The United Kingdom’s Overseas Territories Harbour an Environment Worth Protecting

The government’s Blue Belt policy aims to preserve some of the world’s most outstanding wildlife

© The Pew Charitable Trusts

© The Pew Charitable TrustsThe United Kingdom, through its Overseas Territories, is home to more penguins than any other nation.

This article was updated July 8, 2016, to correct the number of species endemic to the United Kingdom Overseas Territories that the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed and listed as globally threatened, and March 24, 2016, to reflect updated messaging for Pew’s UK and overseas engagement.

In recent years, the British government has led the world in marine protection. The country’s leaders have committed to fully protecting the islands and coral reefs of the British Indian Ocean Territory, the pristine Pacific waters of the Pitcairn Islands, and the rich biodiversity around Ascension Island in the Atlantic Ocean.

The U.K. has not done this alone: Pew’s Global Ocean Legacy project has played a key role in each of Great Britain’s landmark commitments, with scientific research, community engagement, and development of the Eyes on the Seas platform, which leverages satellite technology to greatly advance monitoring of and law enforcement in large, remote marine reserves.

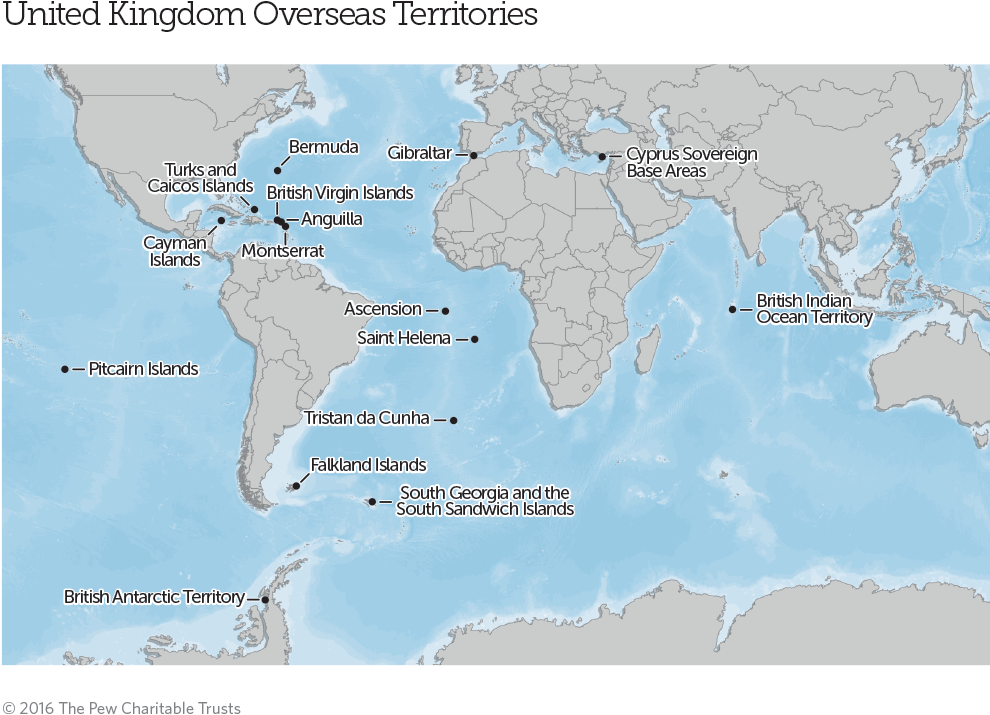

The human population of the 14 United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs) is approximately 250,000, or 0.004 percent of the population of the U.K. Yet these territories hold 90 percent of the United Kingdom’s biodiversity—including numerous range-restricted, low-population endemic species.

Unfortunately, they also face the considerable challenge of balancing a desire for environmental protection with a need for economic development, along with managing the logistics that come with geographic isolation. For example, the community of Tristan da Cunha, in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, is the most isolated island population in the world. The few dozen residents there want to safeguard their waters but also need to exploit the coastal environment for income. Further, they lack the monitoring and enforcement capacity to protect the seas surrounding their island from outside poaching.

The U.K. Government is attempting to address this problem through its Blue Belt policy, unveiled in May 2015. The pioneering conservation strategy aims to enhance protection of marine life in each of the UKOTs, through measures such as the designation of large, highly protected marine reserves.

In a new scientific paper,1 published in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation, a team of authors assessed the biodiversity of the UKOTs and found that the sites harbour over 32,000 native species, of which more than 1,500 are endemic—that is, found only in a specific place. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed 145 of those endemic species and found three-quarters of them—111 species—to be globally threatened.

The UKOT’s endemic species account for 16 times as many known endemic species as are found in the rest of the country. These endemics include a shrimp confined to two rock pools on Ascension Island, the Virgin Islands dwarf gecko—one of the world’s smallest land-living vertebrates—and the Tristan Thrush.

These findings show the need to protect the biodiversity of the U.K.’s Overseas Territories. Without comprehensive and well-enforced conservation measures, including the Blue Belt policy, these mainly isolated outcrops of globally important habitats will eventually face the same threats that have compromised so much of the global ocean.

The U.K. Government, as the custodian of such varied and unique natural environments, must continue its good work. The Blue Belt strategy could enhance marine conservation measures around territories as varied as Tristan da Cunha and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands for generations to come. That would be an ocean legacy of which we can all be proud.

Matt Rand directs Pew’s Global Ocean Legacy project. Johnny Briggs is a senior associate with Pew’s Global Ocean Legacy project in the United Kingdom.

Endnote

- Thomas Churchyard et al., “The Biodiversity of the United Kingdom’s Overseas Territories: A Stock Take of Species Occurrence and Assessment of Key Knowledge Gaps,” Biodiversity and Conservation (2016), doi:10.1007/s10531-016-1149-z.