From Volatile Severance Taxes to Sustained Revenue

Key recommendations to improve state sovereign wealth funds

Governments use sovereign wealth funds to deposit a portion of revenue in an investment account intended to generate returns that will be used to achieve a specific public purpose or set of goals.

© Getty Images

Overview

In 2014, collections from West Virginia’s taxes on natural resource extraction—called severance taxes—reached a historic peak, more than doubling to $680 million from about $300 million in 2005, according to U.S. census data. A sizable portion of the state’s revenue was already attributable to mineral extraction from decades of coal mining. But starting in the early 2000s, advances in the technologies for horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, often referred to as fracking, sparked an energy boom that helped drive production of natural gas to record levels and left many U.S. states flush with cash. Recognizing the promise of this thriving new revenue, state lawmakers established a severance tax-based sovereign wealth fund, known as the West Virginia Future Fund, so that the current resource wealth could benefit future generations.

Governments use sovereign wealth funds, so-called because they are established by a sovereign nation or U.S. state, to deposit a portion of revenue in an investment account intended to generate returns that will be used to achieve a specific public purpose or set of goals. In a May 2016 interview with The Pew Charitable Trusts, the West Virginia fund’s legislative sponsor, state Senator Jeff Kessler, said, “With the horizontal drilling and the Marcellus Shale finds [a geological formation rich in natural gas deposits], I saw a huge opportunity to let market forces work for us. We had something that people were coming into our state for.”

When severance tax collections are strong, it can be tempting for lawmakers to see them as a funding source for ongoing spending commitments. As Sen. Kessler explained, “Once politicians get used to seeing money and spending it, it’s hard to get them to not become dependent on it.” And a heavy or growing reliance on highly volatile severance tax collections can pose a serious threat to the long-term structural balance of a state’s budget. When revenue is high, so is the temptation to spend it. When collections are low, lawmakers who’ve come to depend on those severance taxes to pay for operating expenses are left scrambling to fund the state’s recurring expenditures. However, by depositing above-trend revenue from volatile severance tax collections in a reserve fund for future uses, such as a sovereign wealth fund, states can solve some of these challenges.

Yet another concern stems from the fact that severance taxes are rooted in the removal of finite natural resources, meaning that beyond the normal price fluctuations of a volatile market, revenue will eventually decline as the resources are exhausted. Failure to invest resource wealth represents an enormous missed opportunity, a lesson that many states have learned either from the current drop in energy prices or from past experiences. According to a study by the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, had the state set aside a 1 percent severance tax on coal starting in 1980, it would have accumulated nearly $2 billion by 2010—even if two-thirds of the fund’s annual investment returns had been used to support the state’s operating budget. To place that amount in context, total fiscal year 2010 appropriations for West Virginia were approximately $9.1 billion, inclusive of both state and federal funds, according to the state budget office.

To help policymakers better understand the challenges and opportunities afforded to them by sovereign wealth funds, Pew examined the constitutional and statutory language pertaining to the establishment and operation of these funds in U.S. states. In addition, Pew conducted interviews with the policymakers responsible for establishing recently created funds in the United States.

In brief, the research showed that:

