Palau National Marine Sanctuary

Building Palau’s future and honoring its past

This fact sheet was updated in June 2017 to reflect the designation of additional large marine reserves in 2016.

Caring for the environment has long been an important part of Palau’s culture. For centuries, traditional leaders on these Pacific Ocean islands have worked to protect local waters through enactment of a “bul”—a moratorium on catching key species or fishing on certain reefs to protect habitats that are critical to the community’s food security.

When Palau became an independent nation in 1994, its founders wrote in the constitution about the need for “conservation of a beautiful, healthful, and resourceful natural environment.”

Palau’s waters are worth protecting. Commonly referred to as one of the seven underwater wonders of the world, they boast ecosystems of remarkable biodiversity, which include:

- More than 1,300 species of fish.

- More than 400 species of hard coral and 300 species of soft coral.

- Seven of the world’s nine types of giant clam.

- Lakes that are home to nonstinging jellyfish.

- The most plant and animal species in Micronesia.

Palau is again taking a leading role by moving to create a modern-day bul that puts the marine environment first. On Oct. 28, 2015, after unanimous passage in the National Congress, President Tommy E. Remengesau Jr. signed into law the Palau National Marine Sanctuary Act, establishing one of the world’s largest protected areas of ocean.

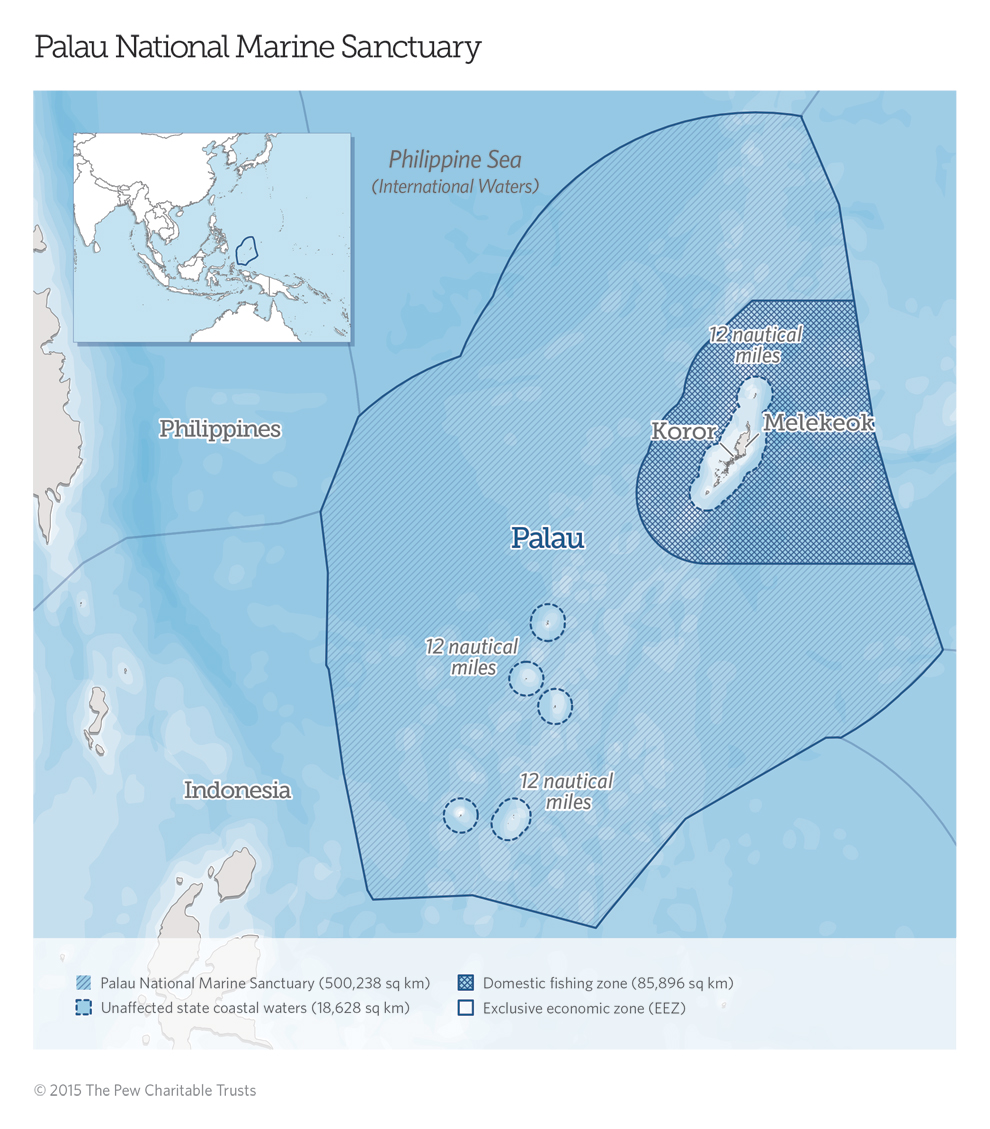

The sanctuary will fully protect about 80 percent of the nation’s maritime territory. Full protection means that no extractive activities, such as fishing or mining, can take place. The reserve covers 500,000 square kilometers (193,000 square miles)—an area bigger than the U.S. state of California.

