Data Sharing Helps Reduce Number of Homeless Veterans

Virginia’s information analysis assists in determining needs, managing resources

This is the third in a series of briefs on how states are using data for decision-making.

Overview

As veterans transition to civilian life, often after serving overseas in conflicts and wars, many confront a new battle: homelessness. During the 2007-09 Great Recession and the slow recovery that followed, a disturbing spike in the number of homeless veterans emerged as a national crisis. Although veterans represented 10 percent of the adult population in 2010, they comprised 16 percent of homeless adults, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Through collaboration and focused efforts, policymakers have made significant progress toward resolving the crisis on a national level. Virginia is leading the way, and in 2015 became the first state to “functionally” end veteran homelessness, meaning the state had housing available for those who would accept it and ensured that homeless experiences were rare, brief, and nonrecurring.

Achieving this milestone was not easy. Although federal money for meeting veterans’ needs had increased, Virginia and other states struggled to target available resources in the most effective way. In addition, the involvement of multiple community agencies made it a challenge to make quick and equitable decisions. In some parts of the state, the wait for housing was three times longer than in others, and decisions on who was eligible for supportive housing—the most expensive services—were sometimes inconsistent.

Officials responsible for homelessness and veterans services in Virginia recognized that linking and analyzing their programs’ data would allow them to better understand veterans’ needs, monitor trends, evaluate programs, and determine which approaches worked best. Furthermore, they found that individual-specific data would enable organizations to deliver the most appropriate housing resources to the veterans in greatest need. A wide variety of service organizations, as well as city, county, and federal agencies, worked together to share and coordinate their use of data, bringing the state’s rate of veteran homelessness to the lowest in the nation.

Virginia is leading the way, and in 2015 became the first state to ‘functionally’ end veteran homelessness, meaning the state had housing available for those who would accept it and ensured that homeless experiences were rare, brief, and nonrecurring.

Background

In 2010, Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell (R) established the Governor’s Coordinating Council on Homelessness, which convened Cabinet-level departments and member agencies to create and implement a plan to effectively address the needs of individuals and families experiencing homelessness.

The council’s focus was on reducing homelessness in the state overall, and from the outset it emphasized shifting to a Housing First model—which prioritizes providing permanent housing as quickly as possible— and using data more effectively to help support people who were experiencing homelessness. Better use of data became one of the council’s five strategic objectives and included increased attention on statewide data collection and coordination in order to track outcomes and demonstrate effectiveness.1

After Terry McAuliffe (D) became governor in 2014, he built on Gov. McDonnell’s efforts by launching an initiative focused on ending veteran homelessness and creating a subcommittee of the council to focus on this work. “The establishment of the Governor’s Coordinating Council and developing a strategic plan to reduce homelessness statewide provided the foundation to get the veterans initiative launched,” said Pamela Kestner, deputy secretary of the Department of Health and Human Resources and homeless outcomes coordinator.2

In June 2014, first lady Michelle Obama announced the creation of the Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness by the end of 2015. The Mayors Challenge was a collaboration by the White House initiative Joining Forces, the Interagency Council on Homelessness, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the VA, and was promoted by the National League of Cities through its Homeless Veteran Leadership Network. Multiple mayors joined the challenge, and Gov. McAuliffe became one of four governors to sign on that summer; the others represented Connecticut, Minnesota, and Colorado.3

Moving forward

To end veteran homelessness, Virginia officials had to ensure that “the right resources were distributed to the right individuals at the right time,” said Matthew Leslie, director of housing development for the state Department of Veterans Services.4

While some homeless veterans might need a modest amount of help after a job loss or eviction, others with drug or alcohol problems or a mental illness could require more expensive supportive housing that provides services along with shelter.

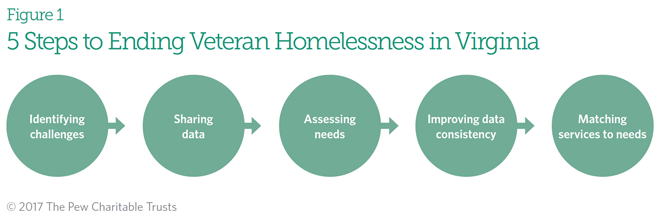

Virginia officials recognized that existing data could be leveraged to direct services in the most effective and efficient way possible. In practice, however, a number of challenges needed to be resolved before the state’s data could be applied to problem-solving.

