It Pays to Prepare for Natural Disasters

Research points to the benefits of smarter decisions to reduce flood risk

Overview

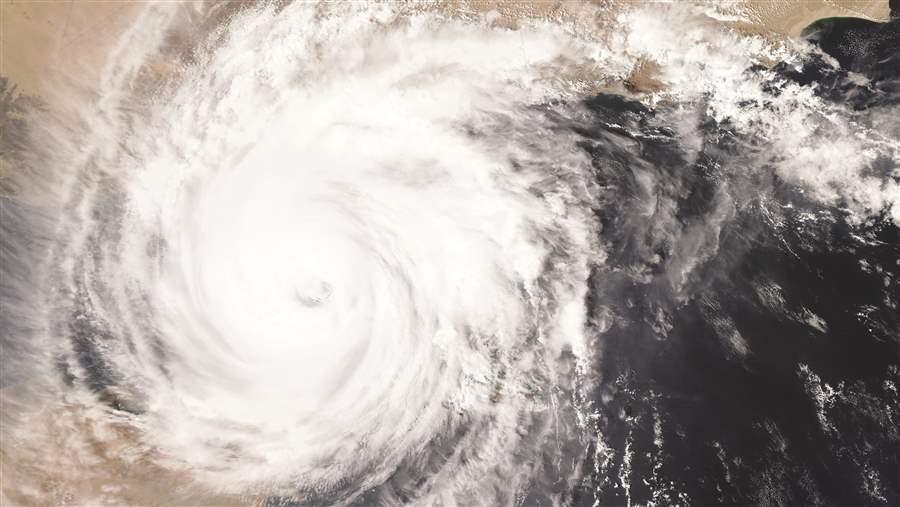

Billion-dollar natural disasters are becoming more common in the United States. Since 1980, catastrophes of this magnitude have affected all 50 states, hitting five to 10 times annually.1 Preventive actions to reduce the costly cycle of rebuilding and repair are needed now more than ever. There are steps that individuals, communities, and the federal government can take now to better prepare for and avoid the worst effects of extreme weather—and reduce costs.

With Hurricane Preparedness Week kicking off on May 7, here is a snapshot of the benefits of investing in flood preparedness.

Investing in preparedness saves taxpayers money

Research by an independent group of experts in 2005 found that for every dollar invested in actions to reduce disaster losses, the nation saves about $4 in future costs.2 For example, in 2011, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) mitigation programs helped communities across the United States prepare for floods by providing up to $252 million in grants for more than 1,300 properties. FEMA expected these measures would stave off about $502 million in potential losses for flood programs.3

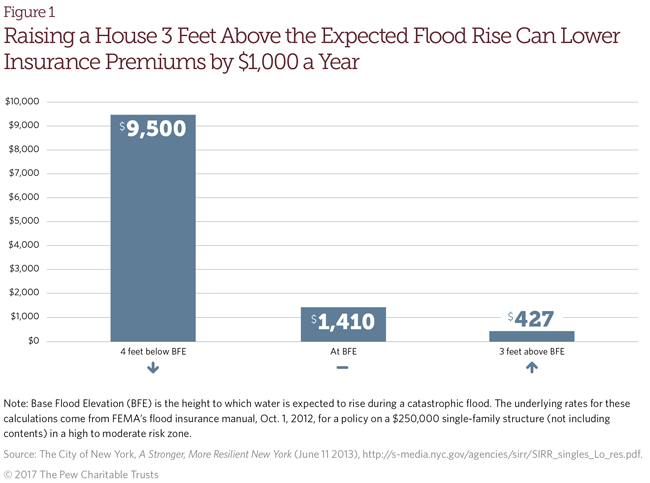

Homeowners can take action to reduce insurance costs

Property owners in high-risk areas can see significant drops in their flood insurance premiums when homes or utilities are elevated, or flood openings such as vents are installed in the lowest level of the house to reduce water pressure on walls. Some states and localities offer additional incentives for property protection, including grants and tax incentives.

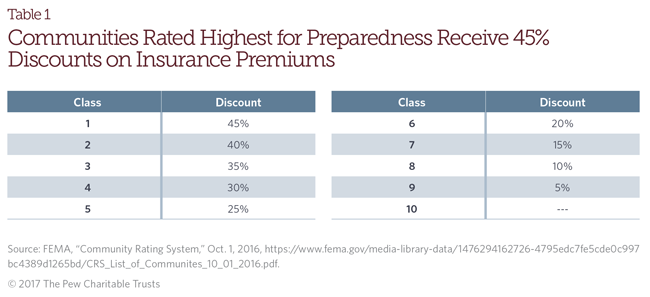

Communities benefit from taking proactive measures

Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) can sign up for a program called the Community Rating System (CRS). Under the CRS, communities that exceed the NFIP’s minimum standards earn reduced flood insurance premiums for all property owners in the community. FEMA scores enrolled communities on their floodplain management, considering factors such as open space preservation, stormwater management, and levee safety. Through CRS, communities focus on helping properties that already have more than one insurance claim from flood damage. When a community gets a CRS rating of 1, the highest possible score, property owners see a 45 percent discount on NFIP premiums. Unfortunately, the program’s participation rate is low; only about 5 percent of communities enrolled in the NFIP join it.4

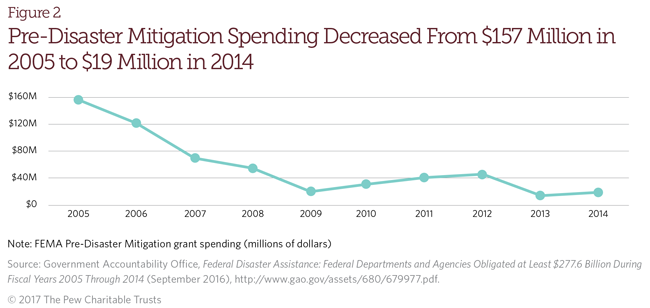

While the payoff is clear, the federal government has historically underinvested in risk reduction

Of the $277.6 billion that the federal government obligated on disaster assistance from 2005 to 2014, very little went to reducing communities’ risks before hurricanes and floods hit. Spending on FEMA’s Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant program, the federal government’s main vehicle to help states and local communities take actions to cut their risk of damage from major storms, dropped from $157 million in 2005 to $19 million in 2014.

Endnotes

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Time Series,” accessed May 2, 2017, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/time-series.

- National Institute of Building Sciences, Multihazard Mitigation Council, Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: An Independent Study to Assess Future Savings From Mitigation Activities (2005), http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.nibs.org/resource/resmgr/MMC/hms_vol2_ch1-7.pdf?hhSearchTerms=Natural+and+hazard+and+mitigation.

- Testimony of David Miller, associate administrator of the Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration, FEMA, before House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, July 24, 2012, https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1854-25045-5369/7_24_12___review_of_building_codes_and_mitigation_efforts.txt.

- FEMA, Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration, “Community Rating System Fact Sheet,” May 2016, https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1469718823202-3519e082e89a8c780670bb03f167bbae/NFIP_CRS_Fact_Sheet_May_03_2016.pdf.