Canada’s Northwest Territories: Protecting the 'Land of the Ancestors'

A First Nations aboriginal community takes lead role in planned boreal forest park

©2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

©2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

LUTSEL K’E, Northwest Territories—Alizette Lockhart sits at a wooden picnic table, clutching a sturdy sewing needle in one hand and a bundle of smooth leather in the other.

It’s a bright summer afternoon on the East Arm of Great Slave Lake in Canada’s Northwest Territories, a place so remote that it is accessible only by plane or boat.

Lockhart and about a dozen other members of the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation have set up a moose hide tanning camp here on the shores of the lake, practicing an aboriginal tradition that sustained their ancestors for generations.

© 2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

© 2014 The Pew Charitable TrustsAlizette Lockhart prepares moose hide leather for smoking as part of an aboriginal hide tanning tradition in Canada's Northwest Territories. Lockhart and other members of the Lutsel K'e Dene First Nation established a tanning camp in June 2014 on the shores of Great Slave Lake.

All around, there is activity.

A few feet from Lockhart’s table, Pete Enzoe stretches a fleshed moose hide over a large timber frame. On a nearby hillside, Madeline Catholique, a Dene woman in her 80s, methodically scrapes another hide, pausing only occasionally to wipe her brow and take a sip from a cup of hot coffee.

Tanning moose hides is a days-long, labor-intensive process, one that in the past was vital to the survival of the Dene people during the long, cold winters in Canada’s North. Moose hide was a staple for jackets, moccasin slippers, gloves, and other clothing.

Lockhart offers a visitor a brief primer on her work, the final stage before the leather is ready.

First, she says, pieces of the hide are sewn together. Then it is smoked for several hours to ensure that the finished leather can withstand harsh weather. Finally, the hide is aired out.

“Every part of the animal is used,” Lockhart explains, gesturing behind herself to a fire where slabs of moose, caribou, and porcupine meat are being cured into jerky. “We never throw anything away.”

© 2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

© 2014 The Pew Charitable TrustsLutsel K’e resident Pete Enzoe stretches a moose hide at a traditional Dene tanning camp on the shores of Great Slave Lake.

It’s a conservation ethic that runs strong among the residents of Lutsel K’e, a village of about 300 people about 115 miles east of Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories.

The Lutsel K’e Dene have been stewards of their traditional lands in Canada’s boreal forest region for centuries. Today, they are at the forefront of efforts to ensure that their historical knowledge of the land guides environmental protection and development practices in a region rich in both ecological diversity and mineral resources.

The centerpiece of that conservation plan is Thaidene Nene—or "land of the ancestors"—a proposed Canadian national park reserve that would cover 7.4 million acres in the heart of the Lutsel K’e Dene homeland. The planned park is so large that it stretches well north of the tree line of the boreal forest region, sprawling deep into the Canadian tundra.

Thaidene Nene sustains large herds of migratory caribou and a diverse array of other wildlife: muskoxen, grizzly bears, wolves, lynx, moose, mink, and large populations of waterfowl and migratory songbirds. It includes parts of Great Slave Lake that have North America’s deepest freshwater reserves. And it is a land of legends for the Lutsel K’e Dene, a place where their cultural foundations were laid.

In 2013, the Lutsel K’e initialled a framework agreement with Canada’s federal government to jointly manage the park, a draft deal that recognizes Dene authority and would ensure that traditional cultural and environmental practices inform its operations.

The Lutsel K’e Dene, the Canadian government, and the government of the Northwest Territories are negotiating final boundaries and shared responsibilities. The proposed area of the park is being temporarily protected from development while the deal is being finalized.

In June, leaders of the community outlined their vision for land stewardship to members of the Boreal Leadership Council.

The council, which is supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts, is a decade-old Canadian organization composed of conservation groups, First Nations, investment firms, and resource industry companies that advocate a balance between conservation and sustainable development in the boreal forest region.

Council members traveled to Lutsel K’e aboard a chartered de Havilland Dash 8. The 35-minute flight from Yellowknife provides a bird’s-eye view of the landscape: an astonishing network of lakes and trees that extend uninterrupted in every direction as far as the eye can see.

The hard-packed gravel runway at the Lutsel K’e airport offered a soft landing for the visiting delegation, which was whisked to the village in the back of a pickup truck.

In early June, there is still ice on Great Slave Lake, and a light breeze brings its chill into the community, despite sunny skies that push the temperature toward 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Fishing boats line the shore, and four-wheel all-terrain vehicles are the transport mode of convenience for residents, speeding travel between the Lutsel K’e band office to the village Co-op store and surrounding homes.

