The Magnificent Owyhee Canyonlands

By Matt Skroch

Click to enlarge |

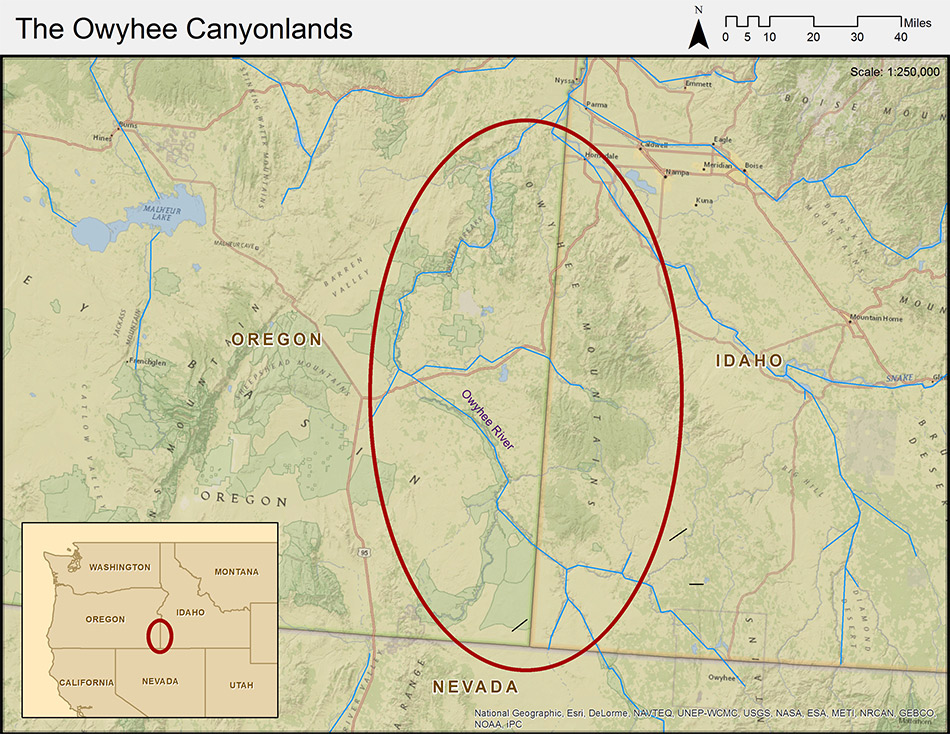

It's 4 in the morning and the wind is howling at gale force, crushing the tent against my body and threatening to blow us straight off the canyon rim in one of North America's most remote wild lands. Created by the Owyhee River, this canyon wilderness in southeastern Oregon is one of the largest unprotected roadless areas in the Lower 48 states. Unable to sleep, I crawl out into the dark and am hit by blasts of dirt as I disassemble my tent and seek refuge in the driver's seat of a mud-covered four-wheel-drive truck. Finally, sleep.

Three hours later, our crew of four crawls out of vehicles and tents to take stock. It's drizzling, and the wind continues to roar as we peer into the canyon that is our destination. There is no trail here, nor anywhere along the planned three-day route among the canyons in Oregon's portion of the mighty Owyhee wild-land complex. The four of us—a group of photographers, hiking guides, and conservationists interested in protecting the Owyhee—huddle with Chris Hansen, our trip leader and Owyhee wilderness coordinator for the Oregon Natural Desert Association. After figuring out which caves we can use for shelter if the weather worsens, we decide to proceed.

Just getting to the edge of the Owyhee is difficult, and now we are going in deeper. We are three hours off the nearest pavement, having navigated the mud tracks that are the closest we will come to a road. Our welcome party is a herd of dainty pronghorn, loping through the sagebrush with ease, as if daring us to a race. Goodbye, civilization; hello, wildness.

It didn't take long to realize that, despite its obscurity, the Owyhee can hold its own against any of our nation's vast wild lands.

Because of its remoteness, this place has largely avoided the attention attracted by other major wild-land complexes, such as southern Utah's slickrock country, Arizona's “sky islands,” and California's Sierra Nevada. Also, despite its stunning canyons, rivers, and mountains, Oregon's Owyhee country has no national park, no national conservation area—not even a single acre of designated wilderness, despite its perfect eligibility.

Chris and his organization, partners of Pew's U.S. public lands initiative, are working to change that. As mostly public land overseen by the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, vast swaths of Owyhee country have been classified as wilderness-quality, some parts for decades as interim “wilderness study areas” and others more recently acknowledged for their wilderness characteristics but with no formal protection. Regardless of current classification, the conservation goal for the Owyhee is clear: long-term protection of the habitat, its scenic value, and the primitive recreational opportunities it provides.

The opportunity for protecting the Owyhee has two components. First, the BLM is to release a draft of the new management plan for this area next year, outlining what parts it will manage for conservation or other uses, such as wind energy development. Open to public comment and likely to change on its way to finalization, the plan is a key element for the protection of the Owyhee's lands. Over the last several years, Pew has worked with the Oregon Natural Desert Association to undertake a comprehensive inventory of wilderness lands—data that were instrumental in the BLM's recent decision to acknowledge that more than 1.1 million acres contain wilderness characteristics, in addition to previously designated wilderness study areas. The second track is congressional designation of the Owyhee as wilderness, which would place the best of this region in the National Wilderness Preservation System. This longer-term goal requires strong support from Oregonians and their elected leaders, a goal that Pew and the Oregon Natural Desert Association are carefully working to facilitate.

Back in the canyon after our descent from the rim, the wind has calmed and the rain comes and goes, giving us enough respite to enjoy the incredible scenery. Cliff swallows flit above us, and the occasional rattlesnake slithers by as we make our way down Antelope Canyon toward the main stem of the Owyhee River. That evening, Chris points to a cave where I can spend the night. After inspection, I like the idea and arrange my bedroll inside for a great night's sleep. Two days later, after exploring the nooks and crannies of this spectacular place, we find a side canyon back to the rim and bid farewell to the Owyhee Canyonlands, for now. Amazingly, a mountain lion appears on our way out and briefly stares at us before loping into the brush. As I reflect on this trip, I smile with appreciation that landscapes like the Owyhee still exist—a place that deserves to endure far into the future as part of America's great wilderness heritage.