Unearthing the Mysteries of Hubbard Point

When we arrived at Hubbard Point after an hourlong, bumpy boat ride from our lodge through the open waters of Canada’s Hudson Bay, it was obvious why generations of Inuit have considered this a special place. From the boats, we counted 11 polar bears roaming the point. A large pod of beluga whales churned up the waters nearby, and seabirds flew overhead.

Once our guides, who also served as bear guards, had given the all-clear that it was safe to venture out of the boats and up to the point, the magic was even more apparent. Even my untrained eye could see evidence of human presence everywhere: old tent rings, food caches, graves.

Jeremy Davies is the marine spatial analysis manager for Pew’s International Arctic Ocean project and lives in Bellingham, Washington.

Scattered about were the bones of whales, seals, caribou, and seabirds—signs of the area’s bounty. Add to this the 360-degree vista afforded by the elevation of a gravel ridge, and Hubbard Point is the perfect location for a seasonal camp, a fact known to indigenous people for at least 1,000 years.

In July, our seven-member team traveled to the point, 71 kilometres (44 miles) north of Churchill, Manitoba, to conduct a weeklong archaeological survey of how Inuit and their Thule ancestors have used this biologically productive area where land and sea meet.

The project was a partnership between the Inuit Heritage Trust and Oceans North Canada, a collaboration of The Pew Charitable Trusts and Ducks Unlimited. This is the third year that we have conducted research in the Seal River region of western Hudson Bay, where one of the world’s largest beluga whale populations gathers each summer.

The data are helping to build a case for establishment of a beluga management plan in this area, an effort under discussion by local communities and the Manitoba government. In 2012, our science team helped tag six beluga whales to study their movements along the coast and the timing of their seasonal migration. The next summer, we conducted boat-based line-transect surveys to examine how belugas and seabirds use the Seal River estuary.

This year, our team consisted of Virginia Petch, an archaeologist; Kristin Westdal, a marine biologist for Oceans North Canada; two Inuit elders, Peter Alareak and Luke Suluk, from Arviat, Nunavut; Johnny Mamgark, a hunter and guide based in Rankin Inlet; David Tassiuk, a high school student from Arviat who earned credits toward his diploma on this project; and me, an ecologist and mapping specialist for Pew’s international Arctic project.

Our Inuit team members were especially excited, hoping to unearth old tools and bones linking them to their ancestors. After a long day of getting oriented with the site, we headed back to the Seal River Lodge, 25 kilometres (15 miles) south, our home base for the week. In polar bear country, camping on-site poses too great a risk to bears and humans alike.

