National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska at Risk From Oil and Gas Development

BLM plan opens 18.6 million acres to potential drilling, other industry activities

This issue brief is part of a series outlining public lands in Alaska that are in danger of losing protection.

Overview

Since 2016, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service have advanced five efforts that would dramatically alter protections for some 60 million acres of federally managed land in Alaska. If fully enacted, the policies and decisions outlined in those proposed and finalized plans would open vast stretches of the Bering Sea-Western Interior, Tongass National Forest, Central Yukon, National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A), and unencumbered BLM land to extractive development and have significant impacts on Alaska’s lands, rivers, wildlife, and the Indigenous peoples who call these landscapes home.1

The complex value of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska

At 22.5 million acres, roughly the size of Indiana, the NPR-A comprises the largest contiguous block of public lands in the nation.2 This region of Alaska’s North Slope is the homeland of the Iṅupiat people, who have stewarded this landscape for thousands of years, and its vast wildlife, water, and other resources are essential to local communities’ existence and way of life.

President Warren G. Harding first designated the area as an emergency oil supply for the U.S. Navy by executive order in 1923, and the Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act (NPRPA) of 1976 transferred management of the reserve to the BLM.3 Since the act was first passed, Congress has repeatedly affirmed that, although energy development is an important reason to have and maintain the reserve, those activities must be balanced with “conditions, restrictions, and prohibitions” to protect its ecological, cultural, and recreational value and resources.4

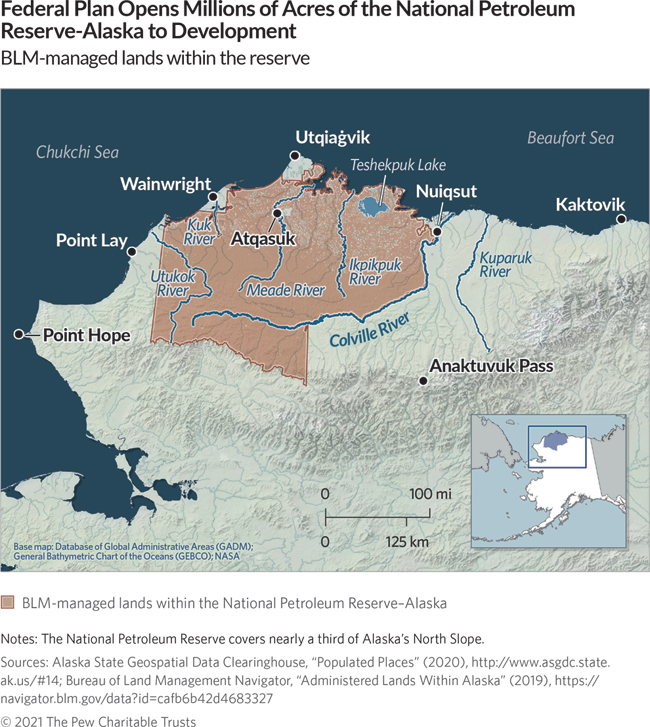

More than 40 Indigenous communities in northern and western Alaska depend on irreplaceable water, wildlife, and other resources supported by the reserve.5 Eight North Slope Borough communities—Utqiaġvik, Wainwright, Atqasuk, Nuiqsut, Point Lay, Point Hope, Kaktovik, and Anaktuvuk Pass—are located within or directly adjacent to the NPR-A and are inextricably linked to its future management. However, these communities have a complex relationship with that management because the revenue derived from development of oil, gas, and other resources underpins local government and Indigenous regional and village corporations while at the same time, surface resources such as wildlife and water are critical to Indigenous communities’ food security.

