The Bottom Line: Don't Remove Protection When Cod Need It Most

New England is famous for cod fishing. But the industry is ailing – and the cure being proposed might be worse than the disease. Three months ago, the U.S. Commerce Department declared a “commercial fisheries disaster” off the coast of New England because populations of groundfish – cod, haddock, and flounder, among others – were still struggling to recover. Substantial cuts in the allowable catch for the upcoming season are needed to prevent overfishing. Unfortunately, a proposal by regional fisheries managers to reopen areas where groundfish are currently protected is a big step in the wrong direction.

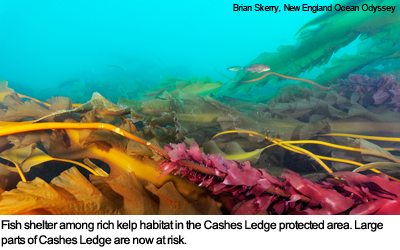

After many fish populations collapsed in the early 1990s, large sections of New England waters were closed to bottom trawling. This wise move protected seafloor habitat and provided safe places for spawning and for young fish to survive to maturity. Now the New England Fishery Management Council wants to open more than half of these sheltered zones to commercial fishing. This is an area roughly the size of Connecticut. The proposal would allow bottom trawling and other destructive fishing methods that damage seafloor habitat. Opening these areas is a significant ecological risk – with no guarantee of long-term economic benefit for our coastal communities.

Populations of cod and other important species are still recovering from the lingering effects of decades of overfishing, and they face additional challenges as warmer water disrupts distribution patterns that evolved over the ages. Allowing new habitat destruction could deplete New England's fish population to a level where it is no longer commercially viable. This is exactly what happened in Canada's Atlantic waters in the 1990s.

The council's proposal is shortsighted and skirts requirements for full public participation and study of the environmental impact. Major changes to the management of public resources demand transparency and accountability.-Lee Crockett, director, U.S. Ocean Conservation

Marine scientists are not alone in their opposition to the council's proposal. Many small-boat fishermen and recreational anglers also oppose the change. They believe – with good reason – that the operators of larger boats with bottom dragging gear are most likely to benefit, while some smaller vessels may be displaced. The captains of smaller vessels are the ones bearing the brunt of the fishing industry's economic crisis. There is strong evidence that the protected areas support long-term recovery of New England's groundfish populations. Peer-reviewed science demonstrates that fish move from closed areas into surrounding waters. Many vessel operators take advantage of this pattern of movement by operating around the edges of the closed areas.

One study found that 25 percent of all New England fishing trips targeting groundfish occurred within three miles of a closed area. Average revenue for those trips was twice as high as elsewhere. Studies also show that some fish are larger and more abundant inside the closed areas. This gives cod and other species protected from trawling an advantage: larger and older fish can reproduce more easily and help rebuild depleted populations. That means closed areas are an investment that pays dividends. Exploiting these areas is akin to spending the principal rather than the interest. Before long your funds are gone.

The council's proposal is shortsighted and skirts requirements for full public participation and study of the environmental impact. Major changes to the management of public resources – and that is exactly what the council is proposing – demand transparency and accountability. I am confident that once people are aware of what's at stake they will recognize what many scientists and fishermen already know: these protected areas work. Removing them now could undermine the long term recovery of cod and other species that so many depend on.

This article originally ran at newswatch.nationalgeographic.com.