Ocean Upwelling Becoming More Intense Along West Coast, Study Finds

As Bob Dylan wrote almost five decades ago, you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

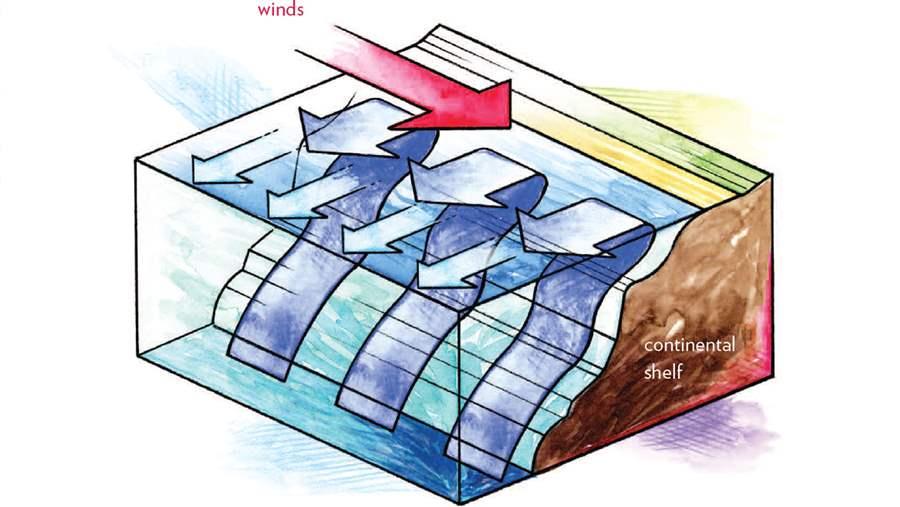

Those of us who live along the U.S. West Coast already know that we can expect strong and sustained winds from the northwest in the late spring and summer. We also know those winds create an ocean condition called upwelling, in which cold, nutrient-rich water is drawn to the surface from deep below the waves.

These conditions fuel the growth of tiny plants and animals, called plankton, which live near the surface and support massive schools of forage fish that, in turn, become a buffet for seabirds, seals, whales, and bigger fish such as tuna and sharks. All of this characterizes one of the most ecologically diverse ecosystems on Earth.

So more upwelling must be good, right?

Not necessarily. A new peer-reviewed study published this month in the journal Science documented intensifying winds over the past 60 years. This research suggests that increasing upwelling could exacerbate the effects of ocean acidification and raise the risk of hypoxia—or low-oxygen waters commonly known as dead zones.

In fact, excessive upwelling boosts ocean acidity in a way that directly threatens shell-forming creatures such as pteropods (free-swimming sea snails and slugs) and many more animals affected by low water-oxygen levels.

Upwelling occurs in the late spring and summer when wind drives cooler, dense, and nutrient-rich water toward the ocean surface, replacing the warmer surface water. High nutrient levels can fuel plankton growth. However, excessive upwelling can create problems.

The study’s lead author, Bill Sydeman, knows the Pacific ecosystem as well as anyone. As he told the Los Angeles Times in an article published July 3, intensifying wind could be good if it brings a surge of plankton, forage fish, and other species. “On the other hand,” he said, “it could be really bad” if it raises turbulence, disrupts feeding, worsens ocean acidification, and lowers oxygen levels.

In light of these and other changes, it’s worth noting that the Pacific Fishery Management Council adopted its first fishery ecosystem plan a year ago. This plan provides a framework for fishery managers to consider how everything is connected in the ocean, ascertain early warning signs of trouble brewing, and manage fisheries in such a way as to build resilience in an ecosystem under stress.

Over the next few months, fishery managers have a chance to put in place some sensible measures to promote ecosystem health. For example, if the impacts of increased upwelling are having a negative impact on the food source of forage fish, then strengthened protections for these fish may be warranted.

The council deserves credit for committing in April to move ahead with the ecosystem plan’s first initiative: protecting forage species such as sand lance and saury that aren’t yet being fished on the West Coast. This year, the council will consider new protections of crucial seafloor habitat, such as deep-sea corals and sponges, for groundfish species that are slowly recovering from decades of overfishing.

Both of these measures are great examples of using an ecosystem-based approach to manage fisheries in a rapidly changing environment.

It may not take a weatherman to know which way the wind is blowing, but it does take scientists to recognize that the wind is growing more intense. And it takes committed fishery managers to use that data and protect ecosystems in the face of new challenges.

Paul Shively manages ocean conservation efforts along the West Coast for The Pew Charitable Trusts.