Missouri Policy Shortens Probation and Parole Terms, Protects Public Safety

Individuals on community supervision can earn credits to reduce their sentences

Overview

In 2012, Missouri established an “earned compliance credits” policy that allows individuals to shorten their time on probation or parole by 30 days for every full calendar month that they comply with the conditions of their sentences.1 Credits are available only to those who were convicted of lower-level felonies and have been under community supervision for at least two years.

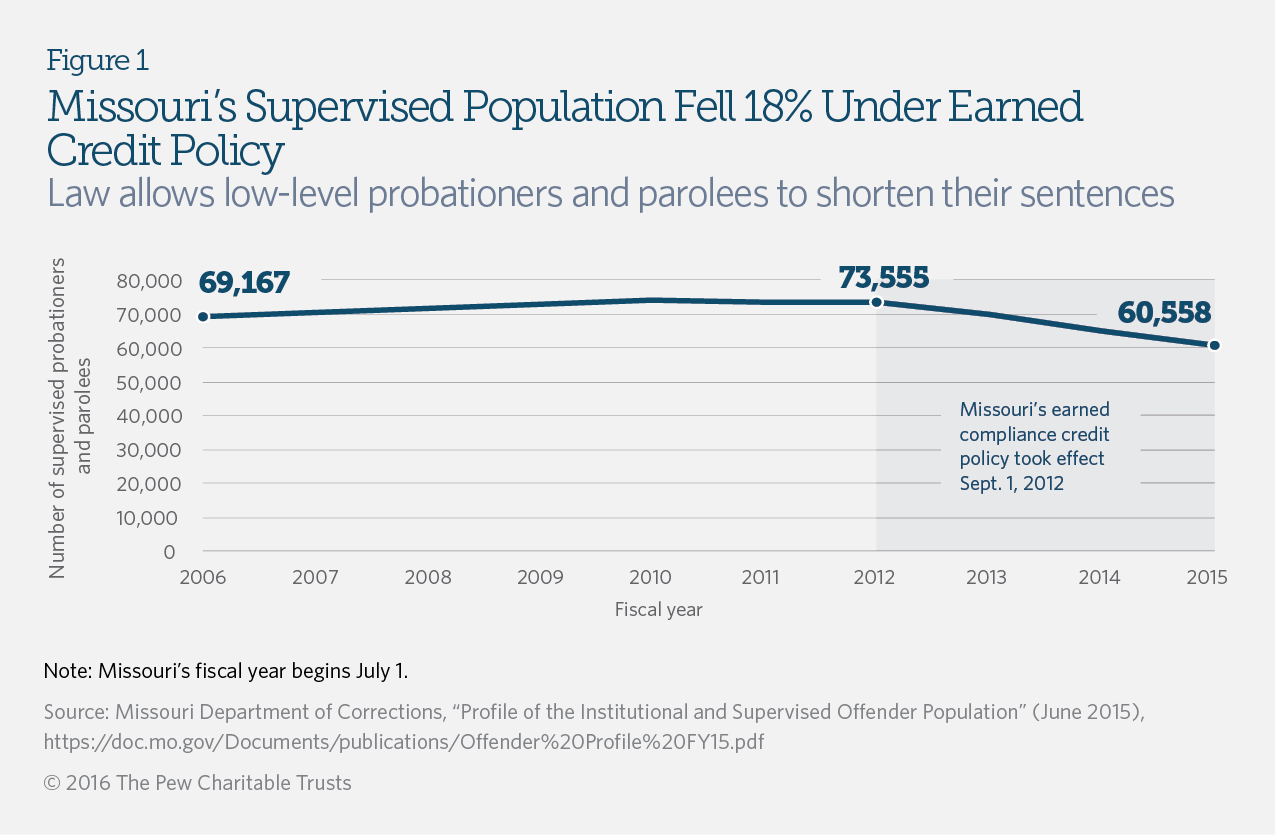

The Pew Charitable Trusts evaluated the policy and found that in the first three years, more than 36,000 probationers and parolees reduced their supervision terms by an average of 14 months.2 As a result, the state’s supervised population fell 18 percent, driving down caseloads for probation and parole officers. The law had no evident negative impact on public safety: Those who earned credits were subsequently convicted of new crimes at the same rate as those discharged from supervision before the policy went into effect.

