Curbing Prescription Drug Abuse With Patient Review and Restriction Programs

Learning from Medicaid agencies

© Getty Images

© Getty ImagesUpdates

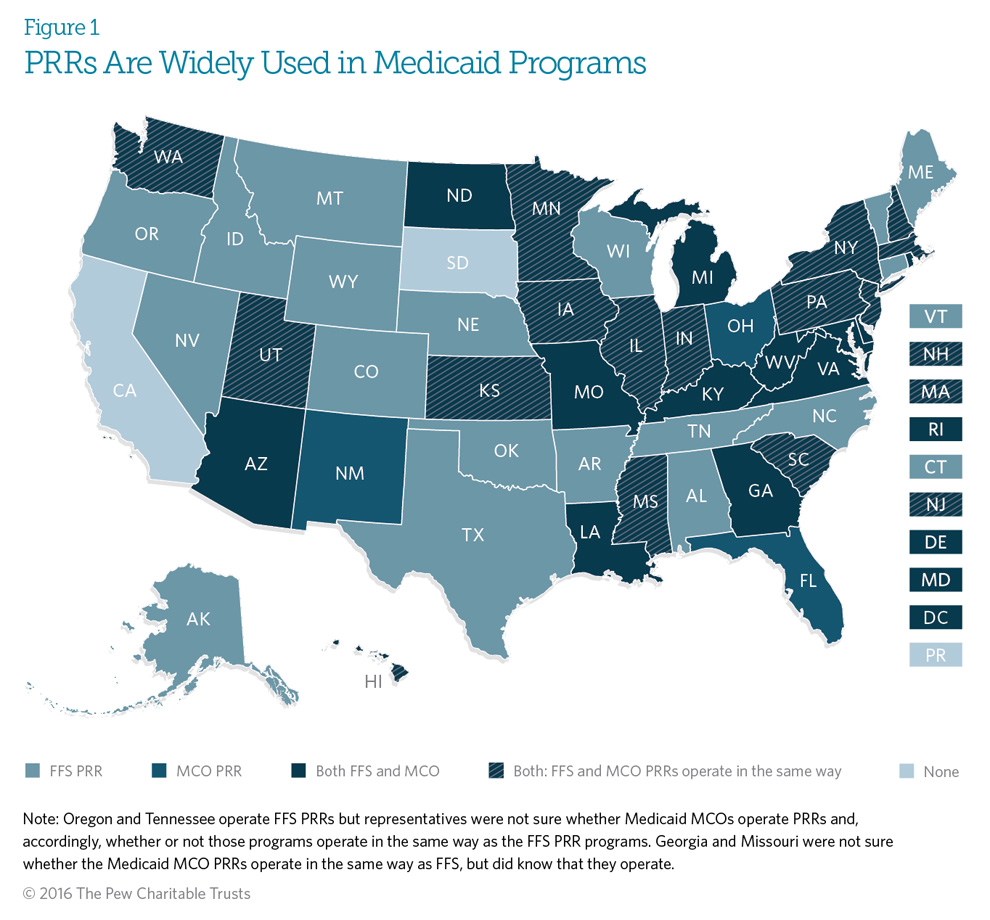

Michigan clarified that its Fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) program began in 1979, not 2014, as originally noted. Figure 2 was updated April 6, 2016, to reflect this.

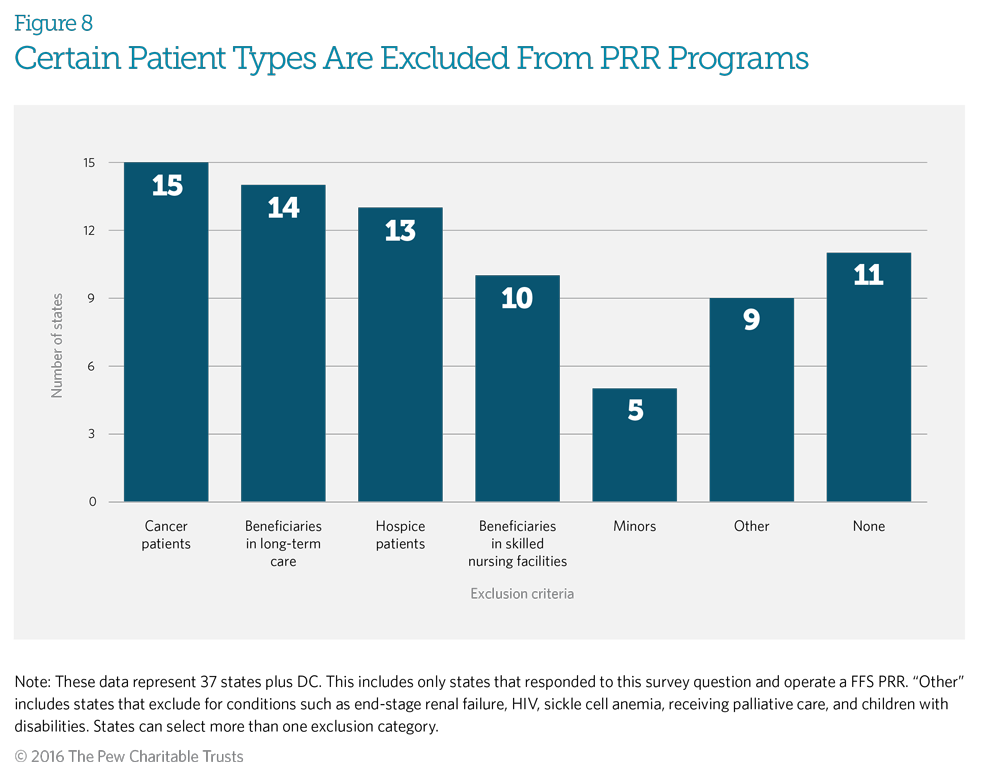

Oregon provided updated information on specific patient groups automatically excluded from PRR enrollment. Figure 8 was updated July 18, 2016, to reflect this.

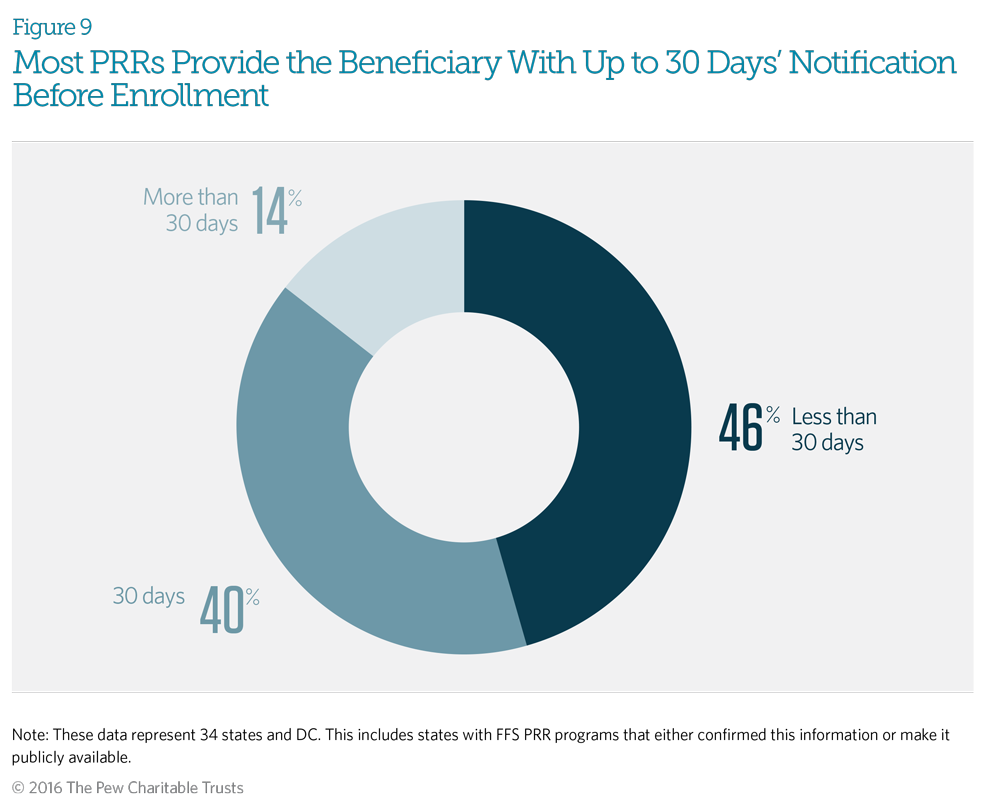

Missouri, Nevada, and Virginia provided updated information on the beneficiary notification process. Figure 9 was updated July 18, 2016, to reflect this.

