The Theranos Problem Congress Must Still Solve — Patients Need Protection

For most of its existence, the now-defunct biotech startup Theranos operated in so-called “stealth mode” — disclosing little about the science behind its blood-testing device while boldly claiming that it could deliver faster, more convenient, and cheaper diagnostic tests to millions of people anxious to know if they had diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, or scores of other conditions.

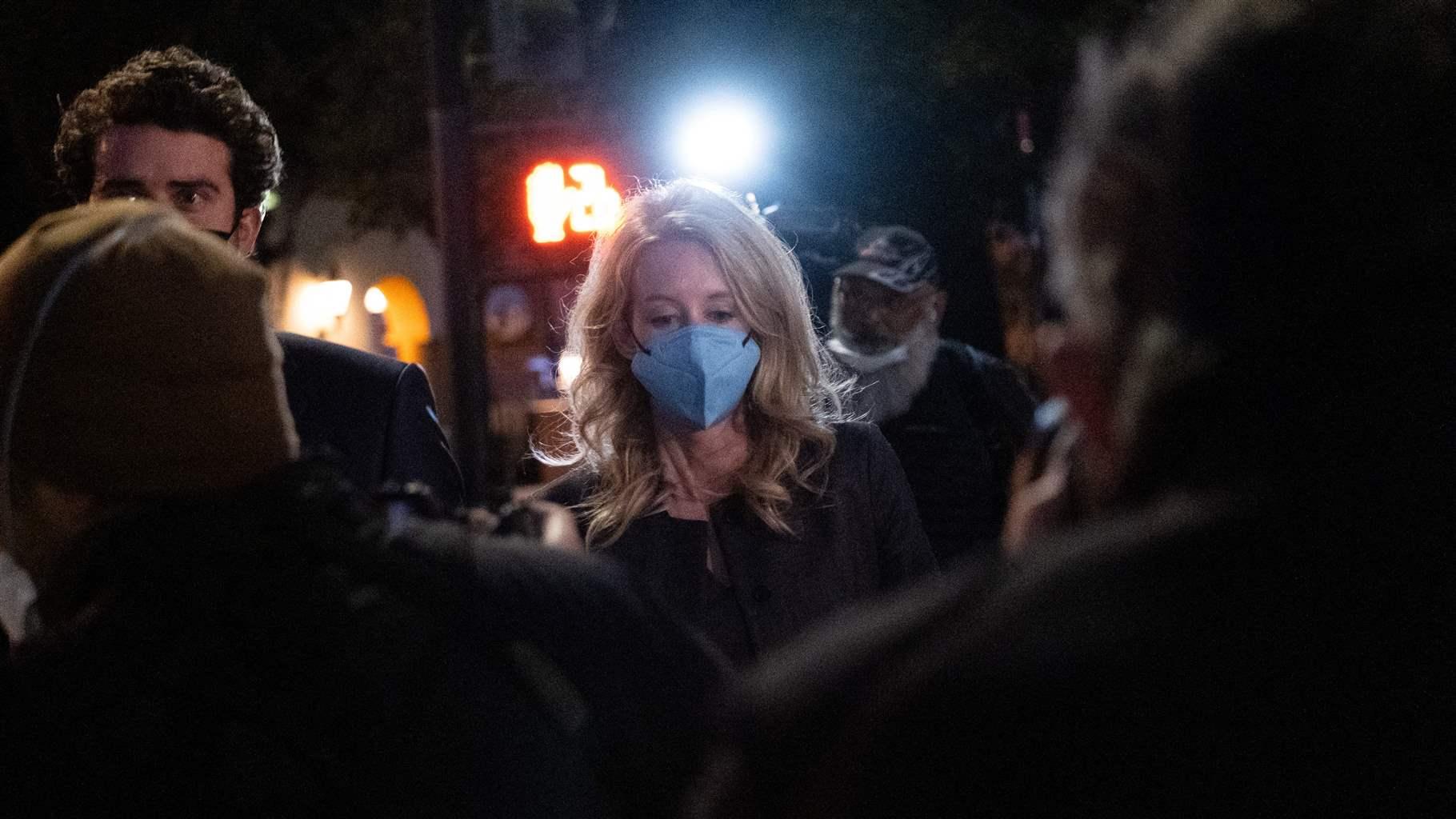

In truth, Theranos’ testing devices didn’t work as advertised, a fact the company managed to conceal from investors, regulators, and customers for years until whistleblowers and a journalist exposed the firm’s misconduct. Theranos was then forced to invalidate two years’ worth of blood tests for tens of thousands of patients, and, on Monday, its executive Elizabeth Holmes was found guilty on four charges of defrauding investors, facing up to 20 years in prison.