Earned discharge

Missouri’s compliance credits are a form of “earned discharge,” a correctional practice that provides incentives to probationers or parolees to adhere to the rules of their supervision by reducing the length of their terms. Earned discharge is based on research showing that individuals on supervision respond best to a combination of rewards and sanctions.3 The American Probation and Parole Association, for example, said in a 2013 report that “to be most effective, correctional interventions with individuals involved in the justice system should consist of positive reinforcements that outnumber sanctions or punishments.”4

Interviews with parolees confirm that the prospect of early discharge provides a strong incentive to comply with monitoring conditions or to participate in correctional programming.5 For instance, a 2007 study of parolees found that “one of the strongest motivators” is the possibility of being released from supervision.6 In addition to encouraging compliance among those on supervision, earned discharge can reduce caseloads for probation and parole officers, allowing them to focus on individuals most at risk of reoffending.

Policies vary wildly by state

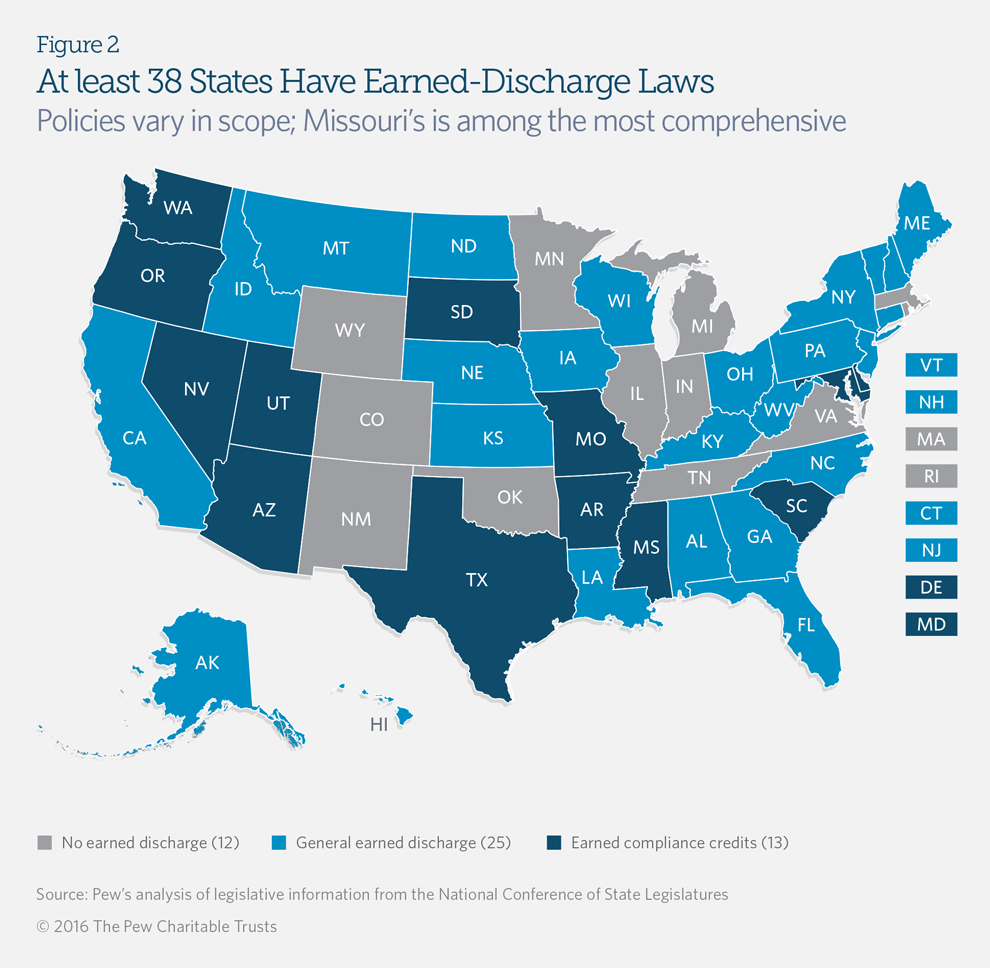

At least 38 states have some form of earned discharge, but their policies and practices vary considerably.7 (See Figure 2.) Twenty-five states have laws that allow courts or correctional authorities to grant earned discharge to certain individuals. Thirteen others, including Missouri, take a different approach, authorizing day-for-day credits or permitting eligible individuals to earn a set number of days off their sentences by completing drug treatment, behavioral counseling, or other programs.

