Vibrio Infections in the U.S. Increased Significantly in Recent Years

More on Vibrio

Vibrio infections can cause diarrhea, sepsis, wound infections (acquired through contact with contaminated water or handling of contaminated food, not by consumption), and other extra-intestinal infections.

V. parahaemolyticus is the most common vibrio species found in the United States and is responsible for about half of the infections.

V. vulnificus is the deadliest one. More than 80 percent of the patients require hospitalization, and more than 30 percent die.

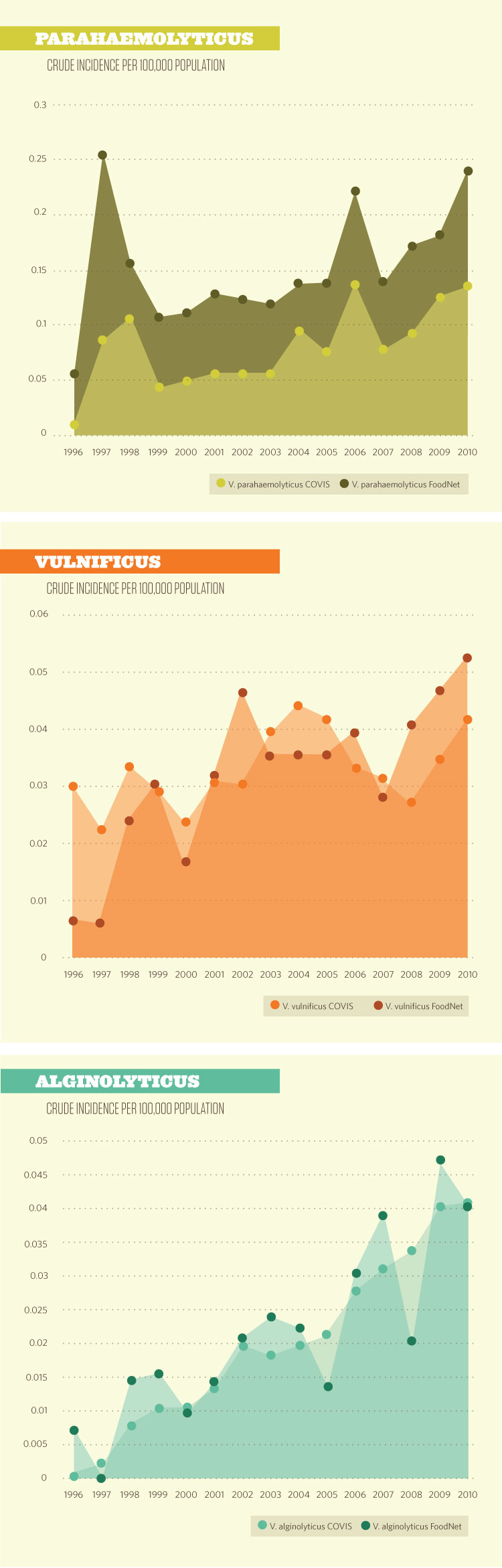

During a 15-year span beginning in the mid-1990s, infections in the United States from the pathogen vibrio have increased threefold, according to data published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC.1

Vibrios are bacteria that occur naturally in saltwater. Roughly a dozen species are known to cause disease in humans; illness usually occurs as a result of exposure to seawater or consumption of raw or undercooked seafood. The species include Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. vulnificus. CDC keeps records of vibrio infections though the Cholera and Other Vibrio Illness Surveillance System, or COVIS, and the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, or FoodNet.

According to CDC data published in June 2012 in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, cases of vibrio infection nearly tripled from 1996 to 2010. Of all the illnesses, 68 percent were reported in males; the largest percentage of cases were in men 40 to 49 years old. The infection rate was higher in coastal regions and peaked in the summer: COVIS pegs the rate at 40 percent, and FoodNet has it at 47 percent in July and August.

Data released by CDC in April 2013 reflect a continuing but less dramatic increase in vibrio infections. The information shows that the estimated incidence of vibrio infection was higher in 2012, compared with 2006 to 2008 (a 43 percent increase).2

Although COVIS and FoodNet capture some of these infections, vibrio illnesses are severely underdiagnosed: CDC states that for every confirmed case of an infection, 128 cases have not been diagnosed. CDC estimates that vibrio causes 80,000 illnesses, 500 hospitalizations, and 100 deaths in the United States annually. About 65 percent of those are estimated to be foodborne.3

Because the pathogen thrives in warmer temperatures, the number of infections rises during summer months. The steady warming of the oceans and coastal waters likely contributes to vibrio's growth and persistence, and the increasing number of infections each year.

Education efforts on the dangers of eating raw and undercooked seafood have not been sufficient by themselves, in CDC's opinion. However, there are post-harvest steps producers and suppliers of seafood can take to reduce the risk of vibrio contamination, including treating food with freezing and heating processes and washing with hydrostatic pressure.

In California, oysters harvested since 2003 from the Gulf of Mexico in warmer months are required to receive post-harvest treatment to reduce the level of V. vulnificus to nondetectable levels.4 This action appears to have significantly reduced V. vulnificus illnesses in the state.

Is it Safe to Eat Raw Oysters in Months With the Letter 'R'?

A common belief is that it is safe to eat raw oysters in months with the letter "R;" however, the Food and Drug Administration says that is a myth. While the presence of vibrio bacteria may be higher in warmer months, about 40 percent of cases occur during colder months, from September through April, according to CDC.

Read more about the myths and how to prevent infections at foodsafety.gov/poisoning/causes/bacteriaviruses/vibrio_infections/index.html.

Endnotes

- Source unless otherwise indicated: Anna Newton, Magdalena Kendall, Duc J. Vugia, Olga L. Henao, and Barbara E. Mahon, “Increasing Rates of Vibriosis in the United States, 1996-2010: Review of Surveillance Data From 2 Systems.” Clinical Infectious Diseases (June 2012): 54 (Suppl 5). cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/54/suppl_5/NP.1.full.pdf+html?sid=45e47910-ee4d-4f41-9100-6f1870c1c04f.

- Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food — Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 1996-2012. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 62(15) (April 19, 2013): 283-287. cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6215a2.htm.

- Newton, et al. “Increasing Rates of Vibriosis in the United States.”

- Defined as less than the most probable number per gram (MPN/g).