Finding the Missing Fish

What reconstructing fish catch can teach us about the world’s oceans

© The Pew Charitable Trusts

© The Pew Charitable TrustsIndustrial fishing is big business. Official global statistics show that commercial operations take approximately 80 million metric tons of fish from the oceans each year. However, as scientists uncover the extent of small-scale fishing—which often goes unreported—this amount may actually be much larger.

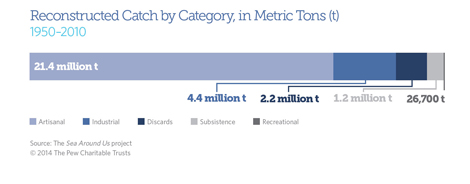

Fisheries scientists have long recognized the important role played by comprehensive catch data in understanding the pressures on target species. Most countries, however, focus their data collection efforts on industrial fishing, in part because small-scale operations can be difficult to track. The resulting data largely exclude smaller types of catch such as artisanal, subsistence, and illegal fishing, as well as discards, masking the true extent of fishing worldwide.

One promising approach to better capturing the scale of fishing around the world is “catch reconstruction,” which offers estimates using an array of sources and methods. Sea Around Us, a partnership between The Pew Charitable Trusts and the University of British Columbia, developed the concept.

“It’s like putting together a 500-piece puzzle to get a more complete picture of a fishery’s catch data,” said Daniel Pauly, principal investigator for Sea Around Us and professor at the University of British Columbia. “Over time, the estimates reveal themselves, and you have data where once there were none.”

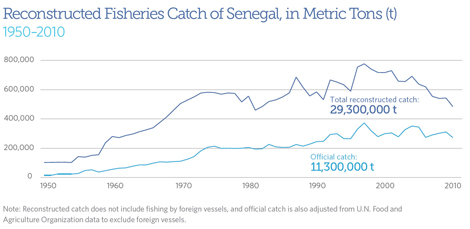

Official vs. Reconstructed Catch

Click the figure to expand.

These estimates are not a substitute for the data that countries report to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Rather, they are a supplement that can highlight important trends and provide guidance on how best to improve data collection.

The danger in underreporting fish catch is that country officials don’t have the data they need to implement effective fisheries management measures, such as science-based quotas.

“It’s like managing your bank account,” said Pauly. “You have to know how much you have left before you can withdraw more. In some developing countries, the actual total catch can be 200 percent higher than what is being reported.”

In Senegal, on the west coast of Africa, small-scale fishing accounts for most of the domestic catch. Focusing on industrial fishing paints an incomplete picture. For example, the official data reported to the FAO indicate that the catch has held steady since about 1995, but reconstructed data suggest it is decreasing.

After the reconstruction was completed, Senegal government officials met with scientists from Sea Around Us to discuss ways to update their reporting and capture data they did not have access to in the past. With a clearer picture of their fisheries activities, officials may be able to improve management, for example by excluding foreign fishing vessels that might be affecting artisanal fisheries.

Click the figure to expand.

Sea Around Us will complete a global catch reconstruction this year, with estimates from 1950 to 2010, broken down by year and type of fish, for more than 250 countries and territories. To see some of these findings, click on a country or territory below to view catch construction data.

For the complete Dec. 15, 2014, videotaped interview of Daniel Pauly and more information about catch reconstruction, visit “The Sea Around Us Taking Stock of Our Fish Oceans and People.”