Although most states make earned discharge available only to probationers, Missouri’s policy applies to parolees as well, significantly expanding its reach. The law creates a process by which compliance credits are automatically awarded to those who are eligible and have met all conditions. Such laws can streamline the discharge process by avoiding additional proceedings or hearings and can make the granting of credits swifter and more consistent across court or correctional districts.

To be most effective, correctional interventions with individuals involved in the justice system should consist of positive reinforcements that outnumber sanctions or punishments.American Probation and Parole Association

Missouri's earned compliance credits

Missouri established its policy as part of the 2012 Justice Reinvestment Act (H.B. 1525), which was intended to reduce the incarceration of individuals convicted of lower-level crimes and to invest the savings into alternatives that are shown to improve public safety outcomes.8 The act incorporated recommendations from the Missouri Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections, a bipartisan panel of lawmakers, judges, executive branch officials, and others who conducted a detailed review of the state’s correctional policies and practices in 2011. Pew provided technical assistance to the working group, including analysis and evaluation of the state’s corrections data.

Lawmakers in Missouri adopted the earned compliance credit policy in part because the state had a large supervised population, with many low-level probationers and parolees serving relatively long terms: an average of 53 months for probationers and 42 months for parolees in 2012, the year the law took effect.9 State legislators also intended the law to reduce the large number of people admitted to Missouri prisons each year as a result of probation or parole revocations.10

The policy took effect in September 2012, with the first early discharges occurring in October. Under the law, credits are available only to those who were convicted of a felony drug offense or a Class C or D felony, the two least severe categories, and have served at least two years under community supervision. The law excludes a range of people, including those on lifetime supervision and those convicted of certain crimes that are violent, sexual, or involve children. It also gives courts the discretion to reject others based on “the nature and circumstances of the offense or the history and character of the offender.” Approximately 75 percent of those on supervision are eligible for earned compliance credits.11

The impact of Missouri's policy

To assess the impact of the earned compliance credits, Pew obtained data from the Missouri Department of Corrections for more than 70,000 people discharged from probation or parole over an eight-year span. The group included:

- 27,925 who were discharged between September 2007 and August 2010, before the law took effect.12

- 36,526 who earned credits under the law and were discharged between October 2012 and August 2015.

- 7,658 who were discharged between October 2012 and August 2015 and were eligible for credits but did not earn them because of court refusal, the accrual of violations while on supervision, or other reasons.13