• Identifying challenges. Concerns about privacy prevented data sharing between the VA medical centers, managed by the Veterans Health Administration, and Virginia’s 16 Continuums of Care (CoCs): planning bodies approved by HUD to coordinate the full range of homelessness services in a geographic area.

Compounding the issue, each CoC was free to choose and maintain its own data system. The different software systems made sharing the data difficult.5

The shortcomings in data sharing meant that both the CoCs and the smaller service organizations they work with (shelters, food pantries, housing agencies, mental health providers, and other outreach agencies) had limited information to work with. They could prioritize services based on data for their own clients, but community and state leaders could not get a full picture of the size or scope of veteran homelessness issues and therefore could not prioritize services on a community or statewide level.6

Because veterans tend to be a mobile population, there was also a concern that individuals might receive similar help from different organizations, leading to potentially wasteful duplication.

• Sharing data. The first step in improving data sharing was addressing privacy concerns. Two key factors helped to accomplish this.

First, support from the governor and Cabinet officials encouraged cooperation among stakeholders. “Leadership was an important piece of data sharing,” said Leslie. “You can want to share data, but if you don’t have the buy-in from leadership across multiple agencies, you won’t be able to motivate the boots on the ground.”

The second factor was the collegial relationships that had been forged among council members, who represented various secretariats and levels of government but developed trust in one another and worked to achieve common goals.

That trust helped lead to a breakthrough in fall 2014, when the VA agreed to share a veteran’s medical center information with regional CoCs and smaller service agencies if the person consented.

• Assessing needs. Once a veteran’s release of information was received, data could be organized and then supplemented by information gathered through a common assessment tool. Outreach and social workers gathered information on each veteran’s previous housing status, history of homelessness, visits to the emergency room, and police encounters, as well as information about relationships and mental health history. These records were scored so that each person’s need could be compared, creating a measure of vulnerability that became a part of the data set and could be used to prioritize the kinds of services being offered. “They identified, by name, every veteran they could find, and they assessed that veteran’s needs and identified what resources fit that veteran,” said Kestner.

The assessment tool gave the state a common set of criteria to be used by service organizations, VA medical centers, shelters, rapid rehousing providers, and permanent providers of supportive housing.

• Improving data consistency. The CoCs also became more adept at sharing data with one another. To some extent, coordination began to occur naturally in the years following the recession, as regional organizations gravitated toward software systems produced by a handful of dominant providers. Homeward, the planning and coordinating agency for homeless services in the Richmond area, offered to manage data for several smaller peers, further reducing the number of systems.7 Increased requirements from the federal and state governments to deliver consistent performance measures on a system level, rather than at the program level, also contributed to greater consistency in data definitions.

• Matching services to needs. On a regular basis, staff members from service agencies, the CoCs, and VA medical centers met to review the needs assessment scores in each region, one veteran at a time. These case conferences allowed the data to be translated into discussions of a person’s needs, with decisions made at a regional level instead of by a single provider. This meant that veteran needs could be compared, which helped to ensure that the more comprehensive and costly supportive services were delivered to the people who needed them most.

This led to an interesting discovery: Not all veterans being served by CoCs were identifying themselves as veterans. Managers found that some didn’t think of themselves as veterans, because even though they had been discharged or released from the military under conditions other than dishonorable, they had not served long enough to receive retirement benefits. If they didn’t identify themselves as veterans, they weren’t accessing VA vouchers for permanent supportive housing, which include counseling and other services to individuals with mental health or substance abuse issues or physical disabilities.8 To compile a more accurate list of veterans, caseworkers began asking clients if they had ever served in the armed forces rather than if they were veterans.

As Virginia worked aggressively to meet the Mayors Challenge goal, service decisions were focused on needs instead of on waiting lists for specific programs. This way, people began receiving services based on their unique needs and the kinds of services that could help them, rather than where they fell on a waiting list. An extensive political and managerial push to meet the Mayors Challenge also added a sense of urgency.9

Key strategies

1. Breaking down the silos. The cooperative effort of the Governor’s Coordinating Council on Homelessness— bringing together representatives from Cabinet departments, all levels of government and smaller agencies—built the trust needed to facilitate data sharing. In addition, the veteran-focused subcommittee of the council, made up of people from eight agencies, began meeting regularly. These agencies had connections to veterans but normally would not collaborate with one another. Through these meetings, program managers and department directors got to know each other, which helped to solve problems as they cropped up. For example, not all veterans have addresses to document that they are Virginia residents. Through the council, the Department of Veterans Services partnered with the Department of Motor Vehicles to allow homeless system data to serve as proof of residency.10

