Employment Rate Lags in Most States

These data have been updated. To see the most recent data and analysis, visit Fiscal 50.

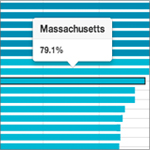

Employment rates for 25- to 54-year-olds were lower in 35 states in fiscal 2013 than in 2007, before the Great Recession. This decline means less revenue for state governments from personal and business income taxes and sales tax—and often increased strain on assistance programs.

In 2007, leading up to the Great Recession, nearly 80 of every 100 people ages 25 to 54 years old in the United States had a job. In the 12 months ending June 2013, well after the recession ended, only about 76 of every 100 people in that age group were working.

Download the data

This 4 percentage point decline in the employment to population ratio for people in their prime working years shows that the U.S. labor market remains weak. This finding has significant budgetary consequences for states:

- Without paychecks, people pay less income tax and tend to buy less, reducing sales and business income tax revenue.

- Unemployed people frequently need more services, such as Medicaid and other safety net programs, increasing costs at a time when state governments have less tax revenue.

Where Employment Rates Lag the Most |

|||

| For every 100 prime-age workers, how many fewer had a job in FY 2013 than in 2007? | |||

| Nevada | 8.3 | ||

| New Mexico | 8.1 | ||

| Florida | 6.3 | ||

| Arizona | 6.0 | ||

| Montana | 5.8 | ||

| Source: Pew analysis of data from the Current Population Survey, published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau | |||

A state-by-state comparison of calendar 2007 to the fiscal year ending June 2013 shows:

- No state reported employment rate gains for 25- to 54-year-olds.

- Thirty-five states had statistically significant decreases.

- The largest decline in the employment rate was in Nevada, where 73.8 percent of prime-age workers had jobs in fiscal 2013—8.3 percentage points lower than in 2007.

- Among the least affected were Nebraska and Vermont, which saw the smallest observable changes from their current employment rates of 84.9 and 82.6 percent, respectively.

While unemployment figures receive more media attention, the employment rate is a preferred index for many economists because it provides a sharper picture of changes in the labor market. The unemployment rate, for example, fails to count workers who stopped looking for a job. By focusing on 25- to 54-year-olds, trends are less distorted by demographic effects such as older and younger workers’ choices regarding retirement or full-time education.

A statistically significant decrease indicates a high level of confidence that there was a true change in the employment rate. Changes that are not statistically significant offer less certainty and could be the result of variations in sampling and other methods used to produce employment estimates. Without additional testing for statistical significance, caution should be exercised when comparing change in one state’s employment rate to change in another state’s rate.

Analysis by Jeff Chapman and Julie Srey