West Puerto Rico Fishers Call for More Participation in Management and Enhanced Enforcement

Interviewees also say pollution and changing climate are hurting Caribbean fisheries

A fishing boat approaches a dock at Mayaguez, on Puerto Rico’s west coast, at sunset.

Dr. Federico Cintrón-MoscosoWestern Puerto Rico fishers are worried about the state of their marine ecosystem and want to play more of a role in fisheries management, according to interviews conducted by a researcher and University of Puerto Rico professor.

Who’s Fishing in Puerto Rico?

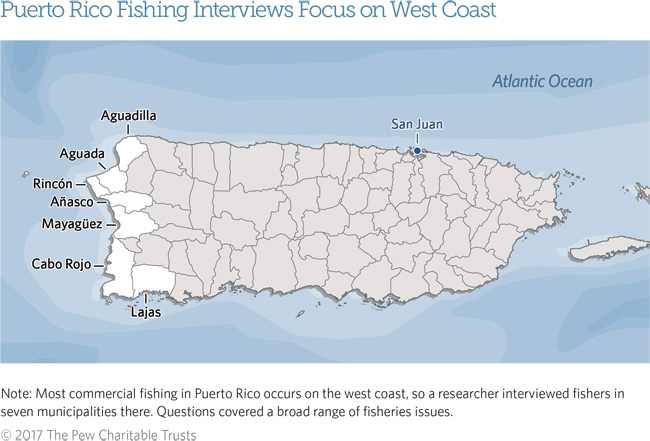

Most fishing in the U.S. Caribbean takes place on Puerto Rico’s west coast

- 1,500-2,000 active commercial fishers

- 120,000-170,000 estimated recreational fishers

(Island-wide data valid as of 2016)

