A Starring Role for Pacific Forage Fish

By Erik Robinson

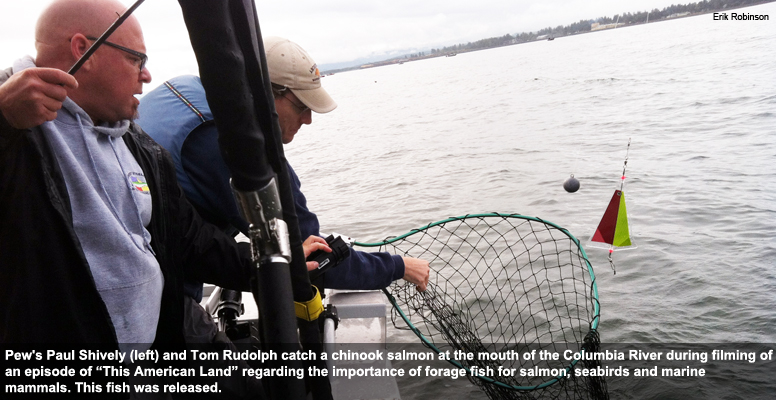

Cruising around the Columbia River estuary near dusk in late August, a film crew with the syndicated PBS program “This American Land” had a front-row seat to one of the most vibrant food webs on the planet. Pelican after pelican plunged into a buffet of anchovies teeming just below the water's surface as the camera captured it all from the deck of a federal research vessel.

Then a few dozen yards off the starboard side, a telltale sign of something bigger. Much bigger.

“That's a whale!” someone shouted.

The gray whale was close enough that we could easily glimpse its outline and spout, within sight of the Washington town of Ilwaco on the north bank of the Columbia. Veteran researchers say it's unusual but not unprecedented to spot a whale drawn into the river's mouth by a flood tide rich with anchovies. The whale's presence vividly illustrated the allure of small schooling species of prey fish—commonly known as forage fish — that feed on plankton, the microscopic plants and animals drifting near the surface, and then become food for a plethora of marine life higher in the food web.

This segment of “This American Land,” expected to air on many PBS stations early in 2014 focuses on the importance of forage fish as the critical but often overlooked link in healthy marine ecosystems along the Pacific coast.

Known as the California Current, the ocean environment off the West Coast is one of only a half-dozen large marine ecosystems in the world characterized by upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water. Prevailing winds cause nutrients to be pulled from ocean depths, stimulating the growth of plankton in the spring and summer. Forage fish such as sardines, anchovies, and smelt gorge on these blooms of life in vast schools known as bait balls.

Seabirds, sharks, whales, and highly migratory fish such as tuna travel thousands of miles across the Pacific to the relatively narrow North American continental shelf to feed on these oil-rich species. Forage fish thus link the plankton at the bottom of the food web to all the predators at the top, including the salmon that pour out of the sprawling Columbia River basin.

Despite their importance to ocean food webs, forage fish are caught extensively around the world. Here on the West Coast, commercial fishermen target sardines and anchovies using purse-seine nets. Other forage fish, such as saury and sand lance, aren't yet being targeted, but they are susceptible to new fisheries starting up with no catch limits or restrictions of any kind. Fortunately, the Pacific Fishery Management Council, the federal entity charged with managing ocean fish along the Pacific coast, agreed in September to prohibit new fishing on forage fish that aren't currently monitored or managed. A working group of state and federal officials will report back to the council in the spring of 2014 with options to make this prohibition legally binding in federal waters 3 to 200 miles offshore.

California's Fish and Game Commission adopted a similar precautionary policy for state waters in 2012, and in 1998 Washington put in place a forage fish management plan that makes conservation of forage species a priority because of their role in the ecosystem. Oregon remains the one place along the U.S. Pacific coast without a policy to protect forage fish within 3 miles of its coastline.

Worldwide, forage fish account for more than a third of the total catch of marine fish, with 90 percent reduced to fishmeal or oil for purposes such as feeding livestock and farmed fish. Yet the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force, a group of 13 eminent scientists from around the world, calculated in 2012 that forage fish are worth twice as much in the water as they are in the net. The reason: the commercial value of predators—including salmon, tuna, and cod—that eat the forage species. The task force recommended that no new fisheries be initiated on forage species when we have little information about their population health, their migration patterns, and the degree to which predators depend on them for food.

Populations of forage fish along the West Coast fluctuate widely, meaning an abundance one year can dwindle unexpectedly the next. That's problematic for fishermen targeting forage species, but it can be deadly for the marine wildlife that depend on them for sustenance. In the past decade alone, a shortage of forage fish has been linked to failed salmon runs, starved sea lion pups, and declines of seabird populations.

Pacific sardines are a case in point. Immortalized in John Steinbeck's classic novel “Cannery Row,” the West Coast sardine population collapsed almost completely in the 1950s after decades of severe overfishing. The population slowly rebuilt, gradually spreading northward to the point that in 1999 it could support a sardine fishery around the mouth of the Columbia River after decades of dormancy. In 2012, the Northwest accounted for almost 80 percent of total sardine landings along the entire West Coast. Most of this catch is exported for purposes such as bait for industrial longline fishing in Asia or feed for farmed fish.

Unfortunately, the overall sardine population is once again contracting. Coastwide, the catch of Pacific sardines has shrunk from 127,500 metric tons in 2007 to 51,300 metric tons so far this year. The catch limit for 2013 is just 57,500 metric tons.

At the same time, researchers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Fisheries Service continue to strengthen scientific understanding about the role of forage fish in the marine environment. In fact, the film crew from “This American Land” was on board a NOAA Fisheries research vessel in late August when the camera captured remarkable images of marine life nourished by the dense schools of anchovies within the mouth of the Columbia River. As each pelican emerged with a beak full of the small fish, a bevy of common murres, double-crested cormorants, and gulls swarmed in for their share.

Earlier in the day, the film crew had watched from the mouth of the river as an armada of fishing boats vied for fall chinook salmon fattened by a diet of forage fish during the two to three years they spent in the ocean.

The salmon don't eat much when they arrive in the river—they're on a single-minded journey upriver to spawn—but forage fish such as anchovies, sardines, herring, and whitebait smelt sustain plenty of other predators. Seabirds, harbor seals, and sea lions are easy to see, and fishermen routinely pull in myriad species of rockfish with half-swallowed forage fish still in their mouths. During its day on the water, the crew from “This American Land” witnessed many of these sights firsthand. Early next year, viewers will have their chance to see them, too.

Erik Robinson works to conserve West Coast forage fish for The Pew Charitable Trusts in Portland, OR.