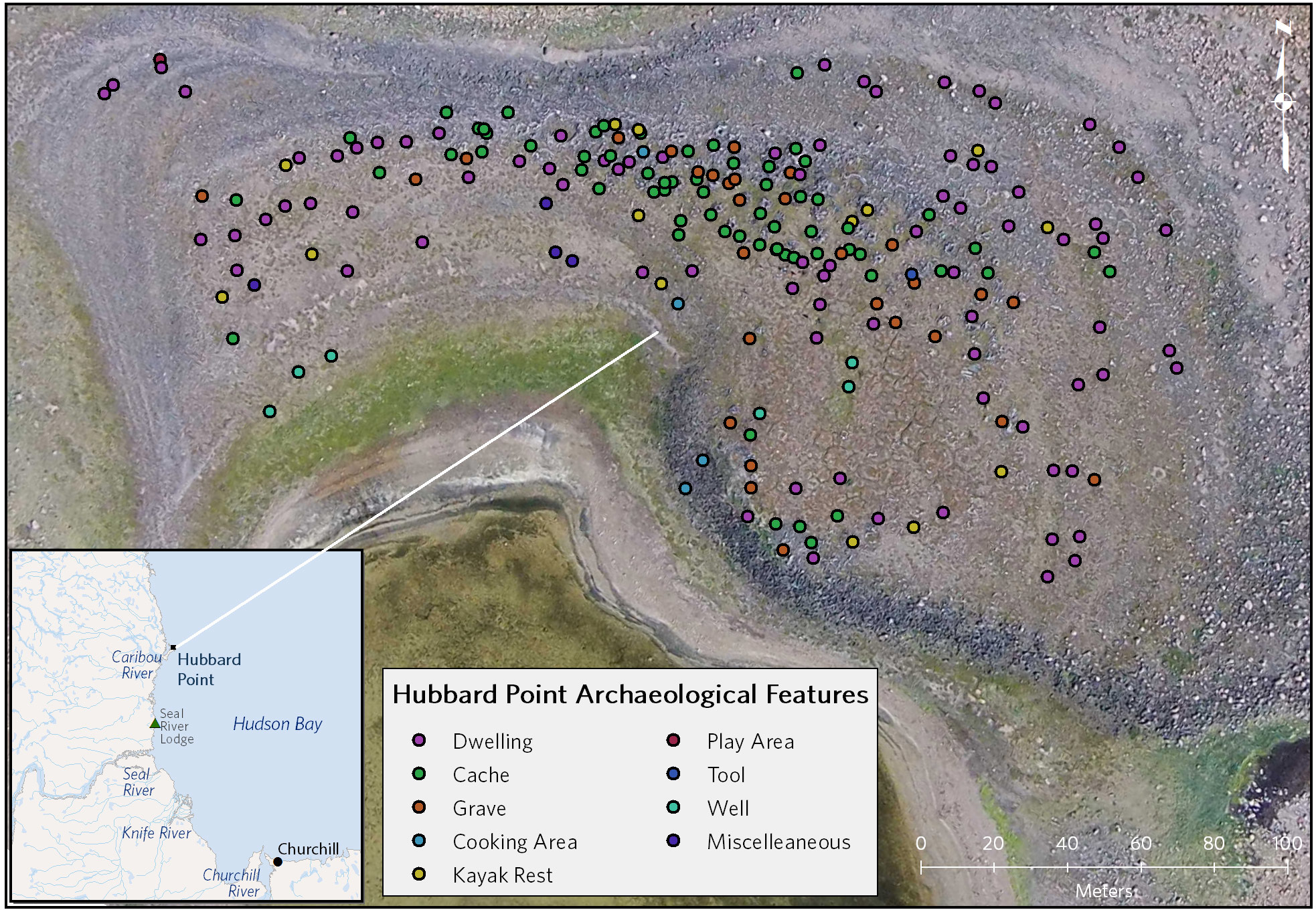

Over the next three days, we flagged, mapped, and photographed 207 signs of human presence in the four-hectare (10-acre) area, which is one to 18 metres above sea level. These included tools, graves, food caches, kayak rests, cooking areas, wells, play areas, and dwellings. I mapped the locations, often accompanied by Peter, who identified the various features and shared his rich traditional knowledge and contagious laughter.

