Pennsylvania’s Historic Pension Reforms

How the new law reduces risks for taxpayers, ensures benefits for workers

A Metro bus turns a corner in Philadelphia in January 2017.

© Lexey Swall for The Pew Charitable TrustsPension reform legislation enacted this year in Pennsylvania with broad bipartisan support is historic in its scope and impact. The new law establishes what is known as a risk-managed hybrid plan for new employees that lowers costs and significantly reduces risk for taxpayers—while preserving a path to retirement security for public workers. At the same time, it maintains and extends the state’s commitment to fully fund the existing pension system and requires that the state evaluate policies to increase investment fee transparency and regularly perform stress test analysis to assess financial market risk.

Known as Act 5, the reform package will go a long way toward ensuring that the Keystone State’s retirement system is sustainable and secure for taxpayers and public employees for decades to come. Together, the Pennsylvania School Employee Retirement System (PSERS) and State Employees’ Retirement System (SERS) manage pension benefits for more than 730,000 employees and retirees.

This achievement did not happen overnight, and the challenges were extensive. For years, the state grappled with rising pension costs and huge unfunded liabilities. What had been a $20 billion surplus in 2001 became a $61 billion deficit by 2015. That swing of more than $80 billion over 15 years was among the largest recorded by any state.

The rising costs have been stretching state budgets and limiting investments in areas such as infrastructure, education, and public safety. After several years of failed attempts, Governor Tom Wolf (D), Senate Majority Leader Jake Corman (R), and other legislative leaders reached agreement on a reform package that passed the General Assembly with large bipartisan majorities. Wolf signed the measure into law June 12.

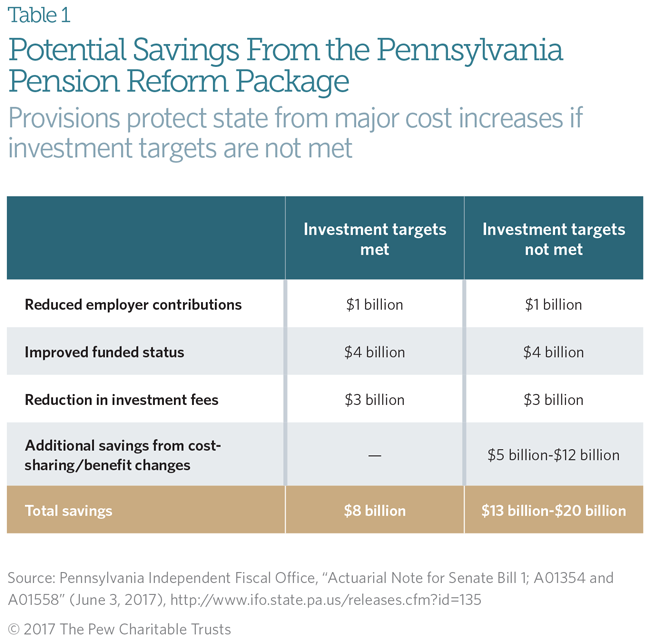

State analysts expect the reform package to save Pennsylvania taxpayers $8 billion to $20 billion over the next three decades, depending in part on the performance of plan investments. If the funds achieve their assumed rate of return, the state is projected to save $4 billion, and, in addition, improve its fiscal position by more than $4 billion over 30 years.

The new law protects taxpayers from additional costs if investment targets are not met. With the risk-managed hybrid system, taxpayers could save $5 billion to $12 billion in expected costs because guaranteed benefits have been reduced and employees will share some of the costs through higher contributions. Reductions in the fees paid for managing pension fund investments are expected to result in an additional $3 billion in savings. Table 1 breaks down the cost savings in the new plan under two scenarios: expected and low investment returns.

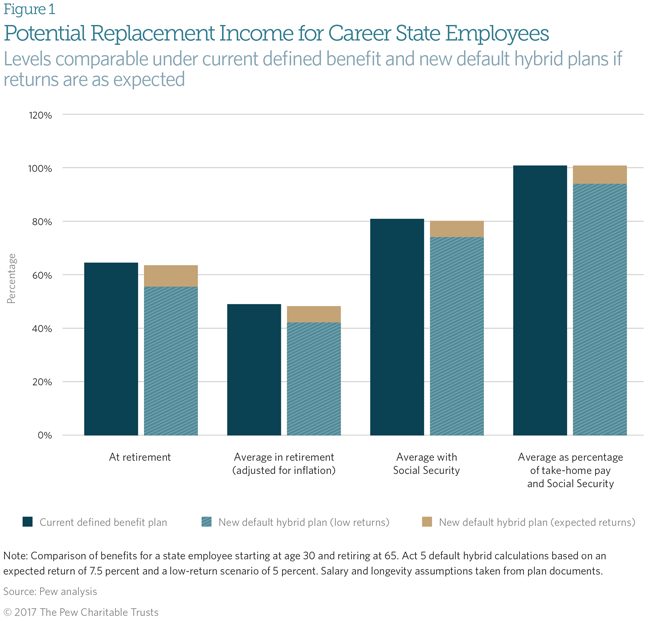

The new plan also continues to provide a path to retirement security for career workers in both state government and Pennsylvania’s public schools. On average, new workers can expect their retirement income to replace over 90 percent (including Social Security) of their final salary. Most research concludes that retirees will need 70 to 80 percent of pre-retirement income.