2. Identifying what works and what doesn’t. Virginia has become increasingly adept at using data to identify effective strategies and processes. Although its goal was to provide veterans with supportive housing within 90 days, the data showed it took as long as 250 days in some communities. Data analysis helped pinpoint the causes, such as requirements for unnecessary documentation, and helped local managers streamline these processes.11

3. Communicating success. Virginia has also drawn from HUD’s annual Point-in-Time count of homelessness12 to tout the success of efforts to reduce veteran homelessness. That, in turn, helped attract external funders, which supplemented federal, state, and local dollars with grants. Donors included several of the state’s utility companies—including Dominion Virginia Power, which pledged $2.5 million over five years for electricity assistance for newly housed veterans.13

4. Capitalizing on experience and connections. Human capital has played a key role in Virginia’s successful use of data to address veteran homelessness. When Leslie became associate director of housing development in the state Department of Veterans Services in 2013, he knew that plentiful homelessness data was available from housing agencies and that there had to be a way to connect disparate data systems.

Conclusion

Between October 2014 and December 2016, Virginia housed 2,737 veterans. But finding housing placements is just one part of a strategy to end veteran homelessness. Analyzing the data has helped Virginia recognize that veterans become homeless for a number of reasons and that connecting people with housing and then addressing individual needs, such as mental health treatment or employment, prevent long-term problems that become more intractable. There is also an increasing awareness within communities that data serves two distinct purposes: Aggregate data provides information about programs and how to improve them, while client-level data helps address needs on a personal level and improves the allocation of scarce resources.

Client-level data has helped to clarify that some people need very few additional resources. Those who are more vulnerable need support to find and navigate available services.

This work of linking and analyzing data has proven to be an ongoing effort. While data systems are far better coordinated than they were, data continues to be housed at local and regional levels. The Governor’s Coordinating Council on Homelessness seeks a statewide centralized information system on homelessness to help facilitate its efforts.

Although the state announced its success in meeting the Mayors Challenge and effectively ending veteran homelessness, more work remains to be done. “Functionally ending veteran homelessness was a milestone, but the reality is that we’re always ending veteran homelessness, as new individuals continue to fall into housing crises,” said Leslie. To meet the ongoing challenge, more data-sharing among homelessness data systems and jails, prisons, hospitals, emergency rooms, and law enforcement agencies is needed. To effectively address veteran homelessness requires a process that reflects the complexity of the issue, Leslie said: “Homelessness doesn’t occur in a silo. We interact with other broader systems that impact homelessness. We need to bridge the gaps, and data helps us do that.”14

Endnotes

- Pamela Kestner (deputy secretary, Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, and homeless outcomes coordinator), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 17, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Virginia Office of the Governor, “Governor McAuliffe Signs Agreement to Help End Veteran Homelessness,” news release, June 9, 2014, https://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=4936; Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness in 2015,” accessed Dec. 22, 2016, https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/Mayors-Challenge-Fact-Sheet.pdf. The Mayors Challenge initially also involved 77 cities and four counties.

- Matthew Leslie (director, housing development, Virginia Department of Veterans Services), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 13, 2016.

- Kestner interview.

- Leslie interview.

- Kelly King Horne (executive director, Homeward), interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, June 20, 2016.

- The Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing program (HUD-VASH) is a collaborative initiative that offers supportive housing to veterans, with HUD providing the housing vouchers and the VA providing the supportive services. Between the start of the program in 2008 through the end of 2016, more than 85,000 HUD-VASH vouchers have been awarded across the country. “HUD-VASH Vouchers” accessed March 1, 2017, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/vash.

- Connecticut and Delaware have also functionally ended veterans homelessness. U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, “Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness,” accessed Jan. 19, 2017, https://www.usich.gov/solutions/collaborative-leadership/mayors-challenge.

- Leslie interview.

- Ibid.

- Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Welcome to the Homelessness Data Exchange Website,” accessed Feb. 28, 2017, http://www.hudhdx.info/#pit. The Point-in-Time counts include sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness on a single night. Counts are provided by household type (individuals, families, and child-only households), and are further broken down by subpopulation categories, such as homeless veterans and people who are chronically homeless.

- Kathy Robertson, “Communities on the Cutting Edge of Ending Family Homelessness” (paper presented at the National Conference on Ending Family and Youth Homelessness, Oakland, California, Feb. 18–19, 2016), http://www.endhomelessness.org/page/-/files/Communities on the Cutting Edge of Ending Family Homelessness by Kathy Robertson.pdf.

- Ibid.