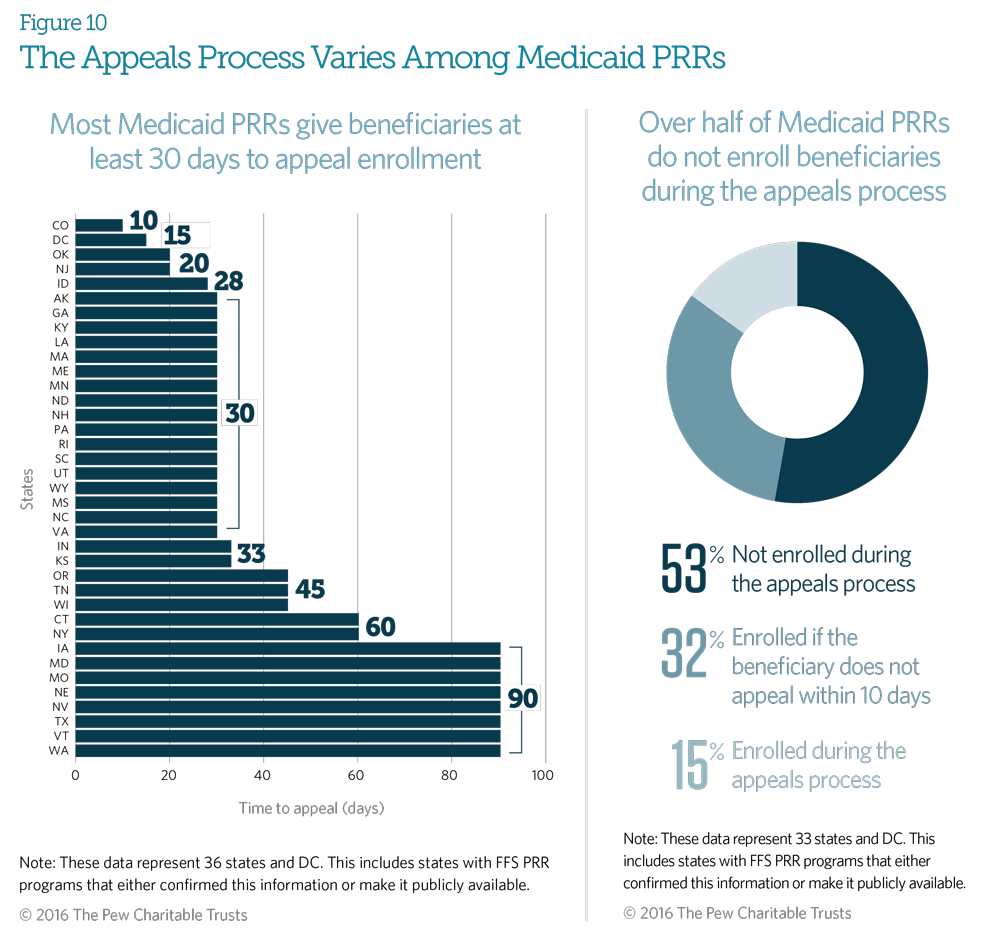

Maryland, Nevada, and Virginia provided updated information on the appeals process. Figure 10 was updated July 18, 2016, to reflect this.

Maryland provided updated information on drugs managed by the PRR program. Figure 15 was updated July 18, 2016, to reflect this.

Alaska clarified that its PRR program began in 1985, not 2005, as originally noted. Figure 2 was updated Jan. 4, 2017, to reflect this.

Glossary of Definitions

Fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid program. Medicaid provides patient care through FFS or managed care delivery models. FFS Medicaid programs reimburse health care providers for each service that is performed and billed, such as office visits, diagnostic tests, and procedures.

Managed care Medicaid program. Medicaid managed care offers health benefits through contracted arrangements between Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations that agree to accept a set payment per member per month for all contracted services. However, managed care organizations generally pay the provider on a FFS basis and absorb the loss if actual overall costs exceed costs projected under the contract.

Point-of-sale edits. Point-of-sale edits occur when the plan includes safety controls (e.g., a maximum cumulative dose or maximum days of therapy) resulting in an alert that prevents the filling of a prescription until the pharmacy, prescriber, or patient has addressed the concern.

Prior authorization. Prior authorization requires the prescriber or pharmacy to provide the insurer with information demonstrating medical necessity before dispensing the drug.

Quantity limits. Quantity limits are predetermined quantities of a drug that may be dispensed in a period of time. These limits are frequently used to promote a drug’s safe use.

Overview

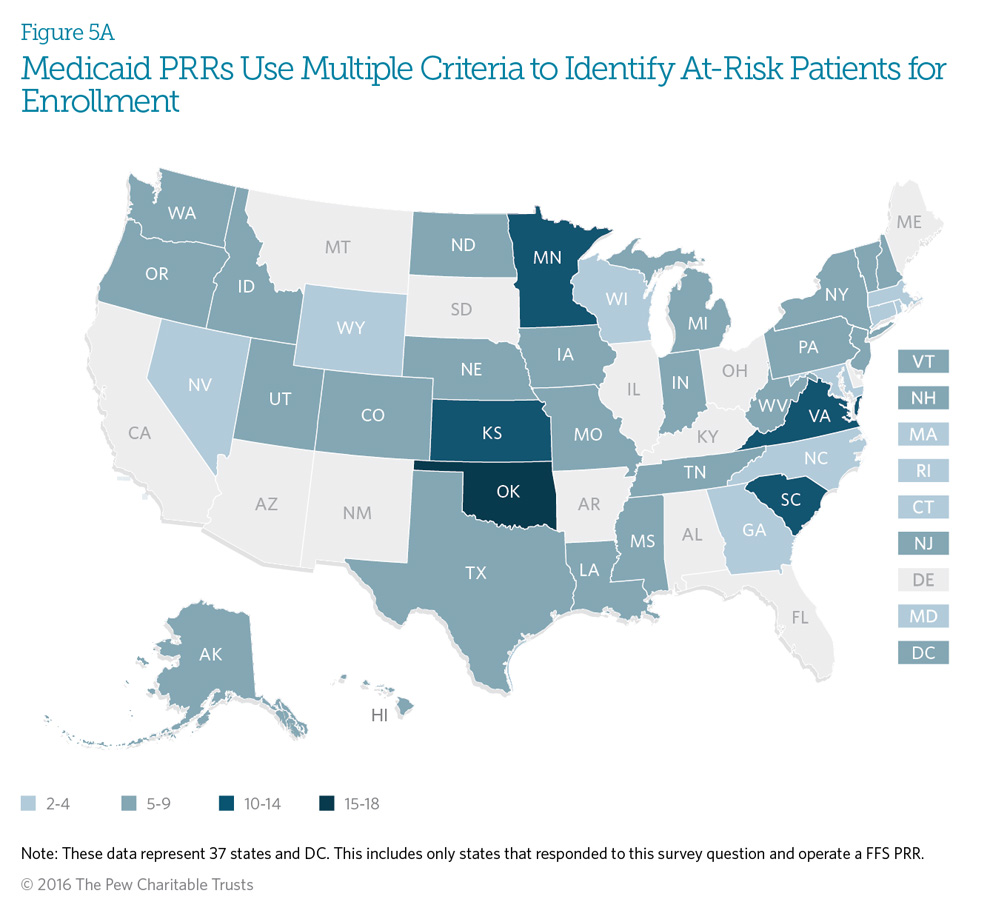

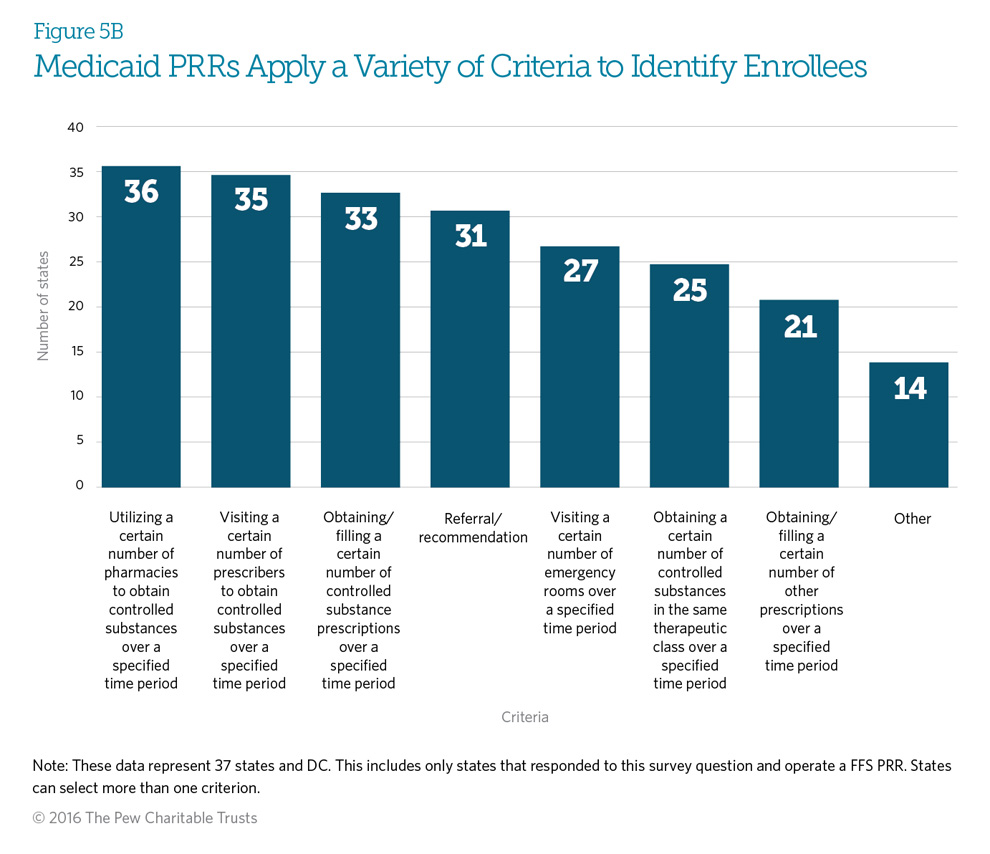

To minimize overdoses and other harms associated with prescription drug abuse, public and private insurance plans are using patient review and restriction (PRR) programs to encourage the safe use of opioids and other controlled substances. Through PRRs, insurers assign patients who are at risk for drug abuse to predesignated pharmacies and prescribers to obtain these drugs. Insurers identify at-risk patients based on a combination of criteria that are unique to each Medicaid PRR. Common criteria include the number of prescribers and pharmacies a patient visited to obtain controlled substance prescriptions (for more information on criteria, see Figures 5A and 5B). Designated medical providers can then better coordinate patient care and prevent inappropriate access to medications that are susceptible to abuse. More than 19,000 people in the United States die each year from prescription opioid overdoses.1 PRR programs have the potential to save lives and lower health care costs by reducing opioid usage and minimizing potential harms.2

This chartbook presents the results of a nationwide survey of Medicaid PRR programs, providing an overview of program characteristics, structures, and trends across 43 states. (See Appendix A for the complete methodology.) It found variation in the type of PRR offered, the criteria used to identify patients for enrollment in the programs, and program details such as how pharmacies or providers are assigned and the structure of patients’ appeal rights. In almost all responding states, PRRs were one of several tools used to prevent prescription drug abuse.

