Building State Rainy Day Funds

Policies to Harness Revenue Volatility, Stabilize Budgets, and Strengthen Reserves

QUICK SUMMARY

This report will help policymakers prepare for the next economic downturn by explaining the ways states can design their rainy day funds to harness fluctuations in revenue. The Pew Charitable Trusts reviews the rules that guide when, how, and how much states are saving—including deposit rules and fund caps—and compares these policies with each state’s experience with volatility to identify best practices. This report is the second in a series that provides policymakers with strategies to improve long-term fiscal health and manage budget uncertainty, building on “Managing Uncertainty: How State Budgeting Can Smooth Revenue Volatility,” which examined patterns of revenue and economic volatility across the 50 states.

OVERVIEW

Over the past several decades, rainy day funds—formally known as budget stabilization funds—have been key to helping states manage ups and downs in revenue, but some are more effective than others. In many cases, balances have been inadequate to significantly offset revenue declines during recessions. For example, the 50 states collectively had about $60 billion set aside in summer 2008,1 but they faced a combined shortfall of nearly twice that—$117 billion—the following year.2 The Great Recession is an extreme example, but many rainy day funds were also insufficient during previous recessions. States could have set aside more in recent periods of growth if not for statutory limits on the total size of reserves and rules for deposits that make saving a low budget priority.

To help state policymakers craft effective policies and lessen the need for the most difficult budget choices, Pew researchers examined the mechanisms for depositing money into budget stabilization funds and compared these rules to tax volatility patterns and drivers in all 50 states. Researchers adjusted U.S. Census Bureau data to remove the effect of tax policy changes from 1994 to 2012, which helps to identify the underlying cyclical volatility in these tax sources. The research found that:

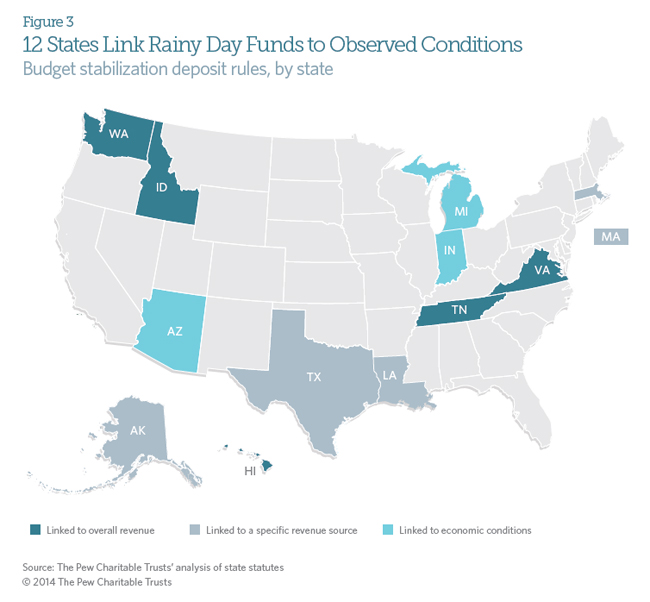

- Only 12 states connect the rules for when, how, and how much to deposit into their budget stabilization funds with underlying revenue or economic fluctuation.

- In many instances, caps on the size of the funds have prevented states from saving enough to substantially offset revenue losses.

Endnotes

1 The Pew Charitable Trusts, Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis (2014), http://www.pewtrusts.org/fiscal50.

2 National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Budget Update: November 2010” (December 7, 2010): 8, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/fiscal/november2010sbu_free.pdf.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Pew’s research identified three promising practices that can help state policymakers design budget stabilization funds that respond to economic and revenue volatility in order to deliver reliable savings in times of growth:

- Require regular studies to identify major sources of volatility and present appropriate policy solutions. These studies should determine which areas of the tax system are volatile, recommend ways to align budget stabilization fund policies with that volatility, and be revisited on a recurring basis.

- Tie budget stabilization fund deposits to observed volatility. To ensure that policymakers set aside a portion of one-time or temporary revenue growth, rainy day fund deposits should be tied to extraordinary or unexpected revenue increases. This can allow states to save more in high-growth years, when funds are available, and to set aside less in leaner years. Because each state’s economic and fiscal characteristics are unique, the ideal rule will vary from state to state.

- Set fund size targets that match the state’s experience with volatility. The amount of money states need to have on hand for downturns depends on their susceptibility to sudden swings. Even when deposits are linked to volatility, if the fund’s cap is too low, it can hinder creation of an adequate financial cushion.