How the reforms will work

The law establishes a new benefit plan design for incoming members of SERS, the system for state employees except law enforcement officers, and PSERS, which represents public school employees. The reforms create a hybrid plan, which combines a reduced defined benefit (DB) program—the traditional pension—with a separate defined contribution (DC) savings account, like a 401(k). In addition, the legislation establishes an optional stand-alone DC plan.

Starting in 2019, new workers will be enrolled automatically in the hybrid plan, with the ability to select the DC option instead. Retirees will stay in the legacy pension plan, while current employees can choose the hybrid or DC plans or remain in the DB plan.

In the hybrid plan, employees and the employer contribute to both the DB and DC components. Employees contribute a total of 8.25 percent of total compensation, which is split between the two components. For SERS employees, 5 percent goes into the DB component and 3.25 percent into the DC component. For PSERS employees, 5.5 percent goes into the DB component and 2.75 percent into the DC portion. Employees also can select a different version of the hybrid plan with lower employee contributions and a slightly reduced benefit.

As the employer, the state government contributes an amount equal to 2.25 percent of the employee’s compensation to the DC component, resulting in a total DC contribution of 5 to 5.5 percent, depending on the system.

At retirement, workers receive guaranteed lifetime payments from the DB component based on their final average salary, years of service, and a multiplier of 1.25 percent to determine the size of the benefit. They also will have access to their DC savings accounts.

Several other important changes are included in the new law:

- The retirement age for new employees will increase from 65 to 67 starting in 2019.

- Final average salary will be calculated by averaging the five highest years of compensation rather than the three highest years.

- The new law does not apply to uniformed and hazard-duty state employees such as state police, corrections officers, and capitol police. Retired, current, and new public safety workers will remain in the current DB pension plan. These employees make up about a quarter of the state workforce.

A sustainable and secure retirement system

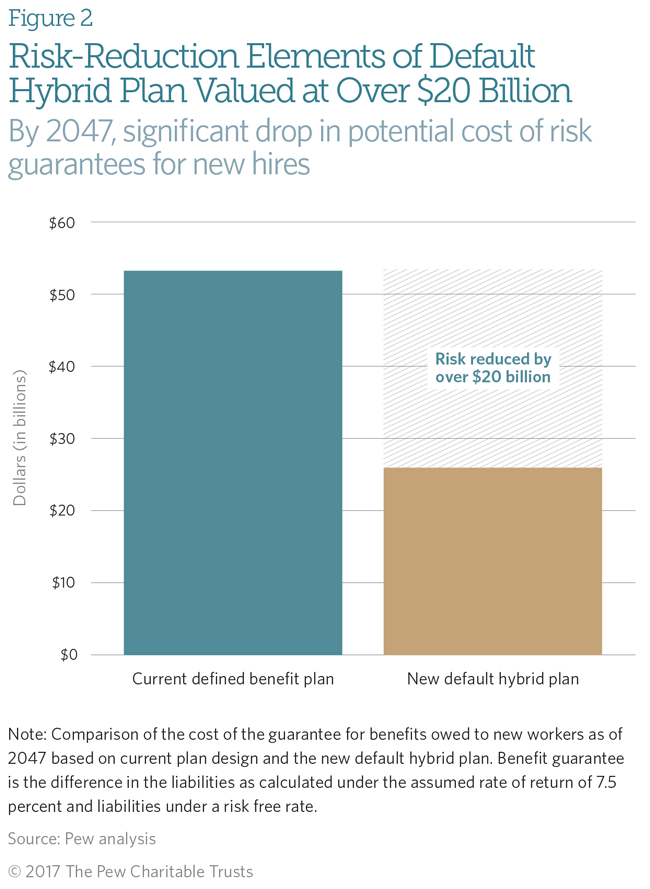

In addition to taxpayer savings and improvements in worker retirement security, the reforms help mitigate risk for the state and improve cost predictability.

Under the state’s traditional pension system, the government pays fixed sums to retired state employees, regardless of economic conditions. That has meant that the state’s obligation wasn’t reduced during times of economic recession or weak investment performance. So the state had to turn to other sources of income to keep making payments when investment returns were lower than projected.

Costs become more predictable under the new benefit structure because of added steps to mitigate risk. Cost-sharing provisions require pension holders to contribute more during times of economic distress and underperforming investments, thereby shouldering some of the burden. In addition, state costs are constant for the DC component regardless of investment performance because they are limited to the contributions. These factors should lower costs for taxpayers in the long run while fulfilling promises to state employees.

The new structure should be able to mitigate more than 60 percent of unplanned costs, making Pennsylvania one of only seven states with risk-reduction measures in place for at least half of costs. As a result, core government services in the state will be protected during economic downturns, and the need for dramatic budget cuts or tax increases will be reduced.

To enhance transparency and reduce fees paid to investment managers, the legislation also establishes a Public Pension Management and Asset Review Commission to make recommendations regarding active and passive investment performance and strategies.

State policymakers will still face difficult decisions in years to come to make required payments and balance their budgets, but the new law will reduce bloated investment costs and make Pennsylvania less vulnerable in economic downturns. As The Pew Charitable Trusts told state legislators in recommending passage, the elements of the package together represent “one of the most—if not the most—comprehensive and impactful reforms any state has implemented.”

Greg Mennis is director of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public sector retirement systems project.