States can use this chartbook as a resource to guide program improvements. It provides insights on program characteristics and should serve as a starting point for encouraging state-to-state dialogue between Medicaid agencies and among other stakeholders. These efforts may lead to the development of best practices for PRRs as part of an overall drug abuse prevention strategy. For each state’s specific information, see Appendix B for program criteria used to identify at-risk patients for PRR enrollment, Appendix C for the clinical review process, and Appendix D for the patient review process for release from the program.

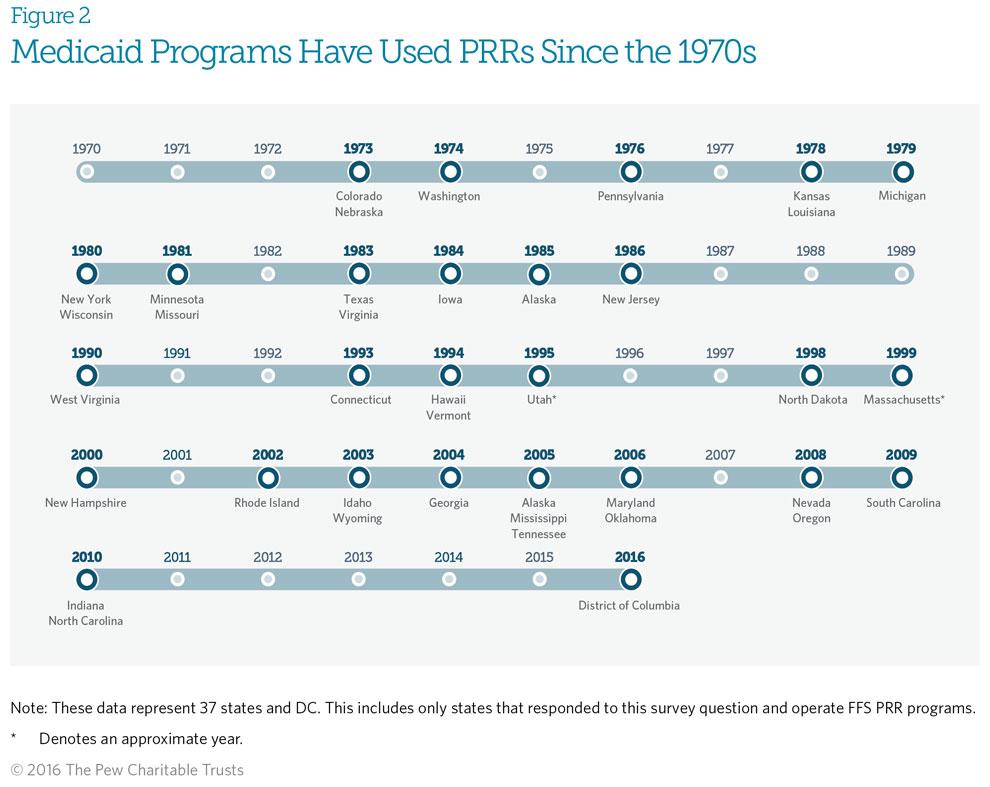

Of 52 U.S. Medicaid programs, including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, 49 operate a patient review and restriction (PRR) program for their fee-for-service (FFS) population, managed care organization (MCO) population, or both* (see Glossary of Definitions for definitions of FFS and managed care programs). Twenty-eight states operate PRRs in both Medicaid FFS and managed care environments; 16 states administer PRRs only in Medicaid FFS; and three states administer a PRR only in Medicaid managed care. Two other states also operate a FFS PRR, but respondents could not confirm whether the Medicaid managed care plans in these states have active PRRs.

Fifty-four percent of states operating a PRR in both Medicaid FFS and managed care indicated that state law or regulation requires their managed care PRRs to follow the same program structure as their FFS PRRs, including use of the same criteria for identifying potentially atrisk beneficiaries for PRR enrollment.

*California, South Dakota, and Puerto Rico do not operate Medicaid PRR programs.

Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) patient review and restriction (PRR) programs have been in operation since the early 1970s, but some are as new as 2016. Start dates for the 38 FFS PRR programs that responded to this survey question ranged from 1973 to 2016.* Colorado and Nebraska were the first states to start operating a PRR, in 1973. It should be noted that Colorado’s PRR has limited operational capacity; it is being redesigned, with plans to implement in the summer of 2016. The District of Columbia has PRRs in place within its Medicaid managed care plans, but its FFS PRR is not yet active. It is also expected to begin operating in 2016.

*The time frame includes states that plan to launch PRRs in 2016.

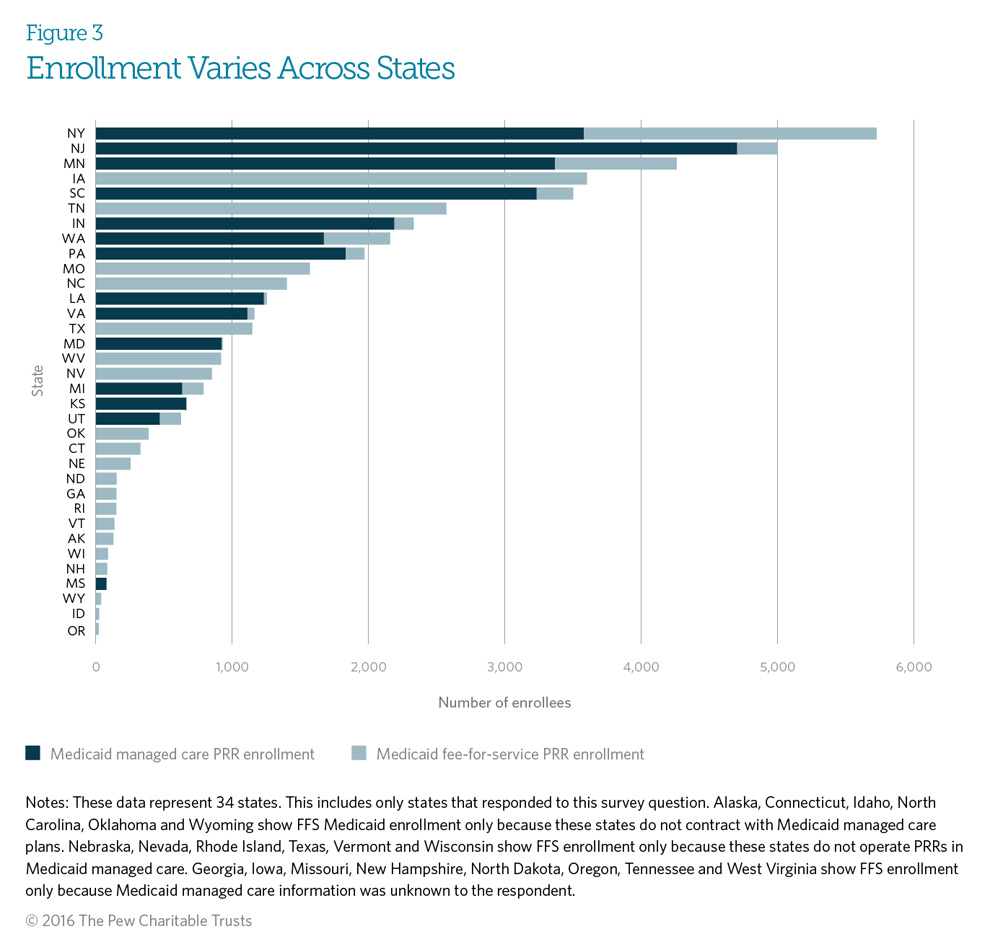

In 2014, the number of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid patient review and restriction (PRR) programs varied substantially among states, from as few as 19 in Oregon to over 5,700 in New York. Differences in the size of states’ Medicaid populations alone do not explain the variation in enrollment. For example, Texas has over 3.8 million Medicaid enrollees but a PRR program with only 1,145 enrolled beneficiaries. This PRR population approximately equals that in states such as Maryland and Virginia, which have much smaller Medicaid populations (1.1 million and 938,184, respectively).3 Other factors, such as a state’s rate of prescription drug abuse, extent of Medicaid program resources, and number and type of criteria used to identify at-risk patients, may also contribute to state variation in PRR enrollment. States may want to re-examine their individual circumstances to determine whether changes are necessary to achieve PRR program objectives.