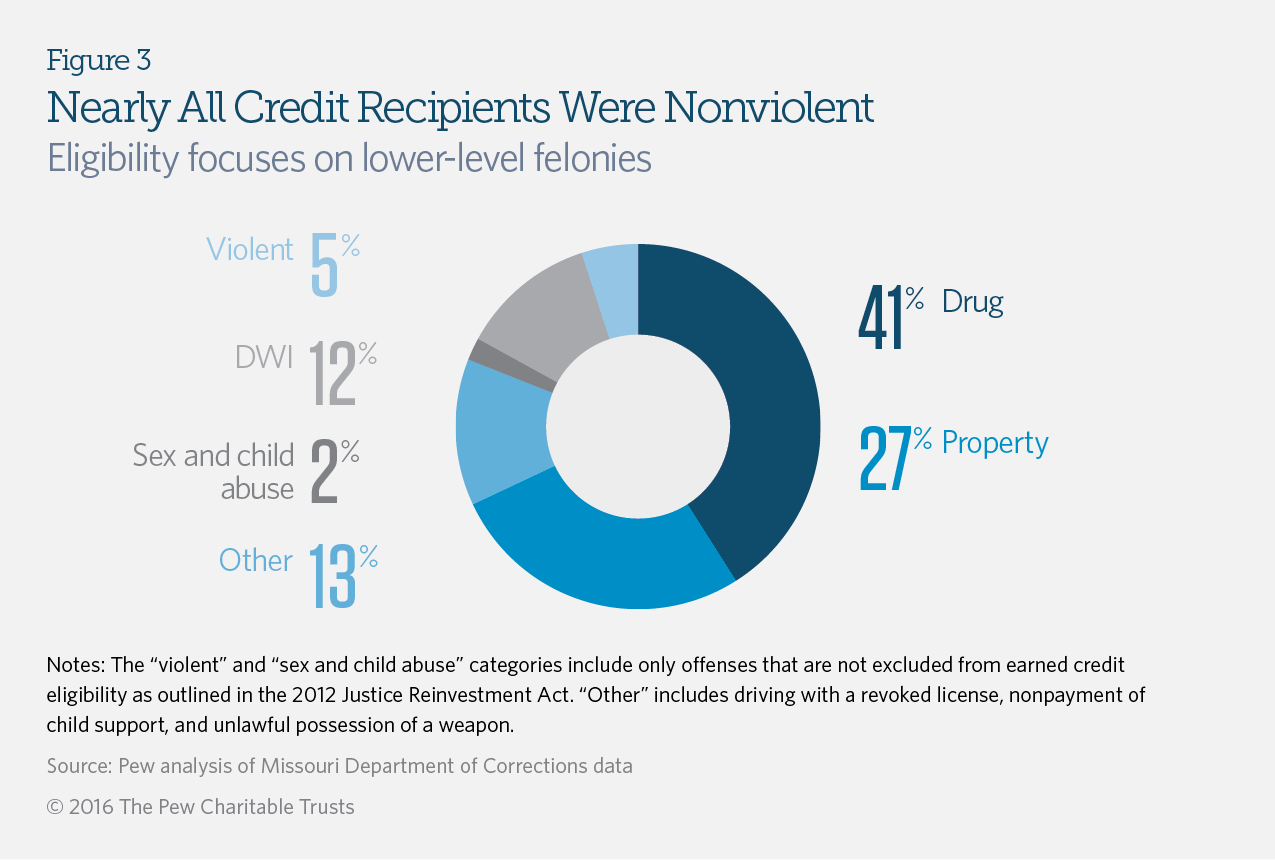

Most credit recipients were nonviolent

Pew’s analysis shows that individuals convicted of nonviolent offenses made up the overwhelming majority of the 36,526 individuals who earned compliance credits and were discharged between October 2012 and August 2015. Those convicted of drug offenses comprised 41 percent of the group, and those convicted of property crimes and driving while intoxicated accounted for 27 percent and 12 percent, respectively. (See Figure 3.) Ninety percent of those who earned credits were a low or medium risk to reoffend, according to a state assessment.

Credits significantly reduced length of supervision

Over the full evaluation period, probationers and parolees who earned compliance credits reduced their supervision terms by an average of 14 months. Pew’s analysis shows, however, that the average award increased over time and approached two years later in the evaluation period.14

- 12,821 individuals who were released between October 2012 and September 2013 earned an average of six months off their terms.

- 13,107 who were released between October 2013 and September 2014 earned an average of 15 months off their terms.

- 10,598 who were released between October 2014 and August 2015 earned an average of 22 months off their terms.

Supervised population and officer caseloads declined

Earned compliance credits helped reduce Missouri’s supervised population by 18 percent, or nearly 13,000 people, between August 2012 and June 2015, the most recent month for which data were available.15 The policy also helped decrease probation and parole caseloads. Officers managed an average of 59 supervisees in 2015, down from 70 in 2012.16

