Pacific Sardines: Critical Food Source in Steep Decline

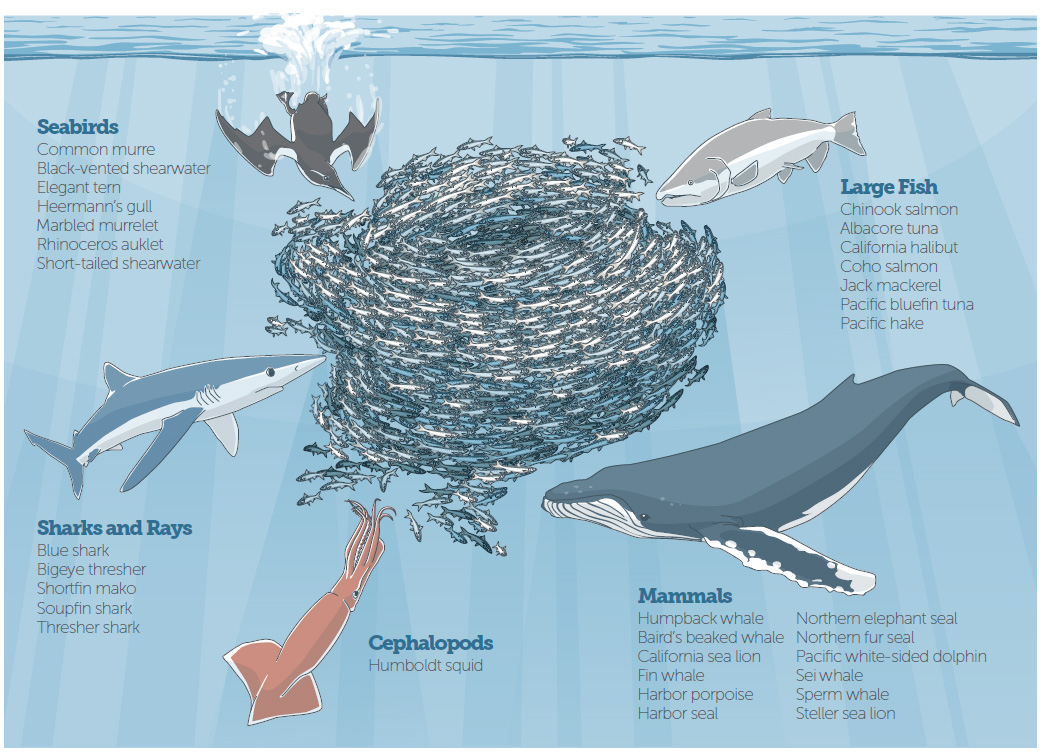

The Pacific coast of North America supports one of the most vibrant and diverse marine ecosystems on Earth, largely because of the presence of thick schools of small prey fish such as Pacific sardines. Unfortunately, this crucial forage fish appears to be in the midst of a severe population decline. Its absence will be felt by dozens of species of West Coast seabirds, whales, sharks, dolphins, and commercially important fish such as salmon and tuna that depend on sardines as a major food source. In addition, because sardines have been a staple of commercial purse-seine fishing on the West Coast, their decline raises the potential for fishing pressure to shift to similar, but more abundant, schooling species of forage fish.

The Pacific Fishery Management Council, which manages fishing in federal waters off California, Oregon, and Washington, should do two things to help maintain a healthy Pacific Ocean:

- Set conservative catch limits on sardines when the population is so low.

- Fulfill its September 2013 commitment to prohibit unregulated fishing on forage fish species such as sand lance, saury, and lanternfish that are not currently managed or monitored.

Cause for concern

Populations of forage fish along the West Coast fluctuate widely, so a species can be abundant one year and dwindle unexpectedly the next. That's because forage fish are highly dependent on the upwelling of cold nutrient- rich waters to stimulate the growth of phytoplankton, their primary food source.

The Pacific sardine fishery, immortalized in John Steinbeck's novel Cannery Row, collapsed notoriously the 1950s. The November 2013 population estimate of 378,000 tons is the lowest in more than a decade, far below the peak of 1.5 million tons estimated in 2000 and a major decline by historical standards. Geological records of fish scales deposited off Southern California indicate that the unfished sardine population fluctuated naturally between a low of 400,000 tons to as much as 16 million tons.

Keeping an eye on the big picture

Forage fish account for more than one-third of the global catch of marine fish and are mostly used for industrial purposes such as feed for livestock, poultry, and farmed fish rather than being directly eaten by people. Most forage fish landed on the West Coast are exported for purposes such as bait in tuna longlining in Asia or as feed for farmed fish. In 2012, the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force, a group of eminent scientists from around the world, calculated that forage fish worldwide are worth twice as much when left in the water—about $11.3 billion—as they are when caught because of their value as food for commercially important predators.

For further information, please visit: pewenvironment.org/pacificfish

Write the Pacific Fishery Management Council at: [email protected]