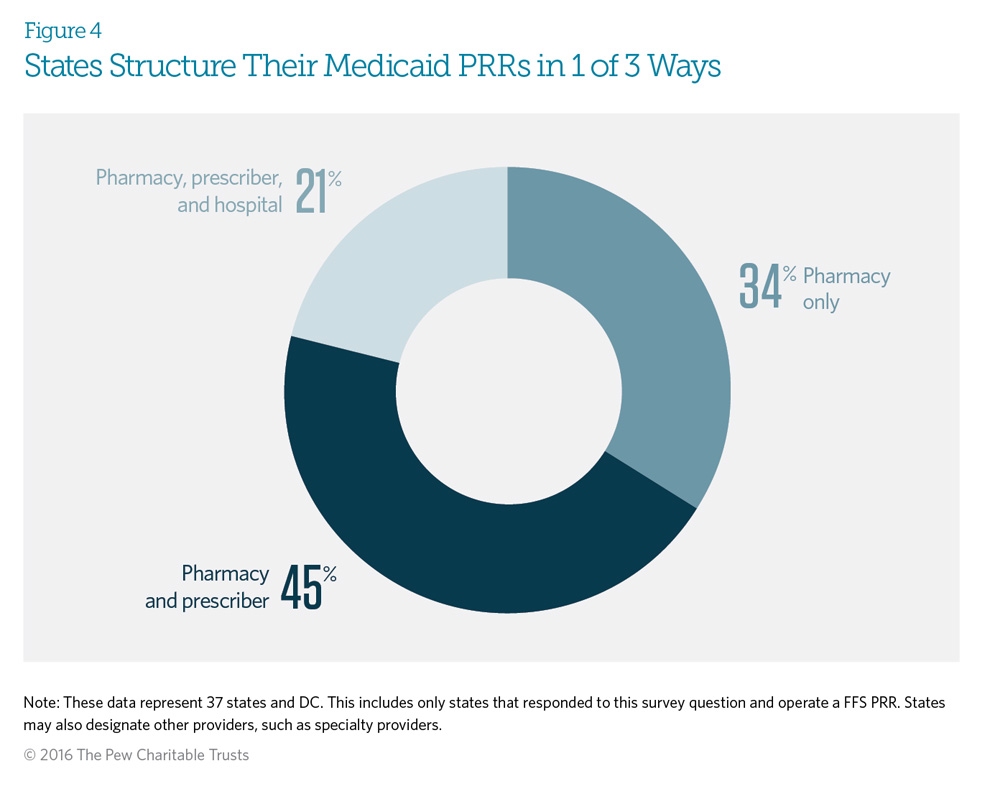

Medicaid patient review and restriction (PRR) programs typically require at-risk enrollees* to receive controlled substance prescriptions from either a designated pharmacy and prescriber or a designated pharmacy only. All states responding to this survey question indicated that the fee-for-service PRR designates a pharmacy, at least, for the at-risk enrollee. Further, the state may designate other providers, such as dentists or pain management providers, if it determines that the patient has over-utilized such services.

*These are beneficiaries who have been identified using specific criteria, such as seeing multiple prescribers or pharmacies and obtaining a large number of opioid prescriptions. (See Figures 5A and 5B.)

Medicaid patient review and restriction (PRR) programs use specific predetermined criteria to identify potentially at-risk beneficiaries. All of the surveyed states with fee-forservice programs indicated that they use at least two criteria to identify beneficiaries. Seventy-six percent of programs use at least five criteria, and 13 percent use over 10 criteria to identify at-risk beneficiaries.

Twenty-nine responding states (76 percent) use all three of the most commonly used criteria (utilizing a certain number of pharmacies, using a certain number of prescribers, and obtaining a certain number of controlled substance prescriptions over a specified time period) to identify potentially at-risk beneficiaries. Fourteen states (37 percent) use the seven criteria defined in the graph. See Appendix B for each state’s specific program criteria.

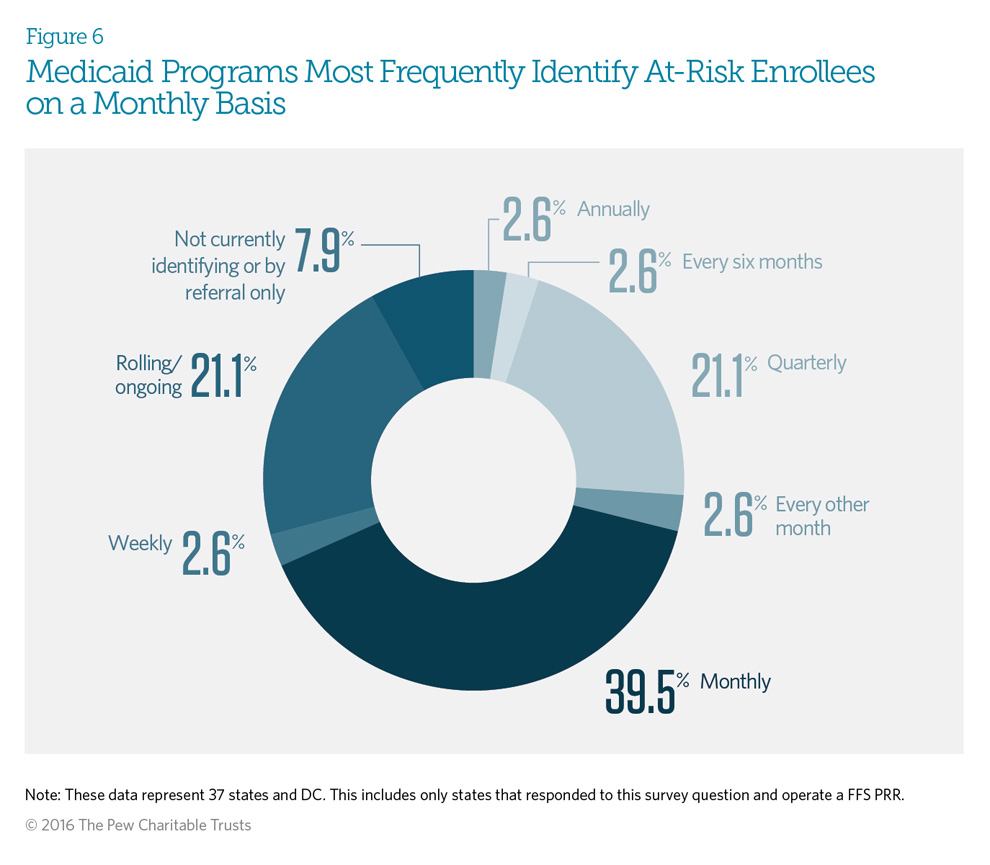

Sixty-three percent of the Medicaid fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) programs that responded perform claims data analysis to identify potentially at-risk enrollees on at least a monthly basis (monthly, weekly, or rolling/ ongoing). Only three states—Idaho, Texas, and Washington—are not currently identifying new patients, or are identifying patients via referral only, because of limited program resources.

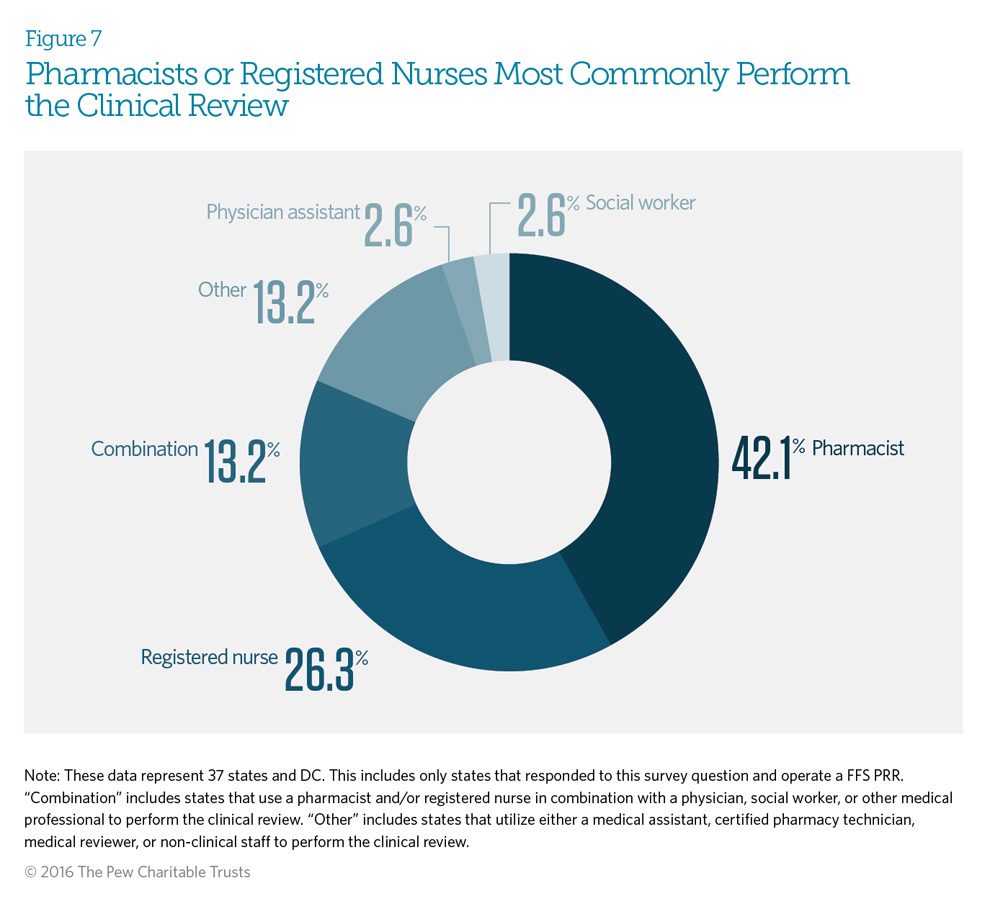

After potentially at-risk beneficiaries are identified using predetermined criteria, Medicaid patient review and restriction (PRR) programs review a beneficiary’s claims history for prescription drugs. If the clinical review determines that the drug use is appropriate, plan administrators will not enroll the beneficiary in a PRR program. Eighty-two percent of Medicaid fee-for-service PRRs use pharmacists or registered nurses to perform the clinical review (this includes the category defined as combination). Thirteen percent of PRRs use a combination of pharmacists, nurses, social workers, physicians, or other medical professionals to perform the review. New York requires that a pharmacist, registered nurse, and physician all review a beneficiary’s claims history before enrolling the patient in a PRR. See Appendix C for each state’s specific clinical review process.

