Changing Course for America's Oldest Fishery

“The fish just aren't there.” This simple observation from Cape Cod fisheries manager Tom Dempsey to the Associated Press sums up the challenge of decreasing cod populations.

Recent scientific studies estimate that cod populations are at or near record lows. But this serious problem has not stopped the New England Fishery Management Council from proposing to end protection of their waters off the New England coast, a move that will make it even harder for cod—a fish that helped build the region's economy—to recover.

The fish just aren't there. - Tom Dempsey, Cape Cod fisheries manager

It is difficult to overstate the importance of cod to New England. America's oldest fishing ports grew and thrived because of once-abundant schools of the species. “The sacred cod”—a wooden carving—hangs in the Massachusetts statehouse. And, of course, there is the famous cape named for the fish.

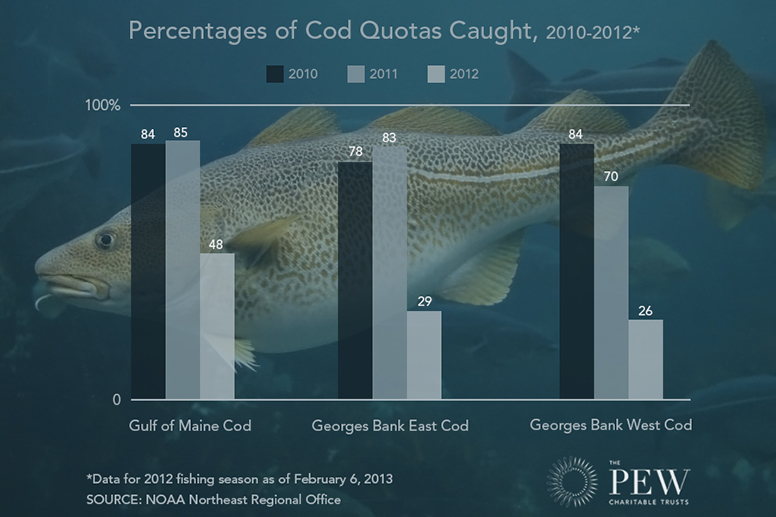

But Cape Cod fishermen have largely given up on their home's namesake. Cod averaged more than $3 per pound at auction for much of 2012—a very high price. But the catch from nearby Georges Bank has been so paltry that fishermen barely landed one-third of their allotted quota.

Why are cod and many other species of groundfish, or bottom dwellers, struggling to recover? Decades of heavy fishing depleted their numbers and damaged the ocean ecosystem. These fish now face additional challenges from climate change as New England waters hit record high temperatures in 2012.

At the last meeting of the council in late January, grim reality set in among officials. “We're just headed toward oblivion,” John Bullard, regional fisheries administrator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said in reference to the scarcity of cod. “We have to change course.”

Despite considerable pressure from the seafood industry and its allies in Congress to allow overfishing to continue, the council held firm and approved painful but necessary cuts in the catch limits. These new limits for cod and other important groundfish are supported by the best science, and they follow the proven path for rebuilding fish populations as laid out in the nation's primary fishery law.

While the catch limits are an important step in the right direction, other proposals approved by the council risk further harm to an already battered ocean ecosystem. For most of the past two decades, New England's groundfish benefited from a network of areas closed to most bottom trawling and dragging. Created after fish populations crashed in the 1990s, these areas cover more than 8,000 square miles, sheltering spawning and juvenile fish, and allowing seabed habitats to recover from decades of damage. These protections played an important role in the recovery of some species, including scallops. Scallops now make New Bedford, Massachusetts the nation's richest fishing port.

Yet, in a move advocated by the owners of large vessels in the New England fleet, the council passed a measure that will end protection for more than half these areas. Roughly 5,000 square miles—the size of Connecticut—could be open to bottom trawling.

Author and noted marine biologist Callum Roberts recently wrote that opening the protected zones will be disastrous because a “linchpin of fishery recovery” could be “wiped out in less than a season's fishing.”

The council's proposal to open these protected areas to bottom fishing now rests with officials at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Their decision will test their commitment to truly set a new course for one of America's most storied fish—and one of its most historic fishing grounds.

This article originally ran at newswatch.nationalgeographic.com.