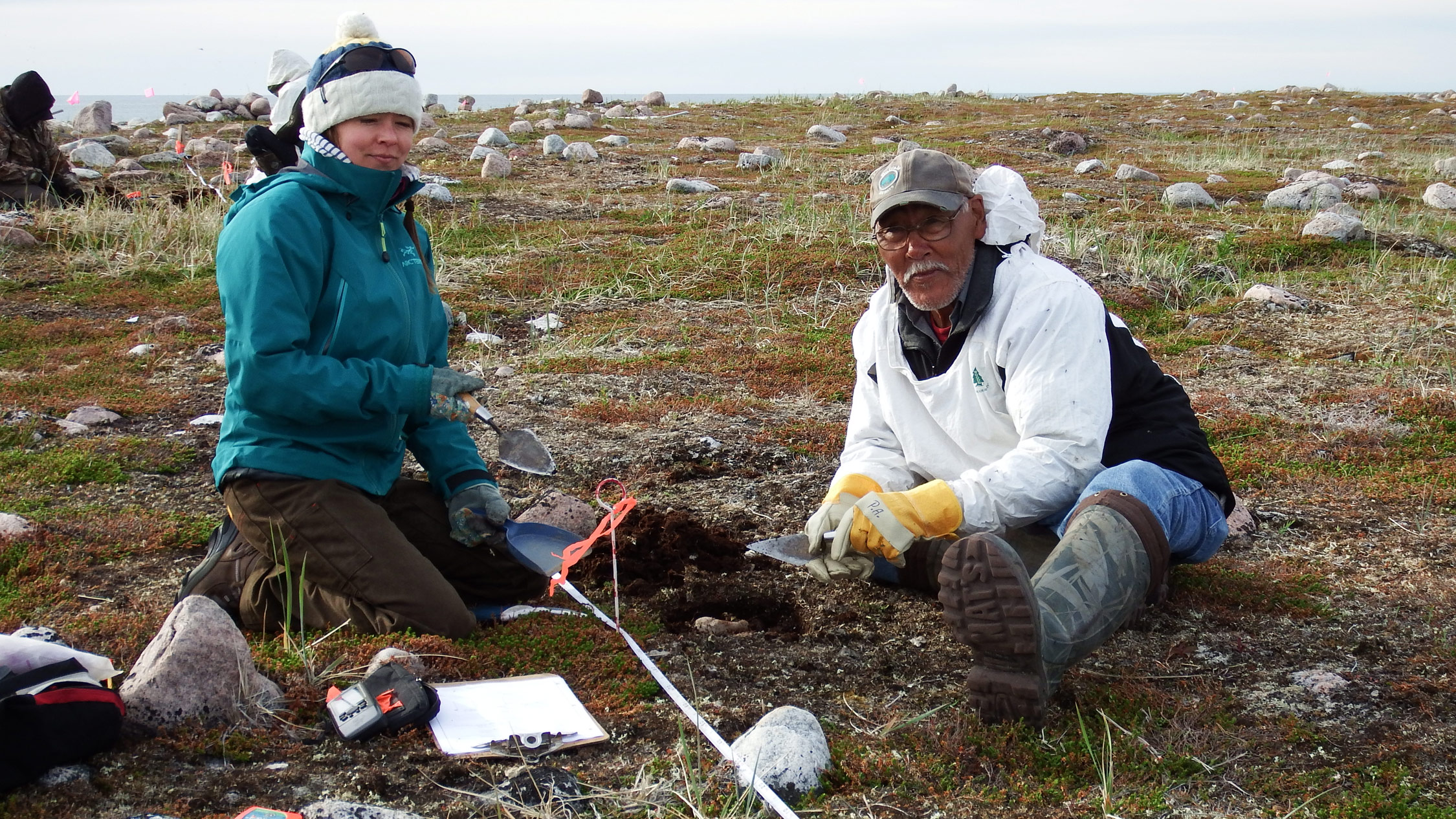

Others conducted systematic “shovel tests”—excavations of 50-square-centimetre (eight-square-inch) plots at regular intervals along established survey lines. Virginia, who has led archaeological work at indigenous sites around Canada for more than three decades, designed the surveys in accordance with scientific standards.

These tests proved fruitful right away. Kristin and Peter found bones from a variety of species. Artifacts discovered at the excavation sites, including animal bones, tools, and charcoal from fire pits, were catalogued and bagged for later analysis. As is the standard with such surveys, human remains were not touched or removed, out of respect for the deceased and Inuit tradition.

Virginia selected a few sites, with advice from Peter, Luke, Johnny, and David, for comprehensive survey and excavation. These included a subterranean dwelling and what was probably a large multifamily longhouse. Enduring relentless attacks from mosquitoes and flies, we found many more flakes, tools, and bones.

The weather began to turn toward the end of our fourth day of surveys. Because of our long commute to the point, wind was our worst enemy. The waves grew by the hour, driven by the strengthening northeast winds, so we pulled our survey markers and returned to the lodge, not knowing if we would make it back. As it turned out, that was the end of our digging for the season; wind and rain persisted for the rest of our visit.

Back in the lodge, Virginia and others set about preparing the samples for radiocarbon dating and other analyses. I began creating a database of the documented features and generating digital maps via GIS, or geographic information system. As we worked, we saw polar bears converge on a recent seal kill nearby. Following a social hierarchy unknown to us, bears took their turns gorging on the carcass, leaving when they had their fill or were driven off by others.

By the end of the week, we had documented and mapped the locations of more than 200 features and unearthed dozens of artifacts.

More analyses are planned, but initial radiocarbon dating of one caribou bone found in a dwelling cooking area estimated its age at 980 years. This corresponds with late Thule people and, combined with other features found at the site, reinforces the historical significance of the area to the Inuit of western Hudson Bay.

Inuit members of our team talked about their love of the area and their strong desire to protect it for their children and grandchildren. Exploring Hubbard Point’s amazing vistas, teeming life, and rich history left a lasting mark on me as well, strengthening my appreciation for the wildness and beauty of the Arctic.