Patients, such as those receiving treatment for certain types of cancer, in hospice, or in long-term care, are typically excluded from PRR programs. Fifteen Medicaid fee-for-service PRR programs exclude from enrollment patients receiving treatment for certain cancers, with 10 states excluding both certain cancer patients and those in hospice care. Six of these programs also exclude patients who are in long-term care, in addition to patients in hospice care and those receiving treatment for cancer. These exclusions help ensure that patients with medical needs have access to effective pain management. Although 11 states indicated that they do not automatically exclude beneficiaries from enrollment, they may choose to do so if the clinical review determines that the medication use is appropriate for these patients’ health conditions.

Beneficiaries receive notice, usually written, of their identification for inclusion in a patient review and restriction (PRR) program before their enrollment occurs. The notification explains the beneficiary’s right to appeal. Most programs also provide beneficiaries with instructions on how to give input on designated providers. Most responding fee-for-service PRRs indicated that their staffs provide beneficiaries with written notification up to 30 days before enrolling the patient in the PRR. Only two states—Connecticut and West Virginia—give beneficiaries 60 or more days’ notice.

Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) patient review and restriction (PRR) programs allow patients to appeal their identification as at-risk and their subsequent PRR enrollment and provide the right to a fair hearing. Eighty-six percent of responding PRRs give the beneficiary at least 30 days from notification to appeal the decision; 27 percent provide at least 60 days.

Fifty-three percent of states responding will not enroll the beneficiary in the PRR during the appeals process, and 32 percent will enroll the beneficiary if the beneficiary does not appeal within 10 days of notification.

Seventy-two percent of programs responding (24 out of 33 states) indicated that no beneficiaries appealed their at-risk status and PRR enrollment in the FFS PRR programs for 2014. These states’ PRR enrollment numbers range from 22 to 5,000. (These data are not shown.)

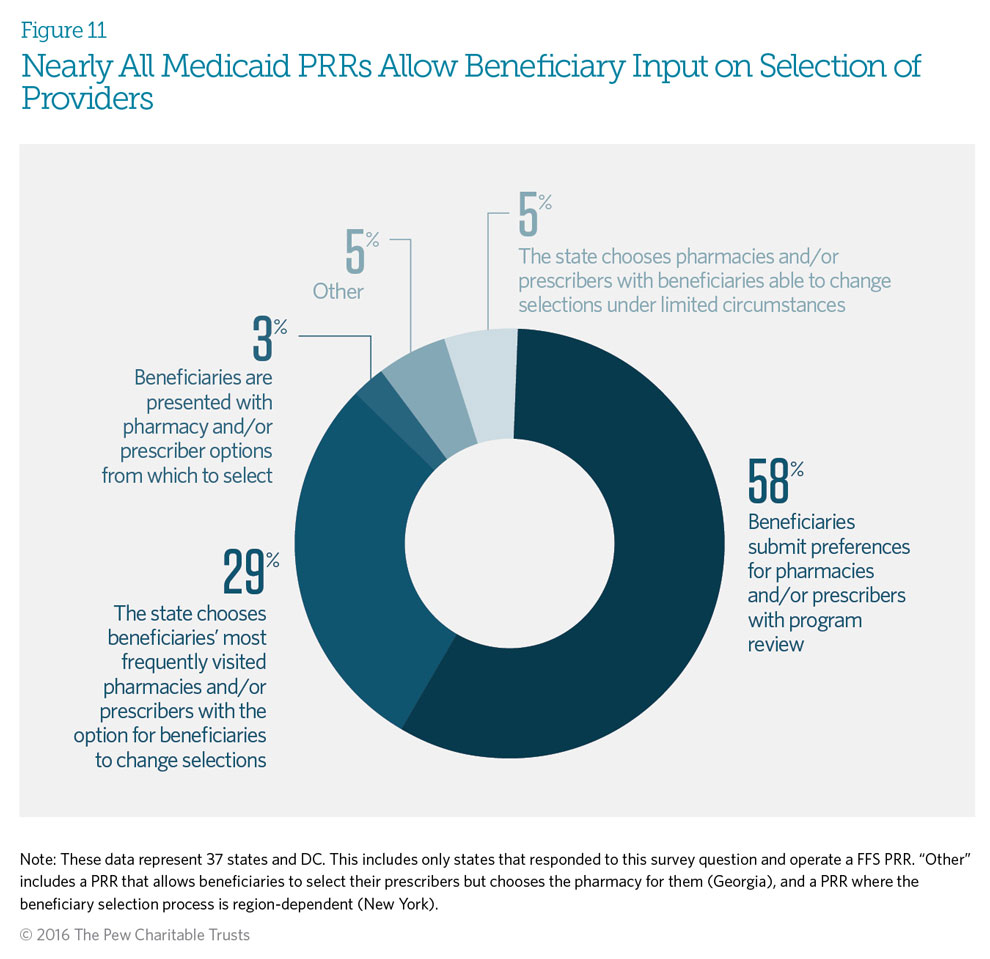

Ninety-five percent of responding Medicaid fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) programs allow beneficiaries to have some input on the selection of providers. Fifty-eight percent of PRRs allow beneficiaries to submit provider preferences before these designations are made. PRR programs will review a beneficiary’s selection of providers to ensure that they are not contributing to abuse before confirming designation. If the beneficiary does not respond, states may choose the beneficiary’s most frequently visited providers. Only 5 percent of state programs choose providers for beneficiaries, with limited opportunity for the beneficiaries to change them.

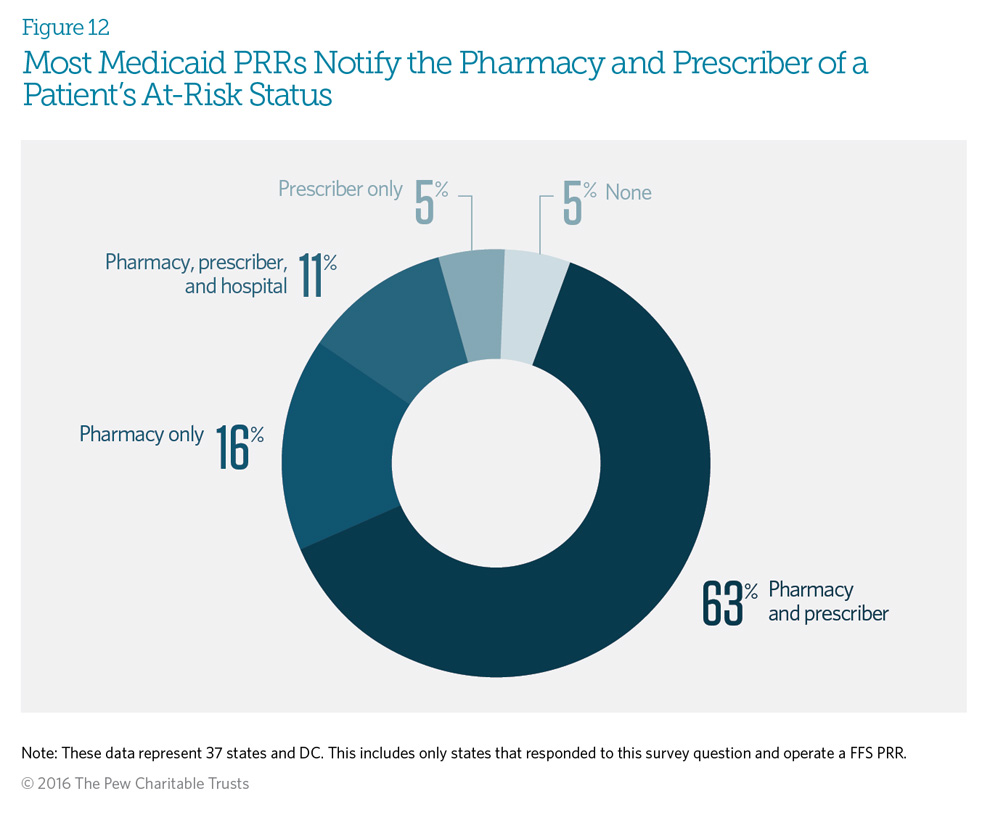

Almost all of the responding Medicaid fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) programs will notify at least one of the selected providers of a patient’s enrollment in the PRR. Sixty-three percent notify both the beneficiary’s pharmacy and prescriber. Six of those states—Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wyoming—indicated that although they operate pharmacy-only PRRs, they notify both the pharmacy and the prescriber of the patient’s at-risk status and pharmacy designation. The 16 percent of programs that notify the pharmacy only operate pharmacy-only PRRs.

