Overfishing 101: New England's First Year of Fishing Under Sectors

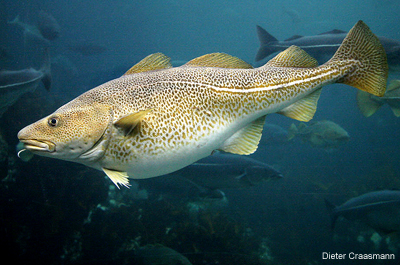

Since 1784, a five-foot wooden carving of a cod has hung from the ceiling of the Massachusetts State House—a symbolic reminder of the important place this fish holds in the hearts of New Englanders. Cod, along with other groundfish such as haddock and flounder, has supported coastal towns and economies throughout the Northeast for hundreds of years. Much has changed since the early days—boats have gotten larger and faster, satellite navigation has replaced compasses and paper maps, and fish are now refrigerated instead of salted and dried.

But advanced equipment and techniques sometimes carry unintended consequences. Beginning in the 1980s, these improvements, along with federal government incentives that allowed fishing fleets to expand to unsustainable levels, resulted in the well-documented crash of New England's cod populations.

Fishery managers attempted to restore this once-abundant species by limiting the number of days that boats could spend on the water and how many fish they could bring to port each day. But this proved to be bad for the industry and for the fish.

Because fishermen were running against the clock, they were forced to fish as hard as they could during the few days they were allowed on the water, sometimes putting their safety at risk in bad weather. Additionally, because of daily limits on cod and other species, fishermen were often required to throw thousands of pounds of marketable catch overboard if they exceeded the limits. With fish populations steadily declining and people losing their businesses, New England desperately needed a new approach.

In response, the New England Fishery Management Council, which includes fishermen and other stakeholders from every state in the region, developed an innovative plan to reform the way these fish are caught. Following an exhaustive multiyear public process, the council set enforceable catch limits based on science and created a system of cooperative fishing groups called sectors.

In this system, which began in May 2010, fishermen voluntarily join a cooperative, usually selecting a group based on fishing gear type or port. The National Marine Fisheries Service assigns fishermen yearly quotas depending on their historical landings, which they then bring into the group, where the quotas are managed as a whole.

Sector members create a business plan that makes clear how the allotment will be divided and how, when and where they will fish. Onboard observers, dockside monitors and electronic reporting are used to track the landings of each boat, and members can buy or lease more fish from a cooperative or buy it from other fishermen if they exceed their initial allotment.

As is common when new replaces old, some feared this system would make the situation worse. However, preliminary data from the first year of fishing under the sector system show that these concerns were unfounded. Science-based catch limits were not exceeded for any species, wasteful discards of marketable fish were reduced, total catch was almost identical to the year before and revenue rose as the price fishermen were paid increased. Fishermen also created innovative marketing techniques and developed more selective gear to help them avoid catching non-targeted species.

The National Marine Fisheries Service is preparing a complete report on how this new system performed in its first year. The analysis should be released in early fall, so stay tuned for more details.

Going forward, there are several ways to make the sector system even more successful and continue to provide opportunities for New England's traditional small-scale fishermen to prosper. Permit banks, which sell or lease quotas at below-market rates, would help ensure that small-boat fishing communities could stay in business. Current regulations allow a maximum of 10 percent of a year's unused allotment to be used in the next fishing year. Increasing the allowed rollovers, if justified by science, would provide more fish for fishermen.

Many things have changed both on land and in the water since that wooden cod was first hung in the Massachusetts Colonial legislature nearly 230 years ago. But the fishing industry is still at the heart of many New England communities, and the continued health of the fish populations off their shores remains the key to their future success.

As fishermen and managers adjust to the new sector system, they must continue to work with the best available science, sustainable fishing limits and new, more environmentally friendly gear types. We all want to work to ensure that the latest change is for the better and will help provide healthy fish populations, a successful industry and prospering coastal communities for generations to come.