But even though Theranos’ leaders have been called to account, the loophole they exploited to avoid independent review of their devices remains wide open, and now Congress must act to close it.

Unfortunately, House and Senate committee leaders have yet to take up a bipartisan bill, known as the Verifying Accurate Leading-edge IVCT Development (VALID) Act, that could plug the holes in testing oversight and ensure that diagnostic products are accurate before they’re used on patients.

When Congress authorized the Food and Drug Administration to regulate medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic tests, in 1976, the agency waived regulatory requirements for tests designed, manufactured, and used all in the same lab — known as lab-developed tests. This approach made sense decades ago, when LDTs tended to be relatively simple and were intended for small patient populations; they were designed to detect rare conditions for which there were few or no other commercially available diagnostics. But as the Theranos experience has shown, today’s LDTs are often more complex, designed for conditions as widespread as cancer or COVID-19, created to compete with FDA-approved tests, and marketed nationally, in some cases for consumers to use in their homes without medical oversight.

If FDA had required Theranos to submit its LDTs for premarket review, as it does for other diagnostics, the agency might have been able to shield patients from harm. It could have kept Theranos products off the market and restricted the company’s unsupported marketing claims. And even if Theranos had been able to clear that initial FDA review, mandatory adverse event reporting could have enabled FDA to identify faulty tests sooner and recall them, if necessary.

But the public safety story here is not just a Theranos story. Other companies exploit the same regulatory gaps, and many people suffer after receiving false results from faulty LDTs that lead them to undergo the wrong treatment or forgo the right one.

Unfortunately, there’s little transparency in the LDT marketplace. As research from The Pew Charitable Trusts demonstrates, without FDA oversight before and after a test comes to market, or even a simple product registry, no one knows precisely how many LDTs are in use, let alone how often they fail or how many people they hurt.

That needs to change. It shouldn’t be left to whistleblowers and investigative journalists to identify LDT problems piecemeal after they occur; instead, patients and their health care providers deserve more information about the tests they rely on to diagnose life-changing and life-threatening conditions. And Congress needs to make it clear that oversight should lie with FDA.

The agency needs clear authority and resources to prevent harm; the track record shows that when it exercises its authority over diagnostics, patients and test-makers benefit alike. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, FDA exercised its “emergency use” authority to review 125 COVID-19 LDTs. It found serious “design or validation problems” in 82 of those tests. In most cases, FDA worked with developers to rectify the issues and bring the much-needed products to market.

In the past, some labs strongly objected to FDA oversight of LDTs, but since then they’ve worked with members of Congress to seek solutions through the VALID Act. Unlike earlier proposals, the bill has benefited from several rounds of substantive input from test manufacturers, clinical laboratories, and patient groups. And unlike previous debates around reform, there’s wide agreement across many labs and device manufacturers about VALID’s major provisions, with discussion focusing more on how regulatory oversight should be reformed — not whether it should be reformed.

The bill’s not perfect. It exempts too many devices from premarket review, and it doesn’t provide FDA with enough tools to take action against poor quality tests once they’re in use. Health committee leadership in Congress should work together to build on VALID’s framework and make it stronger, and as chair of the House committee, New Jersey Rep. Frank Pallone can be a powerful voice. Congress can give FDA authority to review all diagnostics based on the risk they pose to patients before they reach the market and monitor their performance once in use.

This requires swift action. Congress has a window of opportunity to attach the VALID Act to another bill, a so-called “must-pass” measure on user fees for medical devices that lawmakers plan to approve in 2022.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Theranos trial both demonstrate the urgency of the problem. The longer Congress waits, the longer patients will remain vulnerable to faulty tests. When it comes to medical tests, we need safety and sunlight, not stealth — and we need it now.

Liz Richardson directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ health care products project.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com on Jan. 12, 2022.