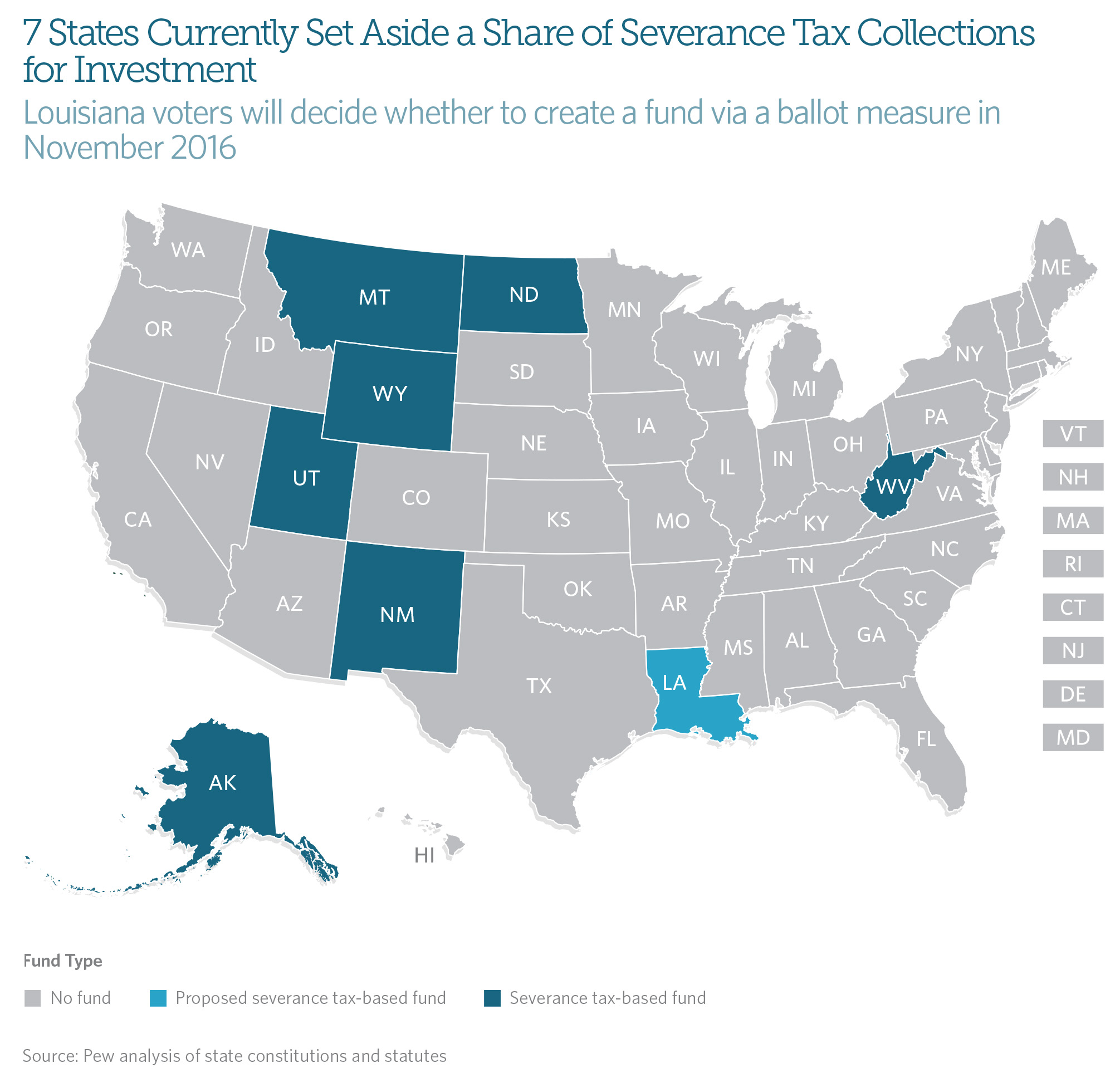

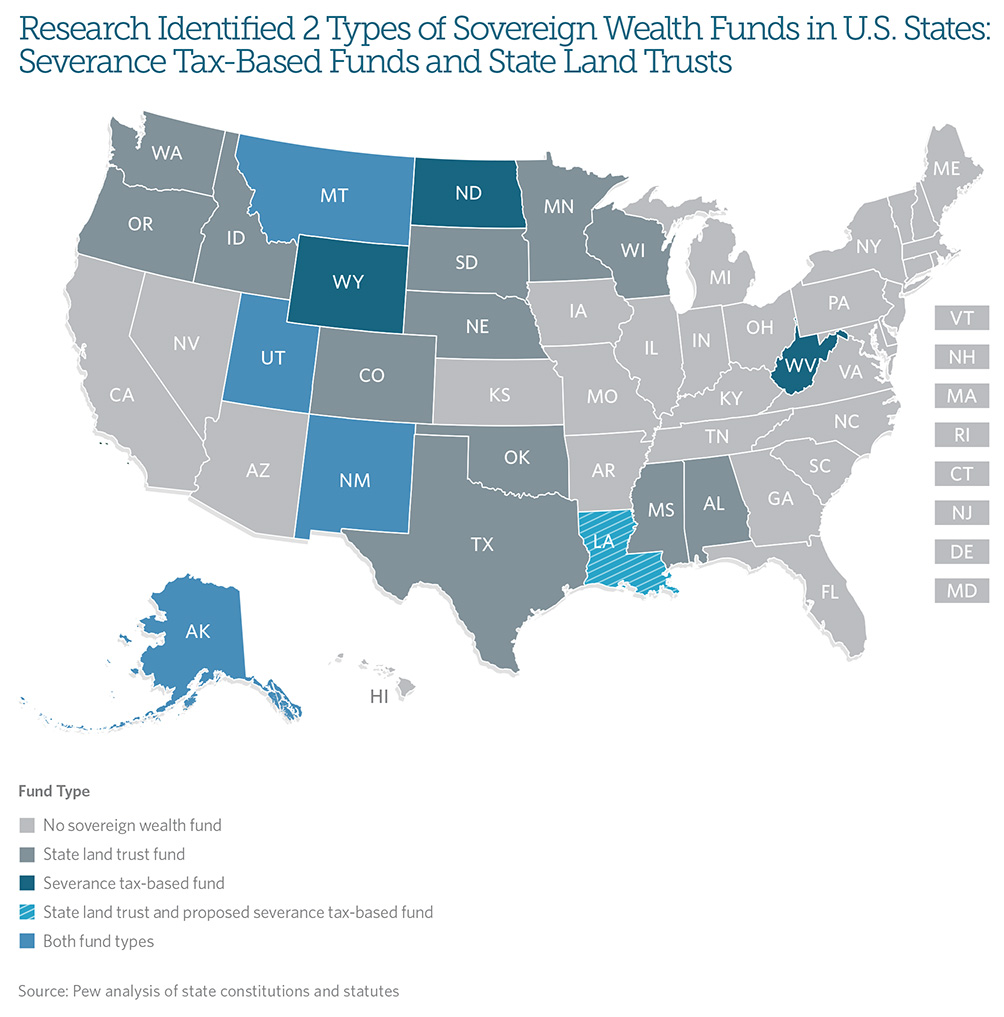

- Only seven U.S. states operate severance tax-based sovereign wealth funds. Among those states, only two— Alaska and West Virginia—have well-defined purposes for the funds written into state law. In Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming, the use of interest accruals and investment earnings, as well as the long-term objectives of the funds, is unclear.

- Alaska, West Virginia, and Wyoming are the only states that do not allow withdrawals from the principal. While the option for lawmakers to withdraw from these funds provides a state with increased fiscal flexibility in times of need, withdrawals can severely impede a fund’s ability to fulfill long-term objectives.

- Most funds direct interest accruals and investment earnings toward their states’ general operating funds. One strength of sovereign wealth funds is their ability, through investment holdings, to generate additional revenue that can increase their principal—or be used to cover general fund expenditures—without any additional deposits.

Pew’s analysis of census data found that nine states drew more than 5 percent of their total revenue from severance taxes from 1995 to 2014. In six of those states—Louisiana, Montana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming—severance taxes were the most volatile major tax source. In the remaining three states—Alaska, New Mexico, and West Virginia—severance taxes were the second most volatile major tax source. For each of these states it is especially important for lawmakers to consider the volatility that comes from commodity prices.