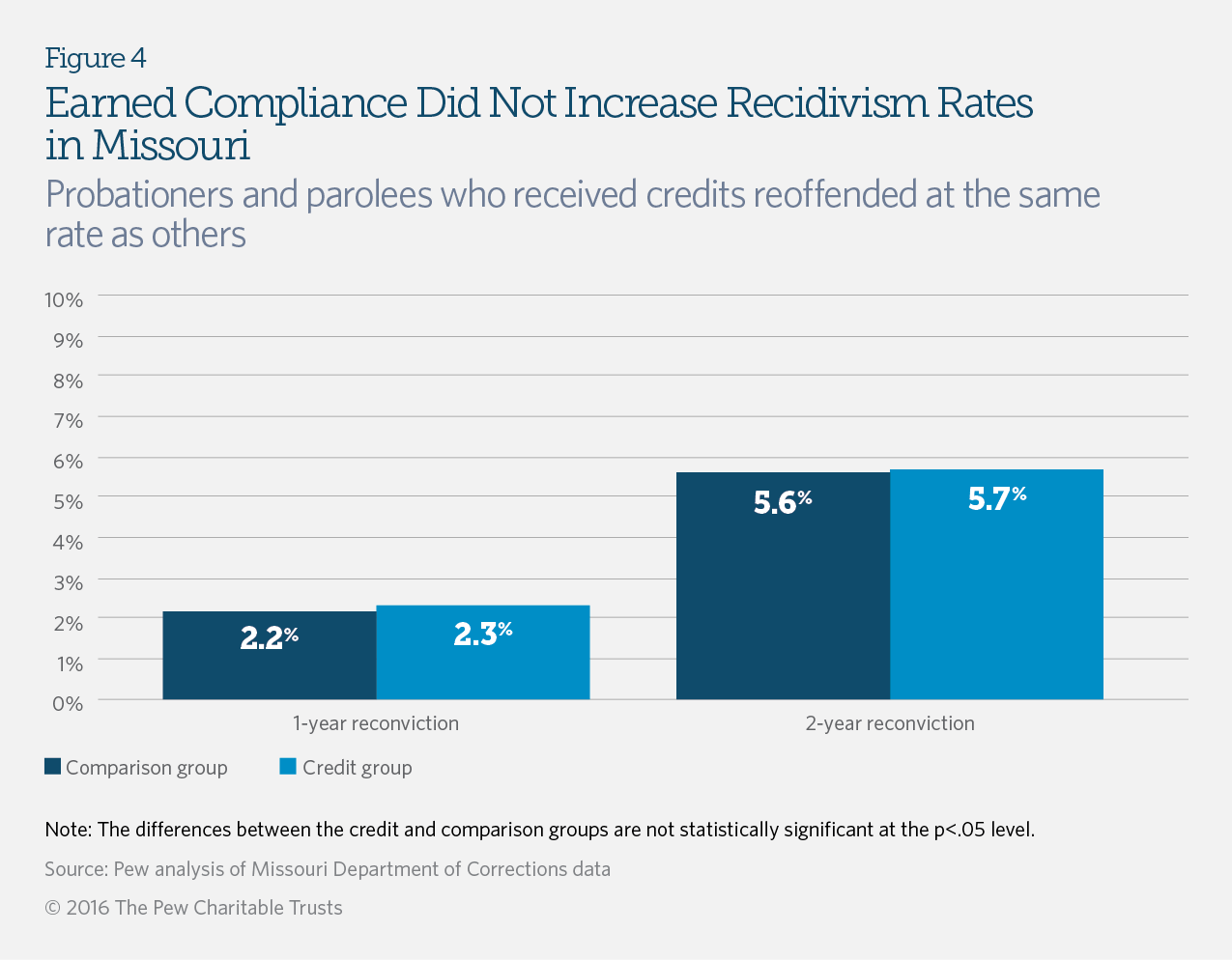

Recidivism rates did not change

To determine whether Missouri’s policy had any effect on recidivism, Pew compared re-conviction rates for a group of individuals who earned credits under the law with those of a group discharged from supervision before the policy went into effect. (See the methodology for details.) The analysis showed no statistically significant difference in recidivism rates between the two groups (See Figure 4.):

- 2.3 percent of those who earned credits had a new conviction within one year of discharge, compared with 2.2 percent of the comparison group.

- 5.7 percent had a new conviction within two years of discharge, compared with 5.6 percent in the comparison group.

The analysis also shows that nonviolent offenses made up the vast majority—87 percent—of the new crimes for which credit recipients were later convicted, effectively the same proportion as the comparison group.17

Conclusion

Since 2012, Missouri has allowed probationers or parolees to shorten their sentences through earned discharge, a correctional practice that encourages good behavior among those under community supervision. Three years of data show that the earned compliance credit policy significantly reduced the state’s supervised population without jeopardizing public safety. More than 36,000 individuals in Missouri shortened their probation and parole sentences by an average of 14 months through the law, with those who were discharged more recently earning reductions of nearly two years. Further, the availability of earned compliance credits had no effect on recidivism: Those who earned credits were subsequently convicted of new crimes at the same rate as those discharged from supervision before the policy took effect.