Inside the Wildlife, Lands and Environment building, former Lutsel K’e chief Addie Jonasson explains the sacred importance of Thaidene Nene to the Dene people and emphasizes the need to protect it from being fragmented by mineral development.

© 2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

© 2014 The Pew Charitable TrustsAddie Jonasson, a former chief of the Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation, says the creation of Thaidene Nene National Park Reserve is a key element of the community’s plans to conserve ecologically and culturally important parts of their traditional land in Canada’s boreal forest region.

The surrounding area has deposits of uranium, diamonds, and precious metals, and it has drawn increased interest from mining companies in the past decade.

The Lutsel K’e First Nation recently negotiated an “impact benefit agreement” with developers of a major diamond mine elsewhere on their traditional lands. That deal would secure training, employment, and other financial benefits for the community if the project proceeds.

But Thaidene Nene is to be off limits.

“We are very outspoken when it comes to resource development, and also when it comes to protection of our traditional territory and homeland,” Jonasson says. “And that is because we want to make sure that our traditional territory is protected, that the land is protected, and that the water, the wildlife, animals, the birds are protected.”

Thaidene Nene’s protected area would include important ecological features, including a portion of representative northwestern boreal uplands. It also would cover traditional Lutsel K’e fishing and hunting grounds.

“Within our territory, Thaidene Nene is where we don’t want any development,” says Steven Nitah, another former Lutsel K’e chief and the band’s lead negotiator on the park’s creation. “We want to protect those lands, the water, the air, the animals, and our way of life, and our way of viewing the world.”

With Canada’s courts increasingly confirming First Nations’ rights and title to traditional territory, aboriginal peoples are assuming a central role in conservation planning in the boreal forest region.

Lutsel K’e’s hopes for Thaidene Nene provide insight into one First Nation’s vision.

The band is seeking to establish a $30 million trust fund to help develop ecotourism infrastructure and support education for young community members in key fields such as environmental monitoring and resource management. Dene stewardship traditions would be a foundation of the training.

The hope is the new park will generate a sustainable tourism economy that can provide long-term employment opportunities for Lutsel K’e, which would serve as the gateway to the Thaidene Nene reserve.

Lutsel K’e’s business plan envisions Thaidene Nene potentially attracting more than 1,000 visitors a year. That’s a tiny fraction of the number of tourists who flock to iconic, accessible Canadian wilderness areas such as Banff National Park, but it would be a boon for a small community eager for economic diversity.

A significant component of the plan, community leaders say, is the creation of a “Watchers of the Land” program, in which band members would be trained as stewards to protect the ecological and cultural integrity of sacred Dene sites within the park.

The mandate of these Dene “watchers” would include providing interpretative tours for visitors, and passing on cultural and scientific knowledge to other members of the community.

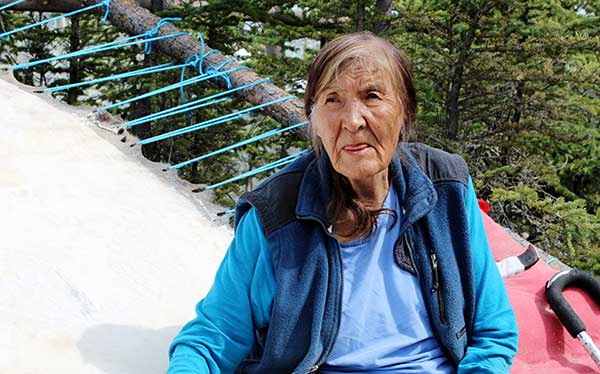

© 2014 The Pew Charitable Trusts

© 2014 The Pew Charitable TrustsMadeline Catholique, an elder in the Lutsel K'e Dene First Nation, takes a break from scraping a moose hide at a traditional tanning camp on the shores of Great Slave Lake.

That tradition of teaching was on display at the moose hide tanning camp, which was set up a short drive from the village itself. Younger members of the village—and some people from outside the community—actively participated in the tanning and learned the old ways from Dene elders.

The camp showcased the enormous pride the Lutsel K’e Dene have in their heritage, and their strong connection to the land and its natural beauty. Nitah expresses the sentiment when he greets the Boreal Leadership Council visitors.

“We wake up to this view every day,” Nitah says of the surrounding landscape. Because of that, “we are born conservationists. We are born environmentalists.”

Sheldon Alberts is a communications officer for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ International Boreal Conservation Campaign.