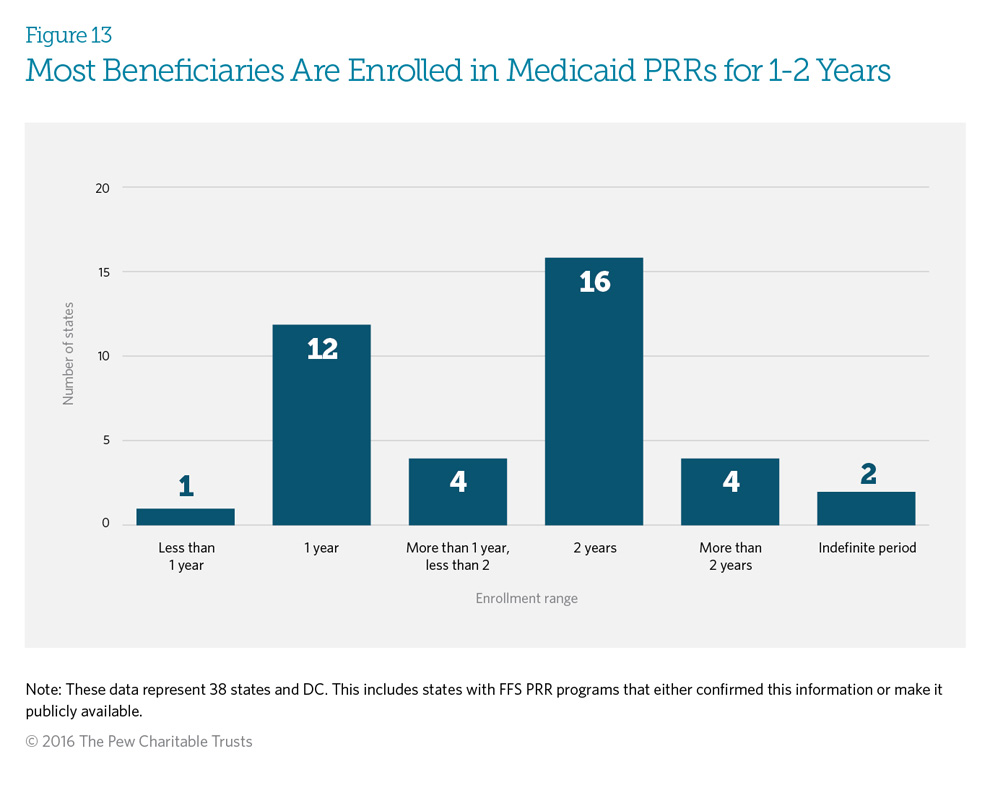

Medicaid fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) programs typically enroll beneficiaries for a fixed time frame. At the end of that time, patients are assessed for re-enrollment based on a patient review. Forty-one percent (16 programs) of responding PRRs enroll their beneficiaries for 24 months, while 31 percent (12 programs) enroll them for 12 months. Three states—New York, Texas, and Wyoming—will enroll beneficiaries for increasing increments of time if re-enrollment in a PRR is indicated. Two states—Nevada and Tennessee—enroll beneficiaries for an indefinite period, and two states—Georgia and Missouri— have maximum enrollment periods. Once the beneficiary has met the maximum time frame, he or she is released from the PRR. The patient review occurring at the end of the initial term includes assessing the use of controlled substances to determine whether the patient still requires PRR enrollment to prevent inappropriate drug use. See Appendix D for each state’s specific patient review process.

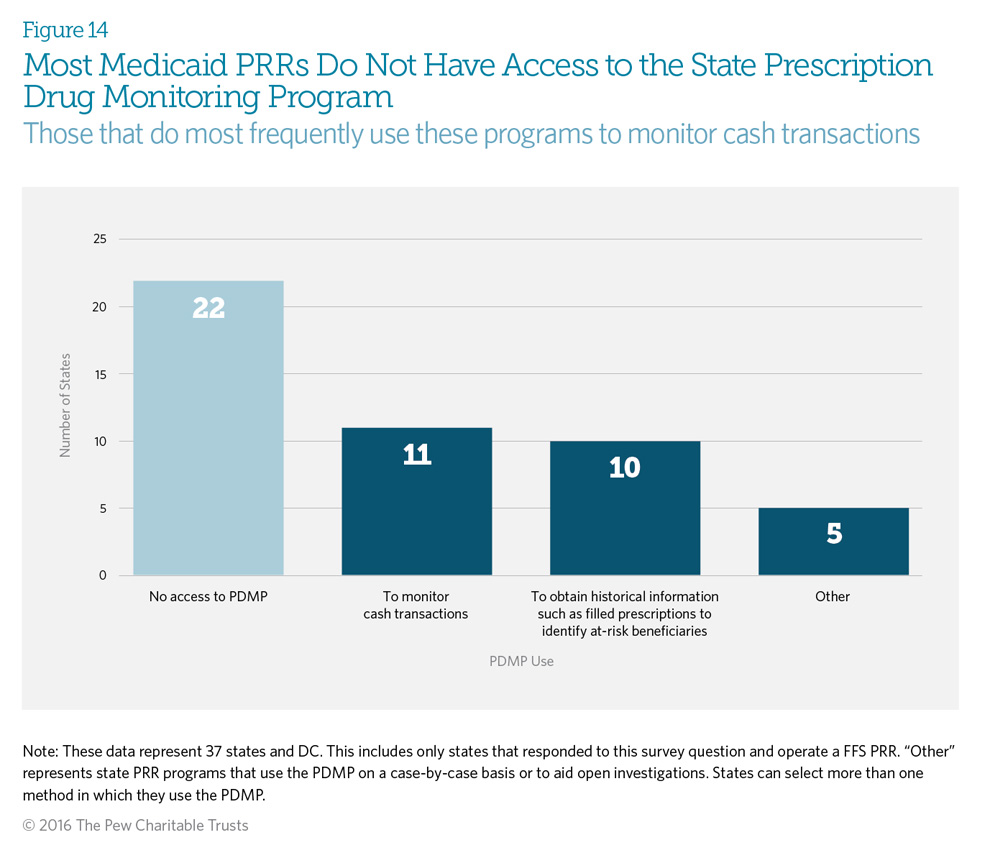

Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are state-run electronic databases that monitor dispensed prescriptions for controlled substances. PRRs can use information from state PDMPs for several purposes, such as monitoring cash transactions and identifying at-risk beneficiaries for potential enrollment in the PRR. Fifty-eight percent of respondents (22 states) indicated that their Medicaid fee-for-service PRR program does not have access to the state PDMP. State laws governing 32 of 50 PDMPs* allow insurers to access the PDMP, but this allowance may not be implemented in all states.4

Sixty-nine percent of states that have access to the PDMP use it to monitor cash transactions. This is useful, because data available to the PRR program allow verification only of services billed through that insurer. The patient could be paying cash to see other providers in order to obtain controlled substance prescriptions; only the PDMP is able to identify these transactions.

*Includes the District of Columbia PDMP, which is not yet in operation.

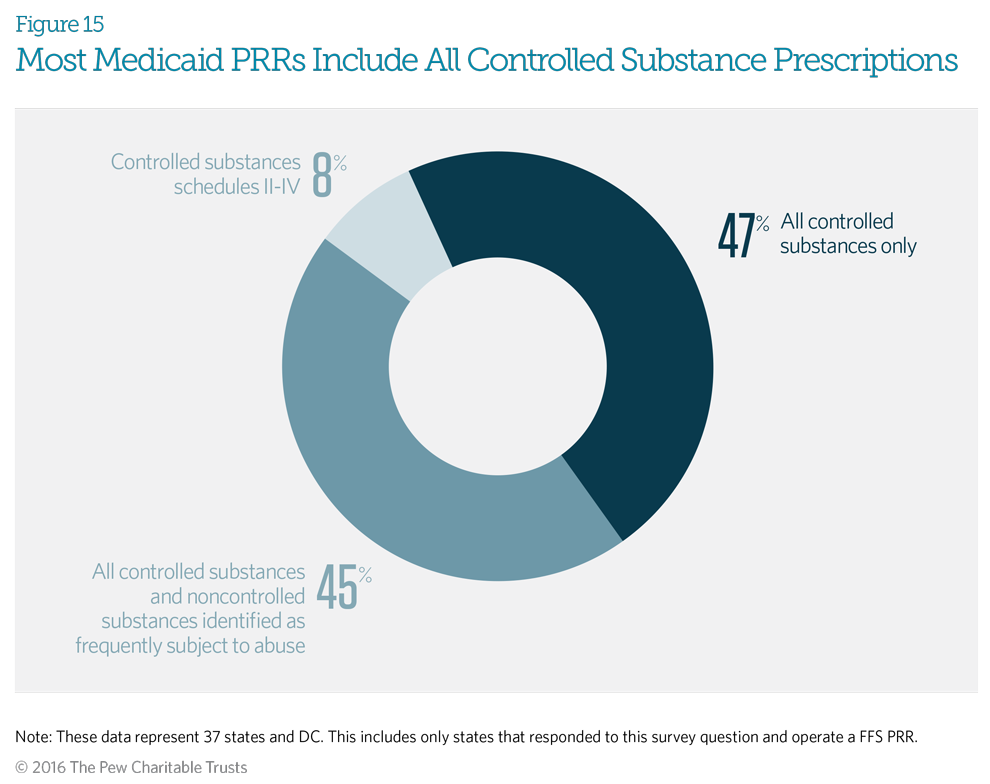

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies controlled substances in five distinct schedules determined by whether the drug has acceptable medical uses and its potential for abuse or dependency. Schedule I includes only illicit drugs with no accepted medical use; all prescription controlled substances are in schedules II-V. Ninety-two percent of responding Medicaid fee-for-service patient review and restriction (PRR) programs indicated that their PRR covers all controlled substances in DEA schedules II-V. In addition to covering all controlled substances, 45 percent of states also include non-controlled drugs identified by that program as frequently subject to abuse, such as those used to treat HIV.5 This means that enrolled beneficiaries will obtain all controlled substances, as well as identified non-controlled substances, through their designated providers. Just three Medicaid PRR programs— in Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia—do not include controlled substances from Schedule V.