Management of the NPR-A

In 2013, the BLM’s planning effort yielded the NPR-A 2013 Integrated Activity Plan (IAP), which made roughly half of the reserve available for oil and gas leasing but excluded specific areas with important surface values, reinforcing the reserve’s dual mandate to protect critical ecological resources and provide certainty for industry.6 The 2013 IAP shielded about 11 million acres from development through creation of the Peard Bay Special Area and expansion of the Teshekpuk Lake and Utukok River Uplands special areas. These protections conserved nesting and breeding habitat for migrating bird populations from all seven continents and calving grounds for more than 300,000 caribou of the Western Arctic and Teshekpuk herds, which are vital to the Indigenous communities of northwestern Alaska. In addition, the plan included safeguards for riverine, lake, and coastal fish habitat; bays, inlets, and coastlines important for marine mammals; and coastal waters and river routes that North Slope residents rely on for hunting, fishing, berry picking, and trapping.

In late 2020, the BLM completed a revision to the NPR-A IAP, in response to former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s Secretarial Order of May 2017 directing the agency to strike “an appropriate statutory balance of promoting development while protecting surface resources.”7 If retained by the Biden administration, the updated IAP, which then-Interior Secretary David Bernhardt affirmed in January 2021, will open 82% of the NPR-A—18.6 million acres—to oil and gas leasing, dramatically altering management of the reserve’s special areas, including eliminating the Colville River Special Area and making the entire Teshekpuk Lake Special Area available for leasing.8

Recent discoveries of oil fields in the Bear Tooth and Nanushuk deposits in the Teshekpuk Lake area have substantially increased the likelihood of additional leasing and extraction in the NPR-A. This—combined with the impacts of climate change, which are highly pronounced in Alaska—reinforces the need for an Integrated Activity Plan that includes input from affected Indigenous communities, embraces traditional knowledge, and takes a conservative, precautionary approach to balancing energy development with “maximum protection” of significant biological surface resources as required by the NPRPA.9

Editor’s Note: This brief was updated on May 14, 2021, to correct the details in a photo caption.

Endnotes

- Bureau of Land Management, “Bering Sea-Western Interior RMP/EIS,” U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/programs/planning-and-nepa/plans-in-development/alaska/BSWI; Bureau of Land Management, “Central Yukon RMP/EIS,” U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/programs/planning-and-nepa/plans-in-development/alaska/central-yukon-rmp; U.S. Forest Service, “Alaska Roadless Rulemaking,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, https://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=54511; Bureau of Land Management, “National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska IAP/EIS,” U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/planning-and-nepa/plans-in-development/alaska/npr-a-iap-eis; Bureau of Land Management, “Revoking D-1 Withdrawals,” U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/programs/lands-and-realty/regional-information/alaska/d-1_withdrawals/revocation.

- Bureau of Land Management, “Arctic District Office,” https://www.blm.gov/office/arctic-district-office.

- Bureau of Land Management, “National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska,” U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.blm.gov/programs/energy-and-minerals/oil-and-gas/about/alaska/NPR-A; United States of America Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act of 1976, Public Law 94-258 (1976), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-90/pdf/STATUTE-90-Pg303.pdf.

- United States of America Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act of 1976, Public Law 94-258; United States of America Competitive Leasing of Oil and Gas—Title 42, Chapter 78, Section 6506a, https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title42-section6506a&num=0&edition=prelim.

- Alaska Department of Fish and Game, “Western Arctic Caribou Herd Update,” September 2016, https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=794.

- Bureau of Land Management, “National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska Integrated Activity Plan: Record of Decision” (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2013), https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/nepa/5251/42462/45213/NPR-A_FINAL_ROD_2-21-13.pdf.

- U.S. Department of the Interior Office of the Secretary, Subject: National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, Secretarial Order no. 3352 (2017), https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/so-3352.pdf.

- Bureau of Land Management, “Final Environmental Impact Statement Errata” (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020), 2, https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/117408/200284263/20027832/250034034/Final%20Environmental%20Impact%20Statement%20Errata.pdf; Bureau of Land Management, “National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska: Integrated Activity Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, Vol. 1” (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020), https://eplanning.blm.gov/public_projects/117408/200284263/20020342/250026546/Volume%201_ExecSummary_Ch1-3_References_Glossary.pdf.

- Division of Community and Regional Affairs, “Climate Change in Alaska,” Alaska Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development, https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/dcra/climatechange.aspx; United States of America Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act of 1976, Public Law 94-258.