New Kimberley Protected Areas Form One of the Largest Indigenous Conservation Zones in Australia

Four large new Indigenous Protected Areas have been established in the rugged and remote Kimberley region of Western Australia, creating a conservation corridor equivalent in size to the state of Indiana.

The Australian Government and the Indigenous people of northern Kimberley formally created the protected areas at a ceremony on the Dampier Peninsula this week. More than 400 Indigenous people gathered May 23 to celebrate the announcement on the stunning landscape at the sea's edge.

The declaration protects 85,110 square kilometres (32,861 square miles) of unspoiled coastline and tropical savannah. It represents the latest chapter in the story of successful Indigenous conservation in Australia.

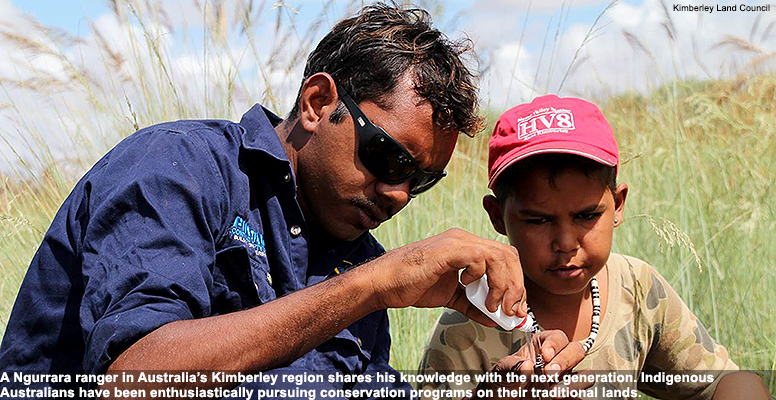

Indigenous Australians have been enthusiastically pursuing conservation programs on their traditional lands. There are now 58 Indigenous Protected Areas, or IPAs, across Australia, protecting more than 51 million hectares (126 million acres) of remote and biodiverse land.

The Pew Charitable Trusts has supported these efforts in three of the four new protected areas: the Bardi Jawi (354,867 hectares) near One Arm Point on the Dampier Peninsula, Dambimangari (2,639,405 hectares along the Buccaneer Archipelago), and Balanggarra (2,415,724 hectares across Wyndham).

The fourth protected area is the Wilinggin (2,761,000 hectares along Gibb River Road). Combined, the areas make up one of the largest Indigenous conservation zones in Australia and cover 20 percent of the Kimberley region, including other protected areas already in place.

These declarations supplement government announcements earlier this year that created the Great Kimberley Marine Park and the Wanjina National Park.

The Kimberley Land Council represents the land's Traditional Owners. Nolan Hunter, chief executive officer of the council, said creation of Indigenous Protected Areas or Aboriginal National Parks is the preferred land management model for Traditional Owners and Indigenous rangers.

“Indigenous Protected Areas are primarily managed and owned by Aboriginal people and allow us to look after our country our way,'' he said. “The Kimberley is home to unique biodiversity hot spots and significant Indigenous cultural heritage values. Our rangers are leading the world in conservation and land management and are pioneering new projects that use their wealth of traditional knowledge and culture to implement long-term management plans.”

In creating the protected areas, the Traditional Owners of the Kimberley have entered into an agreement with the federal government to manage their lands for conservation. This helps attract funding so that the Traditional Owners can make decisions about priorities for conserving and protecting the natural environment.

These programs have delivered significant cultural, social, environmental, and economic benefits for Indigenous people, who are often socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Indigenous rangers play a role similar to that of national park rangers in managing the IPAs. But as local Indigenous people, they bring unique skills to the task of managing their native lands, using a combination of traditional knowledge and Western science.

This model of conservation has emerged not just as a success story for Indigenous peoples, but also as a world-leading approach to conservation.

The Kimberley is home to unique biodiversity hot spots and significant Indigenous cultural heritage values. Our rangers are leading the world in conservation and land management and are pioneering new projects that use their wealth of traditional knowledge and culture to implement long-term management plans.Nolan Hunter, chief executive officer, Kimberley Land Council

“Indigenous ranger programs are successful because they build on an enduring cultural relationship of people to their land and sea,” said Barry Traill, who directs Pew's Outback Australia program. “The enduring success of these programs demonstrates that people want to be on their land and take care of it.”

Currently, 14 ranger groups employ more than 100 Aboriginal rangers and their elders across the Kimberley.

Phillip McCarthy, head ranger for Bardi Jawi, said the Kimberley Ranger Network and the Indigenous Protected Area program have generated change at a grass-roots level and strengthened communities.

“Kimberley rangers want to lead this global network of Indigenous land and sea managers and help drive it from the ground up,'' McCarthy said.

“The Bardi Jawi Rangers started from humble beginnings, but in the last seven years, we have grown to become a specialist team. We recently travelled to Abu Dhabi at the request of the United Arab Emirates Government to share our skills in satellite tagging and dugong research with the local rangers,” he added, referring to the large marine mammals that live in the region's waters.

“Sharing our knowledge and learning from other Indigenous groups is the way forward,'' he said. “Together, we can tackle environmental challenges on a global scale and set the benchmark for conservation standards.”

Traill said the protected areas are working for the land and for the Indigenous people.

“In often extremely challenging situations of social disadvantage and vast remote areas, Indigenous people of the Kimberley are actively expressing their living culture and strong desire to be living on and managing their land and sea country,” Traill said. “Indigenous Protected Areas not only act to safeguard the natural environment but deliver economic and social benefits for local Indigenous people through the creation of long-term jobs, training and education opportunities.”