The Pew Charitable Trusts

The Pew Charitable Trusts Richard Brooks/The Pew Charitable Trusts

Richard Brooks/The Pew Charitable TrustsDiving injects about $90 million a year into Palau’s economy.

To ensure the sustainability and feasibility of this massive endeavor, the sanctuary will be phased in over a five-year period. A separate zone reserved for local fishermen and small-scale commercial fisheries with limited exports will cover the remainder of Palau’s waters. Coastal waters from shore to 22 kilometers (12 nautical miles) will not be affected and will be managed under current regulations.

Good for the economy

Well-run sanctuaries are scientifically proven to expand fish stocks and, as a result, increase local fishing.1 The Palau sanctuary will provide fish not only for the local market but also for the growing tourism market. This will redirect to local fishermen and businesses income that once went to importers.

Good for tourism

By maintaining a vibrant marine environment, the sanctuary designation can attract divers and other high-value tourists. Surveys by the Palau Visitors Authority indicate that divers who travel to Palau independently—not as part of package tours—spend around eight times more than other types of tourists. Diving generates about $90 million a year for the economy, an amount equal to about 40 percent of Palau’s gross domestic product.2

Good for the environment

Globally, many fish stocks are in serious decline. Fully protected marine areas are a critical tool for addressing challenges to ocean health. They provide a broad range of benefits by safeguarding biodiversity, protecting top predators, and maintaining ecosystem balance. The Palau National Marine Sanctuary will also bring benefits to neighboring Pacific ecosystems because healthy species migrate into nearby waters. Highly protected areas have proved to be six times more resilient to the effects of climate change than unprotected areas.3

The sanctuary also will help protect Palau’s waters from illegal fishing. Marine surveillance experts from around the world are collaborating with Palauan authorities on a world-class enforcement strategy to monitor the marine zone. The sanctuary will make it easier to identify and stop illegal fishing, because restrictions on commercial activity simplify detection.

In 1994, the same year Palau became independent, it passed the Marine Protection Act, which included a moratorium on fishing for bumphead parrotfish.

© Wolfgang Poelzer/Getty Images

© 2009 National Geographic

© 2009 National Geographic Shutterstock

ShutterstockThe Rock Islands, a UNESCO World Heritage site, include 445 uninhabited limestone islands of volcanic origin.

Conclusion

Palau’s growth is deeply tied to its conservation legacy. Tourists from around the world are drawn to these islands in the western Pacific for their unparalleled beauty. By safeguarding marine life through the sanctuary, Palau strengthens its reputation as a sustainable tourism destination, and that brings extensive economic and environmental benefits. The Palau National Marine Sanctuary ensures a vibrant future for the nation’s marine life and for its economy for years to come.

Island communities have been among the hardest hit by the threats facing the ocean. Creating this sanctuary is a bold move that the people of Palau recognize as essential to our survival. We want to lead the way in restoring the health of the ocean for future generations.Tommy Remengesau Jr., president

Richard Brooks/The Pew Charitable Trusts

Richard Brooks/The Pew Charitable TrustsIn 2009, Palau created the world’s first shark sanctuary.

About Global Ocean Legacy

Global Ocean Legacy, a project of Pew and its partners, worked with local communities, governments and scientists around the world to protect and conserve some of our most important and unspoiled ocean environments. Together they established the world’s first generation of great marine parks by securing the designation of large, highly protected reserves. From 2006 through 2016, GOL helped secure commitments to protect 2.4 million square miles (6.3 million square kilometers) of ocean—an area 12 times the size of Central America.

Endnotes

- Enric Sala et al., “A General Business Model for Marine Reserves,” PLOS ONE 8, no. 4 (2013): e58799, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058799.

- Gabriel M.S. Vianna et al., “Wanted Dead or Alive? The Relative Value of Reef Sharks as a Fishery and an Ecotourism Asset in Palau,” Australian Institute of Marine Science and University of Western Australia (2010), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2011/05/02/ Palau_Shark_Tourism.pdf.

- Peter J. Mumby et al., “Operationalizing the Resilience of Coral Reefs in an Era of Climate Change,” Conservation Letters 7, no. 3 (2014): 176–87, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/conl.12047.