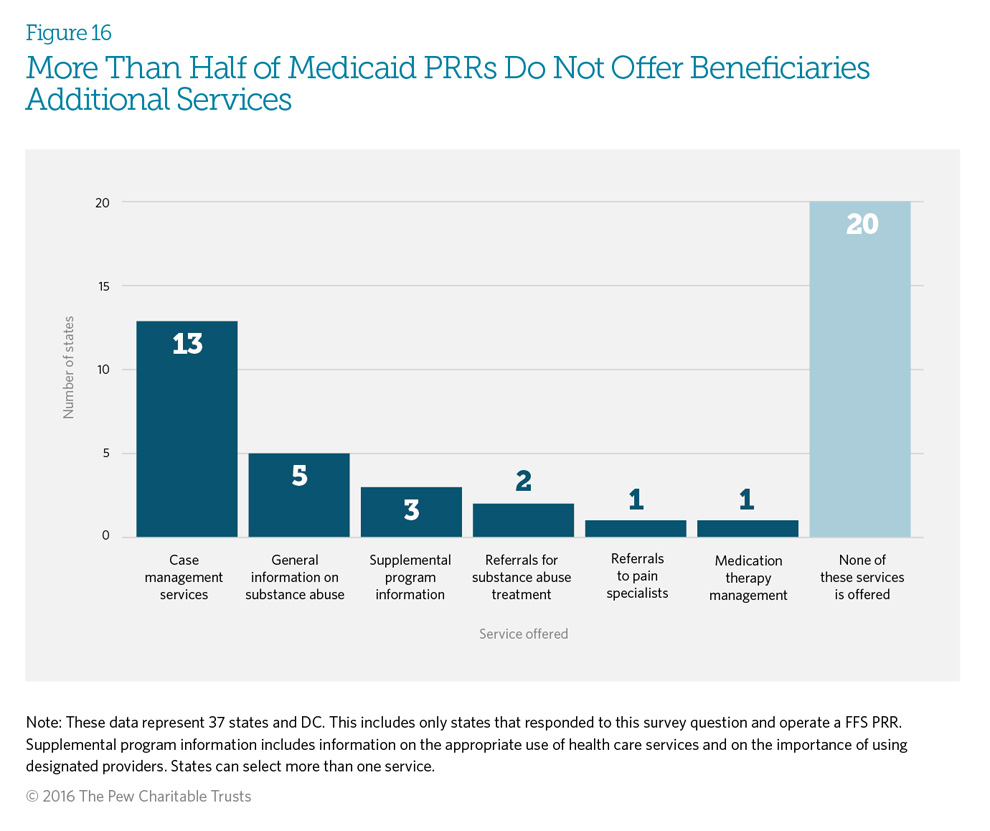

Twenty of the responding states (53 percent) indicated they do not offer any other services related to the patient’s use of pain management drugs. However, 18 states (47 percent) offer additional services to support beneficiary needs, with 34 percent (13 states) offering case management services.

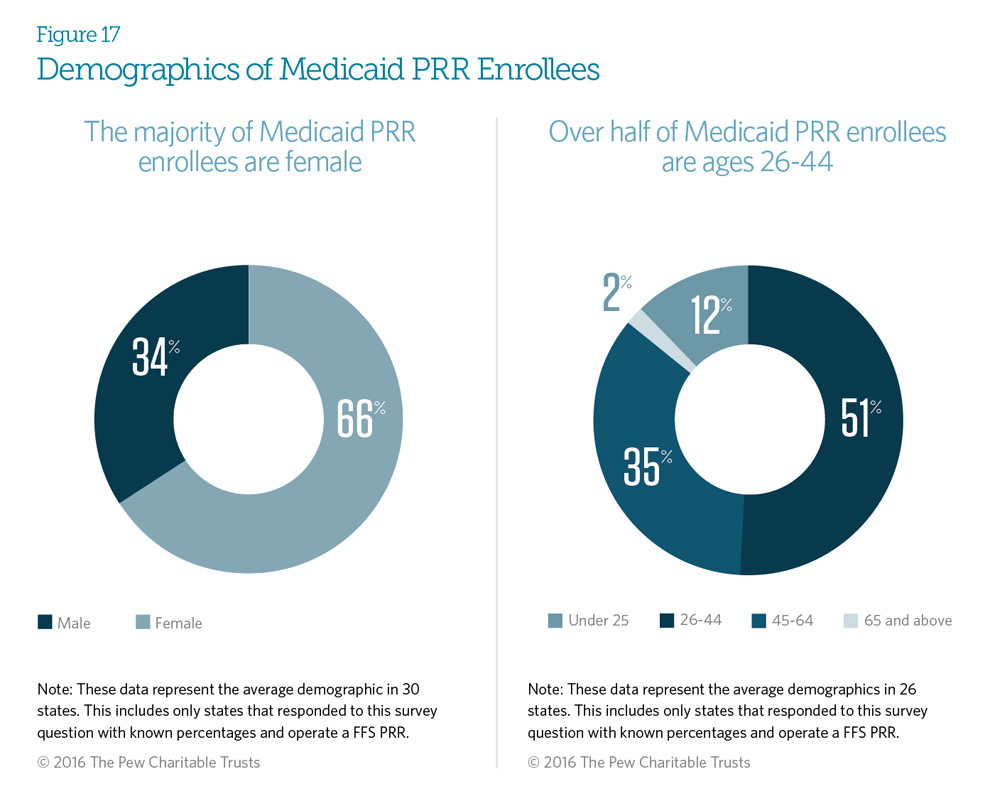

On average, 66 percent of Medicaid fee-for-service enrollees in patient review and restriction (PRR) programs are female. This female majority existed in 19 states. There were seven exceptions, with four states—Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York—having, on average, 70 percent male enrollees, and three states—New Hampshire, Oregon, and Vermont—with enrollment divided almost evenly between genders.

On average, 51 percent of FFS PRR enrollees are ages 26 to 44. Thirty-five percent are ages 45 to 64, and only 2 percent are age 65 or older.

These PRR enrollee demographics are similar to the demographics of the Medicaid population at large.

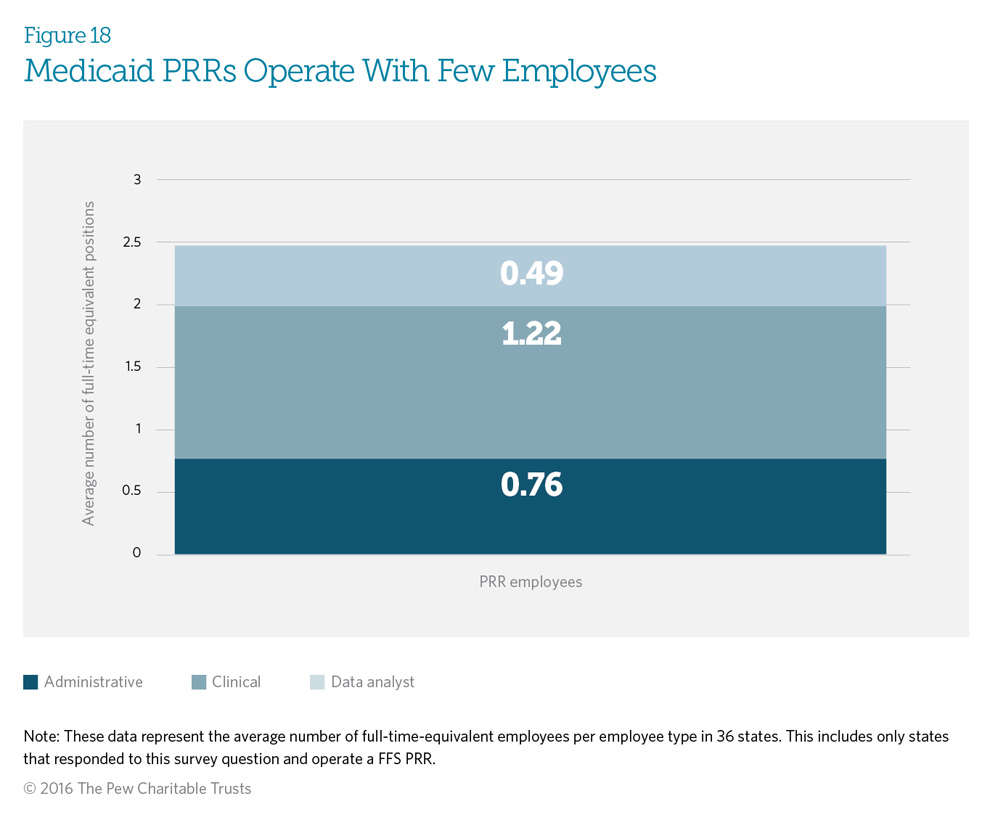

Medicaid fee-for-service programs operate patient review and restriction (PRR) programs with an average of 2.47 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff members to run the entire program, which includes administrative, clinical, and data analysis functions. Staff sizes range from 0.03 (or 3 percent of an FTE) to 10 FTE employees. Nine programs operate with less than one FTE. Clinicians represent the most common type of personnel used by Medicaid PRRs, with an average of 1.22 FTE clinical staff.