Source: Dr. Federico Cintrón-Moscoso

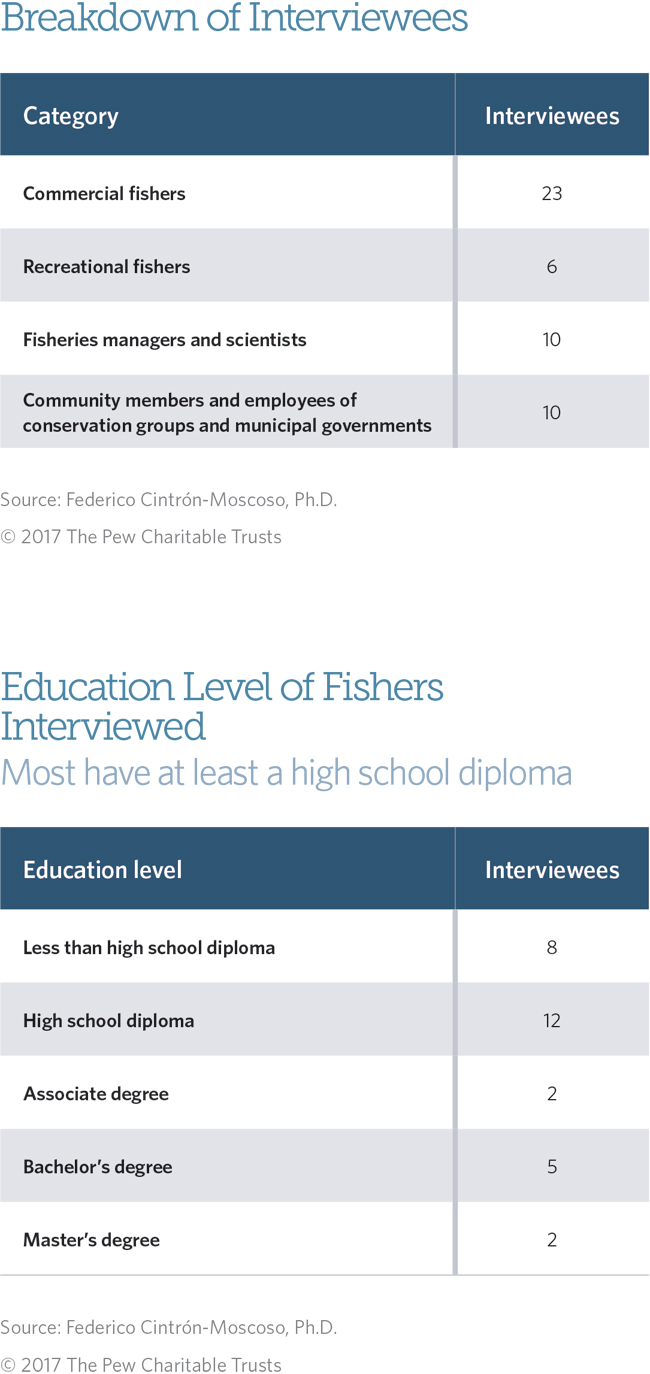

Federico Cintrón-Moscoso, Ph.D., a professor of ethnographic research at the school’s Río Piedras campus, questioned 49 fishers, government workers, environmental organization staff members, and others, and found widespread concern for the health of fish species and agreement that better coordination is needed between fisheries managers and those who work on the water.

The interviews, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, are part of an effort to better understand the opinions of fishers and fisheries managers, which in turn can help facilitate plans and rules to keep people fishing while also protecting the region’s valuable marine resources.

Cintrón-Moscoso conducted the interviews from May to September 2016 in western Puerto Rico. Here’s a summary of the results and background on the project:

Findings

The following findings represent the opinions and perceptions of only the stakeholders interviewed and are not representative of all fishers in Puerto Rico.

State of marine resources

- Almost all fishers interviewed agreed that land-based pollution, climate change, and overfishing have caused declines in the number of fish they’re catching and seeing. The interviewees also blamed the drops on an increasing number of unlicensed fishers and those who don’t follow the rules, such as seasonal closures.

- Most commercial fishers see value in seasonal closures, in which fishing for a specific species is prohibited during certain months, usually when the fish are spawning.

Environmental concerns

Fishers see fewer fish and believe they are moving to deeper waters due to climate change and pollution, which are damaging the ecosystem closer to shore. Fishers cited three major environmental concerns:

- Changing winds.

- Rising water temperature.

- Pollution, including trash, oils, and river sediments that are carried offshore by currents.

Management concerns

- The commercial fishers interviewed perceive management practices as unjust, believing that enforcement is arbitrary and regulations are lopsided against them. They have a general distrust of research and scientific data.

- Most fishers believe communication could be improved between them and the Caribbean Fishery Management Council, which oversees fishing in U.S. waters in the region. They would like the council to translate complex science and policies into simple terms and regularly engage the fishing community in meaningful conversations about management.

- Fishers are confused by sometimes conflicting goals, communications, and rules put out by state and federal regulators.

Fisheries scientists and managers agree that social and ecological data on Caribbean fisheries are limited. This lack of information can contribute to controversy and uncertainty when drafting local policies or implementing federal regulations.

Impacts of the fiscal crisis

Puerto Rico has been in a financial recession since 2006, and in 2016 ran out of money to pay its debts. This crisis is having widespread impacts across the island because the government lacks the funds to provide needed services to the community. The fishers interviewed for this project want better enforcement of regulations and fishing closures but believe the island’s fiscal crisis is hampering efforts to achieve that.

- The Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), the Puerto Rican government agency charged with environmental regulation and conservation, has only four fisheries officials to patrol the entire archipelago. (Puerto Rico also includes around 140 smaller islands, islets, and keys.)

- A government hiring freeze forced DNER to take on monthly contractors for numerous projects, including fisheries work. High turnover has meant recruiting and retraining contractors, which has been difficult.

Hopes for improvement

- A majority of those questioned see themselves as responsible for protecting marine resources. They want improved and strengthened relationships between policymakers and fishers, and they want to be an integral part of the decision-making process.

- Respondents also want improved educational efforts that go beyond informing the public about management actions. Rather, educational programs should create a new awareness that leads to change by providing hands-on training to help citizens develop and use pro-environment skills and practices.

- Commercial fishers want the government to educate people about fisheries law and ensure that laws are enforced. They want law enforcement personnel to be objective and effective in their work while using improved methods for catching wrongdoers. They also want the government to improve services and incentives for fishers and to treat them as partners.

- Most commercial fishers interviewed say they are willing to participate in policymaking if government representatives approach them with respect and a “listening” attitude.

Holly Binns directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ efforts to protect ocean life in the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. South Atlantic Ocean, and the U.S. Caribbean.