Dispatches from the Marshall Islands

- October 25, 2012 - Song of the Sea

- September 24, 2012 - Protecting Sharks That Protect Islanders

Song of the Sea

By Angelo Villagomez

October 25, 2012

Isn't it funny how fate can intervene sometimes?

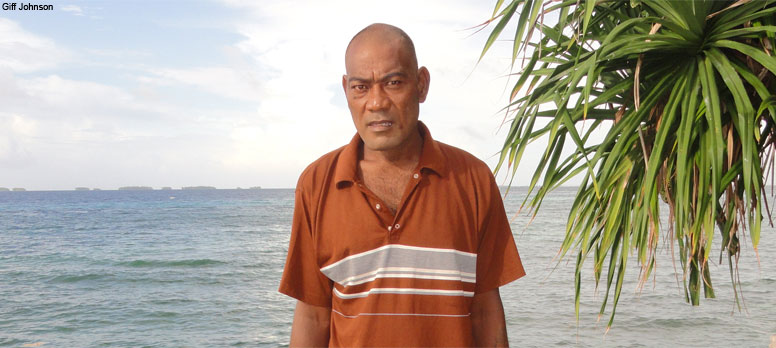

Niten Anni, a Marshalese native sings about his culture and its ties to the ocean.

The day I met Niten Anni, I was sitting outside having lunch with filmmaker Shawn Heinrichs in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands. We were visiting the Pacific island country to participate in a training session on marine enforcement and to film a movie about sharks and the Marshall Islands, home of the world's largest shark sanctuary.

While at the restaurant, Shawn and I were making plans to get to the Marshalls island of Kwajalein to see for ourselves whether stories of waters teeming with sharks were true. As we talked, a young man walked by, strumming a ukulele. We learned that he was a Marshallese musician, Niten Anni. I asked him if he would sing a few songs for our video and, lucky for us, he agreed.

Niten sang several beautiful songs in Marshallese about the surrounding ocean and his Pacific culture. He sang about his home island of Mejit, a distant spot with a population of 300. He sang of the people and of life on the island, and while Shawn and I listened, we were stunned that we had simply stumbled upon him by chance.

Sharks have been a part of Marshall Islands folklore and culture for centuries, and people living among the atolls understand that these animals play an important role in ocean and island health. Niten told us that he's proud that his country has the world's largest shark sanctuary. He's proud that it is protecting sharks.

My hope is that this sentiment is shared by millions of others around the world and that someday the entire Pacific may sing a similar tune.

Sharks have been a part of Marshall Islands folklore and culture for centuries, and people living among the atolls understand that these animals play an important role in ocean and island health.

“Niten sang several beautiful songs in Marshallese about the surrounding ocean and his Pacific culture. He sang of the people and of life on the island, and while Shawn and I listened, we were stunned that we had simply stumbled upon him by chance.” – Angelo Villagomez, senior associate, global shark conservation

Protecting Sharks That Protect Islanders

By Angelo Villagomez

Sept. 24, 2012

On Saturday, Sept. 15, a tuna boat pulled into the harbor at Majuro, Republic of the Marshall Islands, carrying a passenger with a strange tale to tell. Toaki Teitoi, 41, a police officer from Kiribati, had been lost at sea for nearly four months. He said a shark saved his life by guiding his tiny boat to the fishing vessel that rescued him.

Toaki Teitoi was rescued by a tuna fishing vessel after spending four months adrift at sea in his 15-foot dinghy.

For centuries, Pacific Islanders have told similar stories of sharks rescuing fishermen. These stories stretch across Oceania, from my home in the Mariana Islands to Hawaii, south to Fiji and to all points in between. The sharks and the fishermen have a pact: As long as fishermen respect them, the sharks will protect the fishermen.

Gray reef sharks, which are protected from commercial fishing in the Marshall Islands, are common visitors to the 34-island nation.

It is not surprising, then, that Mr. Teitoi was rescued by a shark in the Marshall Islands, because the government has made its respect for sharks official. In 2011, the Pew Environment Group worked with the Marshall Islands to implement a policy banning commercial fishing of sharks and the possession of fishing gear used to target them. With fines as high as $200,000, the Marshall Islands has the world's strongest protections for sharks. And with an exclusive economic zone of 1.9 million square kilometers (734,000 square miles), it also has the biggest shark sanctuary in the world.

Pew's Angelo Villagomez, giving a presentation on the global conservation status of sharks at the enforcement workshop.

On the day Mr. Teitoi was rescued, I was participating in a workshop in Majuro, the Marshall Islands capital, to help government agencies enforce the country's marine conservation laws. The Pew Environment Group organized the training, along with our partners the Micronesia Conservation Trust, the Marshall Islands Conservation Society, and the Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority. The goal was to encourage the national and local police and the resource agencies to collaborate on marine protections and to build capacity within each agency.

Capt. Joey Terlaje, an enforcement trainer from Guam, shows participants how to correctly subdue a suspect.

Illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing is a problem all around the world as it undermines management efforts to control overfishing and poses a major threat to the health of fish stocks and other ocean life. Presently, the countries with some of the strongest protections for sharks have the lowest capacity to enforce their laws, however, they are doing what they can to protect their marine resources. Over the past year, we have seen a number of high profile seizures of illegal fins in Palau and Honduras. Additionally, the Marshall Islands have successfully prosecuted five violations resulting in fines of $235,000 in the last several months.

During Villagomez's visit to the Marshalls, he found beautiful coral reefs patrolled by sharks. Although the numbers have declined from historical levels, the new protections will help populations rebound. This resource will attract divers from around the world.

Enforcement of these important sanctuary protections comes at a critical time. Scientists have estimated that reef shark populations around populated islands in the Pacific have plummeted 90 to 97 percent from historical levels[i] and that up to 73 million sharks are killed each year for their fins.[ii] Around the world, 150 species of sharks are threatened or near threatened with extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.

Before his encounter with the shark Mr. Teitoi reckoned he spent 104 days at sea curled up in the bow of his boat under a small covered area that gave him protection from the sun. On the 105th day, he heard a scratching on the hull, and when he peeked out to see what it was, he saw a six-foot shark circling him. Suddenly the shark swam off. “He was guiding me to a fishing boat,” Mr. Teitoi said. “I looked up, and there was the stern of a ship, and I could see crew with binoculars looking at me.”

The reciprocal pact between shark and man was once again reaffirmed.