Navigating Global Shark Conservation Measures: Current Measures and Gaps

A new analysis by the Pew Environment Group, Navigating Global Shark Conservation Measures: Current Measures and Gaps, compiles existing management measures for sharks, highlights their inadequacies, and makes recommendations for improvements. The following is a summary of that analysis.

Sharks have been swimming the world's oceans for more than 400 million years. But today, shark populations are in trouble globally. Life history characteristics, such as slow growth, late maturation, and production of few offspring, make sharks vulnerable to overfishing and slow to recover from decline. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species has assessed the extinction risk of 480 species of sharks from around the world. Forty-three percent (209 species) are data deficient. More than half of those with enough information to determine their conservation status (150 species) are threatened or near threatened with extinction. The loss of sharks could cause irreversible damage to the ocean, as sharks play an important role in maintaining balance in the marine environment.

Shark species not only span national jurisdictions, but also roam the high seas, thus complicating conservation and management efforts. Globally, the existing state of management for sharks is inadequate to protect these animals. Shark conservation and management is a piecemeal approach of varying measures at the domestic, regional, and international levels.

Fishing to Supply a Global Market

Shark fishing occurs around the globe, but little is known about the magnitude of the fishing or the catch. Evidence shows that actual global catch of sharks may be three to four times higher than the official statistics reported by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

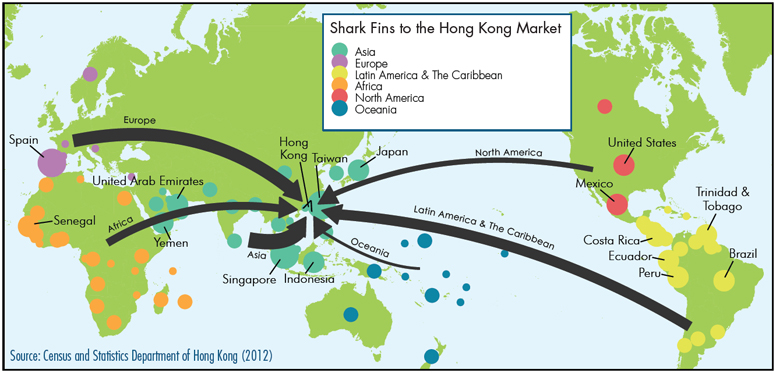

Shark fishing globally is largely driven by the demand for shark fins. Hong Kong, the world's largest shark fin market, represents approximately 50 percent of the global trade. According to trade data from the Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong, 83 countries exported more than 10.3 million kilograms (22.7 million pounds) of shark fin products to Hong Kong in 2011.7 With shark fishing countries from around the world supplying fins to the Hong Kong market, effective shark management must be global, including all areas where sharks are caught.

Tools for Managing Sharks

The International Plan of Action for sharks (IPOA-Sharks), the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) are the three primary tools for conservation and management of sharks on a global level.

On the regional level, regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) should play a critical role in regulating fishing for certain highly migratory and straddling stock species, including sharks, to ensure that relevant fisheries are sustainable.

Countries, territories, and other political entities can take action to manage and conserve sharks in their waters. Some countries have passed laws or put in place regulations that prohibit commercial fishing of all sharks throughout their exclusive economic zone, creating a shark sanctuary. Other domestic measures include banning the sale, trade, and possession of shark parts, prohibiting shark finning, putting in place catch quotas, prohibiting retention of vulnerable species, and establishing gear restrictions.

The Gaps

Current shark conservation and management measures range from the local to international levels, with some protections covering all species and others that are specific to only certain species. This has resulted in an inconsistent patchwork approach that does not adequately protect sharks. Key deficiencies identified in the Pew Environment Group analysis of shark conservation measures include:

Current shark conservation and management measures range from the local to international levels, with some protections covering all species and others that are specific to only certain species. This has resulted in an inconsistent patchwork approach that does not adequately protect sharks. Key deficiencies identified in the Pew Environment Group analysis of shark conservation measures include:

- Only thresher sharks, oceanic whitetip sharks, hammerhead sharks, silky sharks, spiny dogfish, porbeagle sharks, basking sharks, and 17 species of deep-sea sharks have any conservation or management measures at the RFMO level, and then they are often protected only by some RFMOs and not others. Considering that there are more than 450 species of sharks and that most are highly migratory and routinely cross political boundaries, more action by RFMOs is required to conserve and protect these ocean predators.

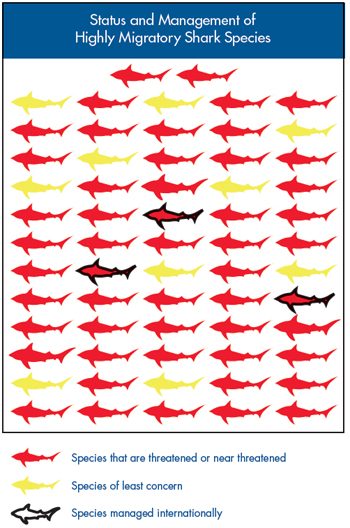

- Of the 62 highly migratory shark species with enough data to allow for a full assessment, 82 percent (51 species) are considered threatened or near threatened by IUCN. Despite the poor conservation status of global shark populations, only three species, the basking, whale, and great white shark, have any global management measures in place.

- Despite the poor status of many shark species and the benefits CITES can provide to shark populations, only three species—the basking, great white, and whale shark—are included in the CITES Appendices.

- Only two shark species, the basking shark and great white shark, have the highest level of protection by CMS, an Appendix I listing, which includes a prohibition on take. Five additional species are listed on CMS Appendix II, which identifies those species that need or would significantly benefit from international cooperation. In addition to only having seven shark species included in CMS Appendices, these instruments are relatively new and the benefit of these measures is still to be demonstrated.

- To date, just 54 countries have developed National Plans of Action (NPOAs) for sharks. NPOAs identify issues that need to be addressed, but vary in terms of comprehensiveness and implementation.

- A review of 211 countries, territories, and entities found that only approximately one-third ban the wasteful practice of finning and very few countries have catch limits in place for individual shark species (even for threatened or endangered species).

- Monitoring of shark catches and trade is poor. Evidence shows that actual global catch of sharks may be three to four times higher than the official statistics reported to FAO. One-third of the total shark, ray and skate landings were reported poorly as just “sharks, rays, skates, etc.,” rather than by the species name or even by “shark,” making it nearly impossible to know exactly how many sharks are being landed and undermining the ability to sustainably manage shark fisheries.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Precautionary national, regional, and international protection measures to conserve sharks are urgently needed. The Pew Environment Group calls on all countries, territories, and entities to improve shark conservation and management by acting now to end unmanaged and unsustainable shark fishing and to regulate trade in threatened sharks.