To Hades and Back: Here Be (No) Dragons

A super-giant amphipod recovered from 7,000 meters in the Kermadec Trench. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

By Ken Kostel

ABOARD THE R/V THOMAS G. THOMPSON—Everything is out of the water and on deck. The bio lab is quiet and the cold room is empty, save for the samples that have to remain at hadal temperatures for our transit to port. For the next 900 miles and four days, we steam north-northeast to Apia, Samoa, following the line of the Kermadec-Tonga Trench almost all the way.

It seems almost laughable that our tiny transects at the southern end of the Kermadec will do anything to advance knowledge of hadal ecosystems, but the simple fact that they already have, and will continue to do so, tells you how little we know about this dark corner of the globe.

Our samples represent the most comprehensive collection of hadal animals spanning from 4,000 meters to the bottom of the trench at 10,000 meters. We have quadrupled the number of snailfish collected—the deepest known fish in the ocean—on this one cruise alone. We have samples of rare and unknown animals collected by Nereus (our lost submersible) and brought up in the fish trap, including something that resembles a cross between an anemone and a sea cucumber that has stumped everyone on board. We also recovered evidence that pumice floating on the surface collects algae and animals and then sinks to the seafloor six miles below, providing yet another way for food and carbon to cycle through the ocean. The larger discoveries will have to wait, however, until we get everything back to labs around the world.

HADES chief scientist Tim Shank (left) and Aberdeen University biologist Alan Jamieson examine some of the specimens brought up by Nereus. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Perhaps our biggest discovery was not so much a revelation as a confirmation of something that we all suspected from the beginning—that the deep-sea trenches are far more varied and complex than previously believed. When we dropped the photo and video landers onto a part of the seafloor that looked fairly level after surveying with the ship’s multibeam sonar, we were twice surprised to see rugged terrain and, in one instance, a lush sponge garden. On several occasions, when Nereus traveled across flat, featureless sediment ponds, it came up against a sheer cliff face or a steep drop-off that did not appear on our maps.

The range of habitat we surveyed mirrored the phenomenal diversity that we encountered, from clusters of stalked anemones found only in deep trenches to lone amphipods curled up on rocks. Amazed as we were by these sights, we could always turn to our maps, trace out features that did register, and imagine what we might find if we could just move a few kilometers in any direction.

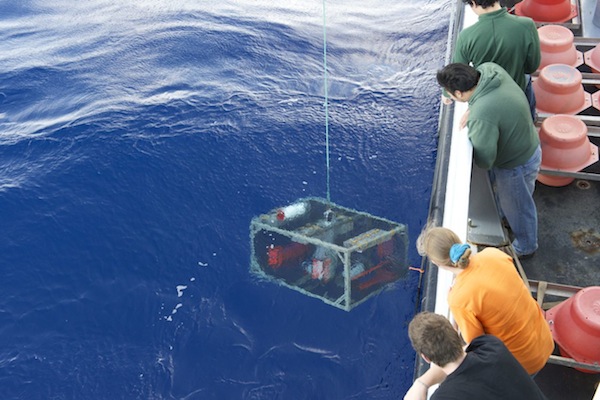

Members of the science party wait for the fish trap to return from a 7,000-meter deployment. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

The truth about the hadal zone is that it is not an alien planet here among us, it is simply another of Earth’s biomes – one with a range of ecosystems and some admittedly harsh conditions compared to our warm, low-pressure, oxygen-filled home. In the end, however, it is just one point on the continuum of places where life has been able to take hold and thrive on Earth.

Our tendency to characterize the depths as “mysterious” and “alien” doesn’t stem from the creatures that live there, but rather from our own ignorance. We once put dragons on the edge of maps, Nessie swims the remote lochs of Scotland, Sasquatch and the yeti roam the forests and hills beyond civilization. It’s only when we look closely that we find that the dragons are just the mind’s attempt to explain what we don’t know.

This is not to say that life in the trenches is prosaic or uninteresting. Quite the opposite. The simple fact that life has been able to spread in such complex forms to the deepest reaches of the ocean tells us something about its flexibility and adaptability. Every camera survey, every fish trap recovery, every humble sediment core has raised more questions than each could possibly answer and has underscored one much larger question that will probably never be completely answered. If life can stretch to the trenches in such diversity and abundance, where else could it be?

Aberdeen University graduate student Thomas Linley takes advantage of the light on deck to take photos of a snailfish that he will stitch together into a single, high-resolution 3-dimensional image. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Shane Hunt, an undergraduate student at Point Loma Nazarene University sorts amphipods that will be studied for their adaptations to life in the deepest part of the Kermadec Trench. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Our brief look into the Kermadec has shown us things and places that no one has ever seen before. It has also shown us that, indirectly, humans made their presence felt here, and probably in all of the trenches, long before we arrived. We found a soda can in one of the lander images; Nereus found a raincoat at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. One of the studies that will arise from samples collected on our cruise will be to examine amphipods taken from various depths for signs of PCBs and other human-made contaminants. Initial studies have indicated they are there, but confirmation would prove that, no matter how far down the hadal zone extends and no matter how different it is to our home on land, the depths are inextricably linked to the surface. What this means for the trenches, however, is a mystery because we lack any knowledge of what the hadal ecosystem looked like before humans came on the scene.

We can, however, begin to piece together a bigger picture of ocean trenches based on the information we have gathered and will continue to gather. That is one of the reasons the HADES program was formed—to extend our knowledge through time and to other trenches around the world and to banish the dragons once and for all to the depths of our imagination, where they belong.

This article was originally published by Scientific American.