endangered Yuma clapper rail, snowy egret, and American avocet. Visitors from near and far seek out this shady, cool environment for hiking and wildlife viewing.

Bob Wick/BLM

Bob Wick/BLMThe eerie Trona Pinnacles landform is evocative of the California desert’s prehistoric era. Located 20 miles east of Ridgecrest, these spires of salt were formed from deposits of a vast inland sea more than 10,000 years ago. The area was designated as a National Natural Landmark in 1968.