A severance tax-based sovereign wealth fund is one tool policymakers could consider to answer the challenges posed from a high reliance on these taxes, as it can help transform this volatile, finite tax stream into more permanent, revenue-generating assets. This type of long-term savings fund provides opportunities for U.S. states that collect this type of revenue to generate long-run investment earnings while managing the volatility of the revenue flowing to the general fund. In order to best transform finite severance tax collections into sustained revenue, Pew recommends that U.S. state policymakers:

- Identify the purpose of their state’s sovereign wealth fund and clearly articulate its goals in law. It is difficult to determine how much to save and how to best utilize funds when the purpose is not explicitly stated or clearly defined.

- Establish policies for the governance, investment, and public disclosure of the fund’s activities in law. Because sovereign wealth funds invest public funds into private markets, both domestic and international best practices emphasize the importance of clear legal guidance and transparency.

- Provide statutory or constitutional guidance regarding withdrawals from the principal. In order for a sovereign wealth fund to build a large interest-generating balance, the principal must remain intact. While withdrawals can help address a state’s short-term needs, they diminish the fund’s ability to generate investment revenue.

- Be aware of volatility in interest earnings from the fund. Sovereign wealth funds have the potential to generate significant amounts of interest and investment earnings. Most U.S. states with these funds have directed them, in whole or in part, toward their general fund budgets. However, the volatility of this revenue is linked to the fund’s investment strategy and the fluctuations of the financial markets.