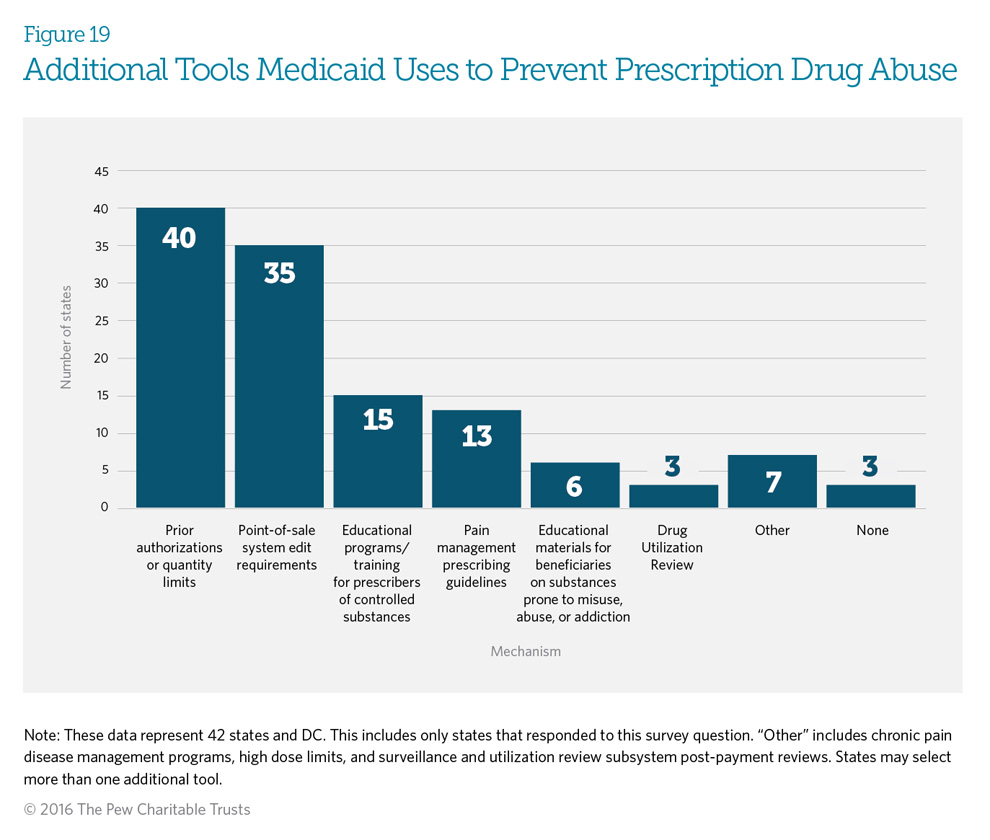

Ninety-three percent of responding states use several mechanisms other than, or in addition to, patient review and restriction (PRR) programs to prevent potential abuse of controlled substances. Eighty-one percent of states use point-of-sale edits in combination with either prior authorization or quantity limits to help prevent prescription drug abuse (see Glossary of Definitions for definitions of point-of-sale edits, prior authorization, and quantity limits). Thirty-five percent (15 programs) use educational programs and training for prescribers of controlled substances, and 30 percent (13 programs) offer pain management prescribing guidelines.

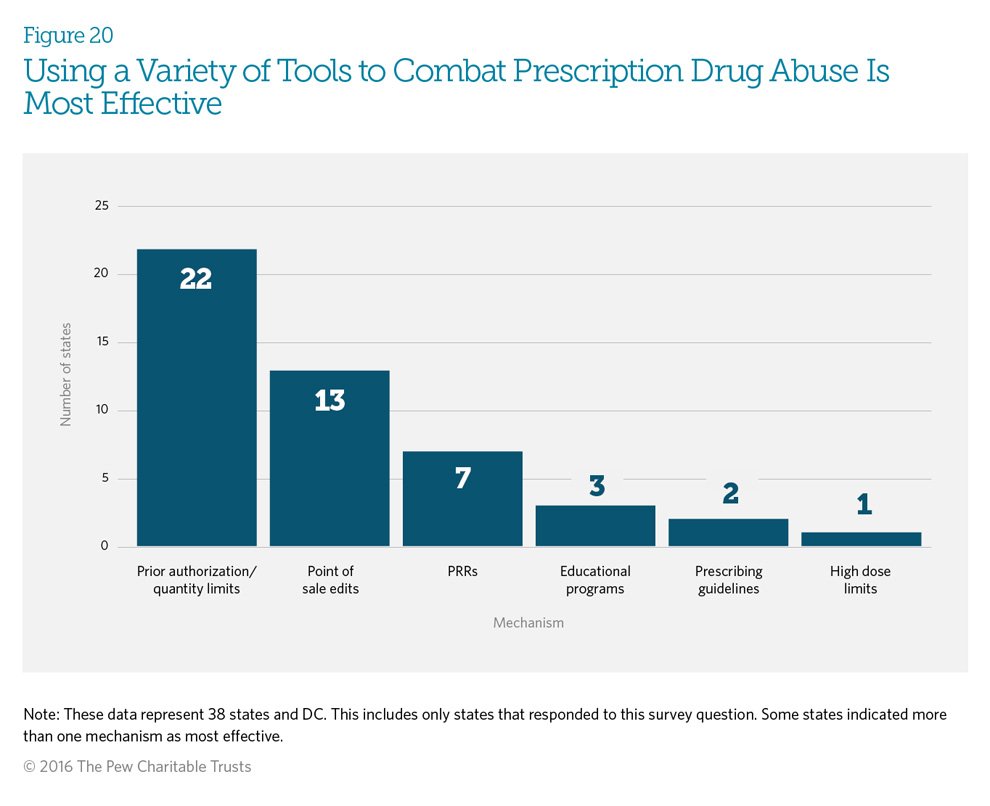

Fifty-nine percent (23) of the responding states indicated that a combination of mechanisms, including patient review and restriction (PRR) programs, is probably the best approach to reduce and prevent prescription drug abuse. Fifty-six percent (22) of states responding believe that prior authorization or quantity limits are the most effective mechanisms. Eighteen percent (7 states) find a combination of point-of-sale edits, prior authorization, or quantity limits to be most effective. (See Glossary of Definitions.) Seven states— Alaska, Indiana, Louisiana, New York, Nevada, South Carolina, and Wisconsin—find PRR programs to be the most effective.

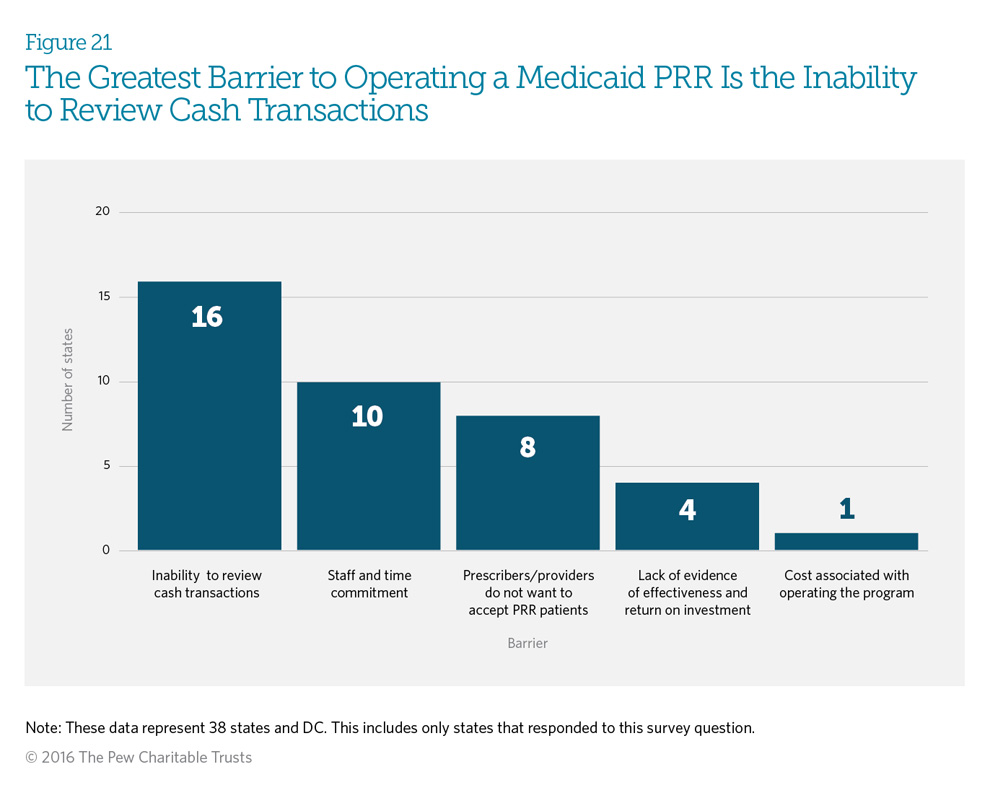

Forty-one percent (16) of responding states indicated that the inability to review cash transactions is the greatest barrier to operating a patient review and restriction (PRR) program, because if a provider or pharmacy does not submit a claim for reimbursement, the Medicaid department cannot identify the prescription or episode of care. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) allow insurers to identify cash payments, but 58 percent (22 programs) of Medicaid PRRs do not have access to the PDMP. (See Figure 14.) Twenty-six percent (10 programs) viewed staff and time commitments as the largest barrier. Four states—Hawaii, Indiana, Maryland, and Minnesota— responded that they do not have any current barriers, with two of the states attributing it to the small FFS populations that their PRRs serve.

Errata

Michigan clarified that its FFS PRR began in 1979, not 2014, as originally noted. Figure 2 was updated on April 6, 2016 to reflect this.

Endnotes

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2000–2014,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64, no. 50 (2016): 1378–82, http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm?s_cid=mm6450a3_w.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Patient Review & Restriction Programs: Lessons Learned From State Medicaid Programs” (2012), http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pdo_patient_review_meeting-a.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment and Program Characteristics, 2013 (2013), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/data-and-systems/medicaid-managed-care/downloads/2013-medicaid-managed-care-enrollment-report.pdf.

- National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws, “Types of Authorized Recipients—Medicaid, Medicaid, State Health Insurance Programs, and/or Health Care Payment/Benefit Provider or Insurer” (2015), http://www.namsdl.org/library/BD358168-D6AA-144F-EED55B39AF9E52B5/.

- Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, Part D Beneficiaries With Questionable Utilization Patterns for HIV Drugs (2014), http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-11-00170.pdf.

Patient Review and Restriction Programs Curb Opioid Misuse

Medicaid programs use PRRs to address inappropriate use of prescription drugs and reduce the risk of overdose