Earned compliance credits are one of a variety of policies that states are adopting to improve the performance of their sentencing and corrections systems. This evaluation demonstrates that such rewards can be a valuable tool to manage correctional populations.

Methodology

Pew compared recidivism rates for a group of individuals who earned compliance credits under Missouri’s law with those of a group discharged from supervision before the policy went into effect. To ensure the two groups were comparable in average age, sex, race, criminal history, risk level, and offense type, Pew employed propensity score matching, using a nearest-neighbor strategy with replacement and a caliper of 0.2. The analysis relied on a sample of 27,950 individuals to determine one- and two-year re-conviction rates for those discharged from supervision before Missouri’s credit policy began. It used a sample of 25,241 people to determine one-year re-conviction rates for those who participated, and a sample of 12,716 to determine their two-year re-conviction rates.

External reviewers

This brief benefited from the insights and expertise of Natasha Frost, Ph.D., associate professor and associate director for academic programs in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northeastern University; David Oldfield, director of research and evaluation at the Missouri Department of Corrections; and Brian Elderbroom, director of policy, research, and administration at Alliance for Safety and Justice. Neither they nor their organizations necessarily endorse the brief’s conclusions.

Acknowledgments

Pew would like to thank Christine Spinka from the Missouri Department of Corrections for providing the data and supplemental materials for this publication. Pew public safety performance project staff Kathryn Zafft, John Gramlich, Robin Olsen, Phil Stevenson, and Adam Gelb prepared the brief. Pew staff members Jennifer V. Doctors, Kelly Hoffman, Jennifer Peltak, and Liz Visser provided editing, design, and web support.

Endnotes

- Missouri Rev. Stat. § 217.703.1 (2012), http://www.moga.mo.gov/mostatutes/stathtml/21700007031.html. Unless otherwise noted, all details about Missouri’s earned compliance credit policy are drawn from the text of the statute.

- Unless otherwise noted, all findings about the outcomes of Missouri’s earned compliance credit policy are based on Pew’s analysis of data provided by the state Department of Corrections.

- Madeline M. Carter, Behavior Management of Justice-Involved Individuals: Contemporary Research and State-of-the-Art Policy and Practice, National Institute of Corrections (January 2015), https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/029553.pdf.

- American Probation and Parole Association, Effective Responses to Offender Behavior: Lessons Learned for Probation and Parole Supervision (2013), https://www.appa-net.org/eWeb/docs/APPA/pubs/EROBLLPPS-Report.pdf.

- Joan Petersilia, “Employ Behavioral Contracting for ‘Earned Discharge’ Parole,” Criminology & Public Policy 6, no. 4 (2007): 807–14, https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=242585.

- Ibid.

- Pew’s analysis of legislative information from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Public Safety in Missouri” (September 2012), http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2012/09/28/public-safety-in-missouri.

- Time served data refer only to probationers and parolees who would have been eligible for earned compliance credits, not to Missouri’s entire supervised population.

- Missouri Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections, “Consensus Report” (December 2011), 3, http://www.senate.mo.gov/12info/comm/special/MWSC-Report.pdf.

- David Oldfield, Missouri Department of Corrections, email message to Robin Olsen, The Pew Charitable Trusts, July 20, 2016.

- Pew evaluated probationers and parolees who were discharged from supervision at least two years before the earned compliance credit law took effect to allow for a sufficient follow-up period.

- Individuals whose supervision terms were scheduled to end shortly after the state policy took effect may not have had the opportunity to earn credits.

- The average award increased over time because individuals who were already on supervision when the policy took effect had less time to earn credits and, therefore, to substantially reduce their sentences than those who began supervision after September 2012.

- Missouri Department of Corrections, “Profile of the Institutional and Supervised Offender Population” (June 2015), https://doc.mo.gov/Documents/publications/Offender Profile FY15.pdf.

- David Oldfield, Missouri Department of Corrections, email message to Kathryn Zafft, The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 3, 2016. Probation and parole officer staffing levels did not change. Pew did not analyze the fiscal impact of the earned compliance credits because the policy did not affect staffing costs and other budgetary information was not a part of the data collection.

- The difference between the compliance credit group and the comparison group is not statistically significant using a two-sample t-test with a significance level of p<0.05.