'Give It a Go!’ With Help, Outback Rangelands Can Recover

The Outback—the cathedral of Australia—is crumbling. So says pastoralist Michael Clinch, a veteran stockman whose family has been living and working on the land for four generations. A century of neglect has left much of the Outback, which covers more than 70 percent of the continent, wilting under stresses that include invasive species and wildfires.

Hope for the area’s recovery lies in the work of Clinch and others like him, but the efforts won’t succeed on a broad scale without outside help, he says.

“We’re passionate about the Outback, and we want to share that passion and take anyone that’s willing on that journey of rangeland recovery—the Outback recovery, the grass recovery,” Clinch declares in The Pew Charitable Trusts’ study My Country, Our Outback: Voices From the Land on Hope and Change in Australia’s Heartland. It is the second in a series of peer-reviewed studies produced by Pew on conservation priorities and challenges across this vast region.

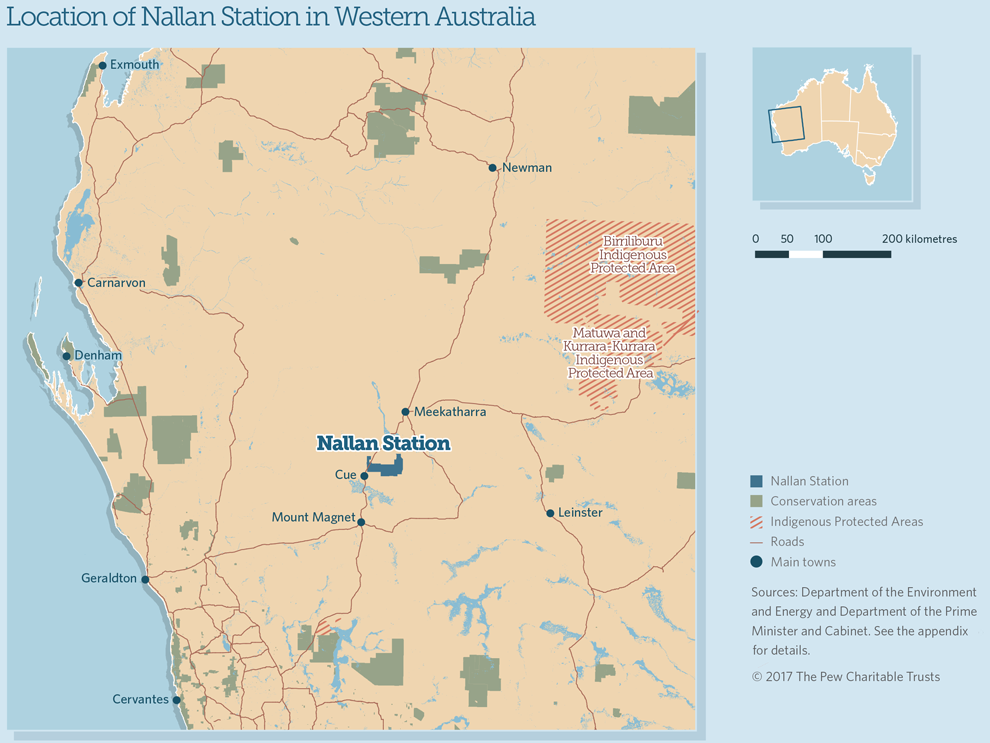

Clinch and his family have worked the country around Cue, in mid-west Western Australia, for four generations. It is land that has been changed by more than 100 years of gold mining and pastoralism. Overgrazing has stripped the more desirable vegetation, compacted the soil, led to erosion and created great crusts of salt across the landscape.

These legacies have left parts of the rangelands ragged and land managers like Clinch struggling.

“When we came here in 1999, it was mostly a bare piece of ground covered in salt,” Clinch says. It had been overgrazed to the point that it was “absolutely ground zero.”

But as Clinch asserts, “This is not waste country; it’s just country that’s been wasted. The problem’s been a hundred years in the making.”

Hope for Australia’s Heartland

New report “My Country, Our Outback” showcases successful land, marine management

These 3 Steps Could Save the Outback

Countering threats to nature in remote areas requires people, policy reforms and greater Indigenous involvement

This video is hosted by YouTube. In order to view it, you must consent to the use of “Marketing Cookies” by updating your preferences in the Cookie Settings link below. View on YouTube

This video is hosted by YouTube. In order to view it, you must consent to the use of “Marketing Cookies” by updating your preferences in the Cookie Settings link below. View on YouTube

Australia’s Outback spans 5.6 million square kilometres (2.2 million square miles)—an area that would encompass more than half of the United States or Europe. The Outback is one of the world’s few remaining great regions of nature. With landscapes stretching from scorching desert and rolling grasslands to lush forests and tropical beaches, the Outback is an area of extremes. Here, rivers still flow freely and native animals migrate across vast distances as they have for thousands of years.

This is Australia’s heartland, where the people and land embody much of what makes the country unique. The fate of the Outback could have international consequences, and Pew is working with a broad range of stakeholders including Indigenous people, scientists, conservation organisations, industry and government agencies to conserve these critical natural landscapes and marine habitats. It is the work of many of these people, and their connection to their country, that My Country, Our Outback explores in detail.

"We're still chasing the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow here, and that's perennial grasses," Clinch says. "Getting perennial grasses growing back between the shrubs, that's what this country really needs."

[Michael Clinch

For Clinch, creating an Outback that’s environmentally as well as economically sustainable has become a guiding passion.

“Locking up our land and leaving it has been proven to not be an option,” he says, referring to the hope among many people that the land could regenerate on its own. “The landscape simply needs controlled grazing to re-establish” and lead to a sustainable future for the rangelands.

The district’s hardiest perennial grass, woolly butt, had all but vanished from Nallan Station, 400 km north-east of Geraldton, when Clinch bought the property. “If there’s no woolly butt, you’re doomed,” he says. “That’s the toughest grass. If you have woolly butt degradation, it’s all over.”

He’s been looking for a sign that conditions are improving, specifically the return of perennial grasses, which Clinch calls “the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow” because proliferation of those grasses would indicate that the fragile soils here are regaining their health. “Getting perennial grasses growing back between the shrubs, that’s what this country really needs.”

As he’s speaking, Clinch spots something hidden among other vegetation: some slender stipa, which he calls “a Rolls-Royce of perennials.” Clinch can barely contain himself. “This is exciting. This is saying, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing.’ This is huge!”

Pastoralists manage 40 per cent of the Outback and, no matter their level of hard work and enthusiasm, they’ll need outside help to turn the region’s health around.

“We’re desperate to reclaim the quality and value of the Outback, and to achieve that vision, we need support,” Clinch says.

“We’re not asking for a handout, but by jeez, we’re asking for a hand up. We need capital injection; we need assistance to rebuild and restructure our grazing. If we don’t do it, who will?”

All Australians, and particularly people living in Australia’s coastal cities, should “seek to understand the value of the Outback,” Clinch says. “Come out and visit us and ask questions. And once we all understand, let’s get out there and do what needs to be done.

“We need to bring the Outback up front in our minds,” he says. “Give it a go!”

Barry Traill directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Outback to oceans program. Daniel Lewis is an Australian writer and author of 12 case studies included in My Country, Our Outback: Voices From the Land on Hope and Change in Australia’s Heartland.