Prince William Forest Park

Virginia

Pew created this case study using National Park Service deferred maintenance data issued in fiscal year 2015. The information listed here may no longer reflect the NPS site’s current condition or maintenance requirements. To find the most up-to-date information, please use the National Park Repair Needs tool.

Overview

Each year, thousands of families, school groups, and youth program participants visit Virginia’s Prince William Forest Park to hike, bike, camp, or otherwise explore the area. Just 35 miles outside Washington, the 15,000-acre park protects part of the Quantico Creek watershed and the largest swath of Piedmont forest in the National Park System.

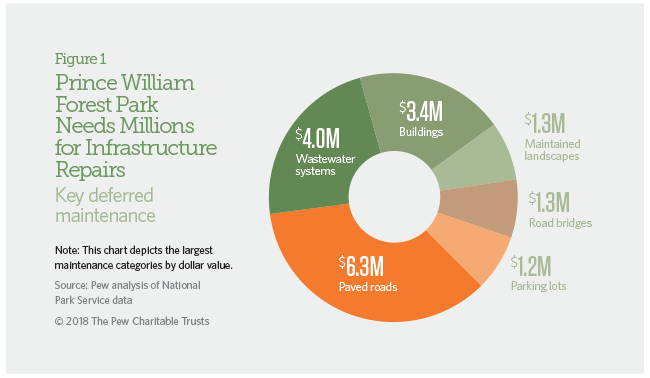

Congress designated the park during the Great Depression as a retreat where urban youth could be immersed in nature. In the 1930s, the park, then called Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area, welcomed thousands of children from the capital, who slept in cabins built by the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration. In 1948, the site was renamed Prince William Forest Park. Groups such as NatureBridge and Bridging the Watershed continue this legacy by bringing children and teens from Washington and surrounding counties for daytime and overnight environmental education programs. Unfortunately, the park now faces $19.8 million in deferred maintenance because of deteriorating infrastructure, increasing visitation, and insufficient federal funding.

Prince William Forest Park’s $19.8 million in deferred maintenance includes many historic cabins and bath houses.

© The Pew Charitable TrustsMaintenance challenges

Ongoing maintenance needs include replacing building roofs and outdated sewage infrastructure and repaving roadways. When the park is not able to complete these tasks at required intervals, they are added to its maintenance backlog.

Staff members are responsible for maintaining 170 historic cabins and more than 100 other structures. To reduce repair costs, Prince William Forest Park has begun replacing the deteriorating asphalt shingles on cabin roofs with composite shingles. They look similar to the original wood shake roofs, cost the same or less, and have a 50- to 70-year life span.

The park also is repairing and replacing the original clay sewage pipes that service campsites, which are vulnerable to damage from tree roots. Plumbing backups have caused restrooms to be closed for repairs.

Several historic bridges at the park also need maintenance. The park is working with contractors to repair the Pyrite Mine Bridge, its oldest. The historic truss supports and an abutment need to be fixed to ensure that the bridge can support small vehicles. Although this project is expected to be funded soon, other bridges in the park need nearly $1 million for repairs.

Other items on Prince William Forest Park’s backlog include roadways, with a price tag of $6.3 million, and a constructed lake and dam network, which requires more than $1.5 million in repairs. Addressing the park’s deferred maintenance needs will ensure that it continues to serve as a recreational asset and outdoor classroom for current and future generations.

Everybody should have the experience of learning through the lens of a nature adventure. Students were engaged in productive talk, experimenting, and curiosity. It's amazing how much learning takes place when students are immersed in the actual environment. Computers, pictures, and virtual learning rooms can't replicate this experience. It is awesome!5th grade teacher, Washington, D.C., NatureBridge participant

Recommendations

To address the infrastructure needs at Prince William Forest Park and other National Park Service (NPS) sites in Virginia and across the country, Congress should:

- Ensure that infrastructure initiatives include provisions to address park maintenance.

- Provide dedicated annual federal funding for national park repairs.

- Enact innovative policy reforms to ensure that deferred maintenance does not escalate.

- Provide more highway funding for NPS maintenance needs.

- Create more opportunities for public-private collaboration and donations to help restore park infrastructure.

Prince William Forest Park Facts

2016

| Visitor spending | $19.8 million |

| Jobs created by visitor spending | 259 |

| Economic output | $25.9 million |

| Labor income | $10.3 million |

| Visits | 344,435 |

| Deferred maintenance (fiscal year 2015) | $19.8 million |

Sources: National Park Service, “Visitor Spending Effects,” accessed Oct. 6, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/socialscience/vse.htm; National Park Service, “NPS Deferred Maintenance Reports,” accessed Oct. 6, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm.

© 2018 The Pew Charitable Trusts

The Pew Charitable Trusts works alongside the National Parks Conservation Association, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and other national and local groups to ensure that our national park resources are maintained and protected for future generations to enjoy.