The Municipal Liquidity Facility: How It Works

Federal Reserve program created in April is a new financing source for state and local governments

This fact sheet was updated to reflect that the data in Figure 2 is as of Oct. 2.

Overview

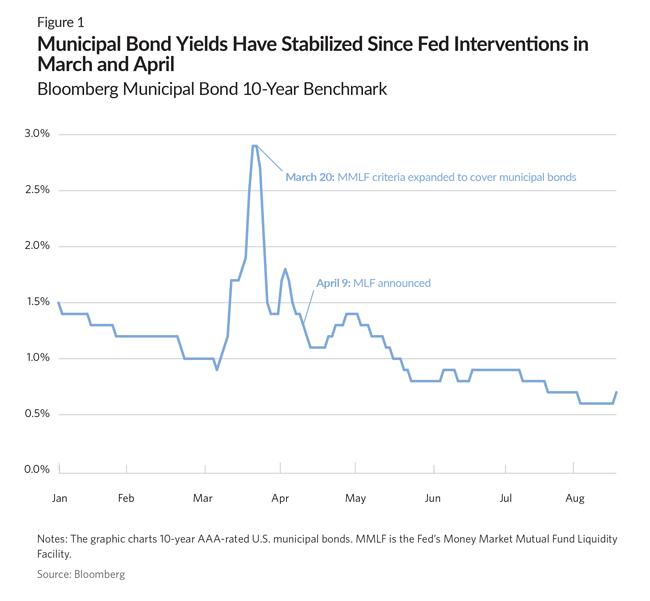

The Federal Reserve created the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) in April to address a sudden liquidity crisis in municipal markets that caused a sharp rise in interest rates on municipal securities. The program establishes the Federal Reserve as a source of emergency financing for state and local governments to ensure that they have access to credit to manage revenue delays and losses during the COVID-19 pandemic. The creation of the facility signifies the first time that the Fed has directly purchased bonds from state and local governments in a lender-of-last-resort capacity.1

Municipal credit markets have largely stabilized since the MLF’s announcement in April, with bond pricing returning to pre-pandemic levels. As a result, only a small fraction of the program’s $500 billion authorization has been used. This is largely because the program’s borrowing rates are set to be attractive only in times of emergency, when interest rates in the municipal markets typically spike.

State and local officials should nonetheless understand how the MLF can be used and where the program may be headed. Although municipal credit markets have largely recovered from the unprecedented turbulence in March, the longer-term economic outlook remains unclear. If credit conditions deteriorate again, the MLF could be an attractive option for many more states and localities.

How does the program work?

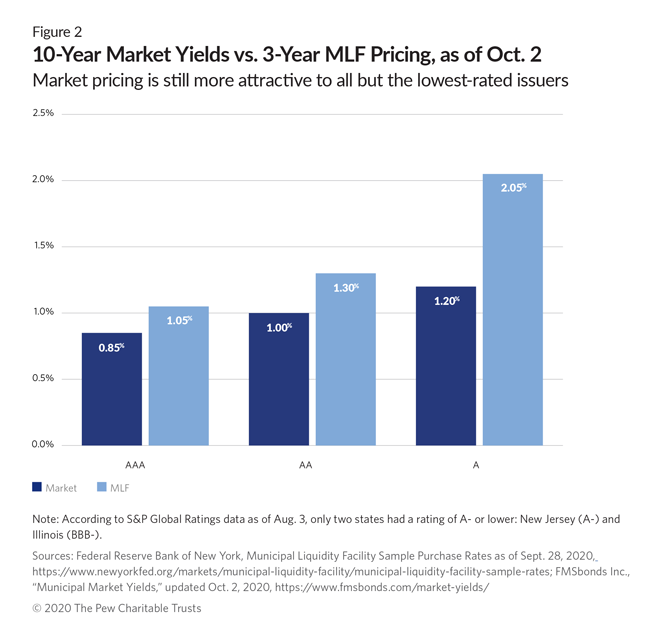

The MLF is authorized to purchase up to $500 billion in short-term notes from eligible governments and public entities, with terms of up to three years, through December 2020. Sales are conducted through a special purpose vehicle that the Federal Reserve created for the program. Eligible participants can sell debt to the MLF either through a competitive auction—with the MLF serving as a backstop if market demand is insufficient—or directly to the facility. If the issuer chooses to sell directly to the MLF, it must certify that it cannot access better rates on the private market. As Figure 2 shows, 10-year market yields are now more attractive for most highly rated municipal issuers. Three-year market yields would typically show an even greater gap in pricing.2

Who can participate?

Eligible participants include:

- All 50 states and Washington, D.C.

- Cities with a population greater than 250,000

- Counties with a population greater than 500,000

- Up to two revenue-bond issuers (RBIs) per state, including public agencies and authorities that issue bonds backed by specific revenue streams (e.g., transit authorities)

- Multistate entities formed with approval from Congress

In states with fewer than two eligible cities and counties, the governor may designate up to two additional participants.3; State, city, and county issuers must generally be rated investment grade to participate; RBIs and multistate entities must be rated A- or higher.

Under the program’s original terms, only cities with a population greater than 1 million and counties with more than 2 million residents could participate.4 The Federal Reserve broadened the criteria in April and June following criticism that the original eligibility requirements could unintentionally exclude many important metropolitan areas and potentially exacerbate economic inequalities.5

How much can be borrowed?

States, cities, and counties may borrow up to 20% of their fiscal year 2017 own-source revenue (OSR), including utility revenue, in one or more transactions. OSR is a measure of revenue tracked and reported by the U.S. Census Bureau that includes taxes and fees controlled by the state or local government. Each entity’s loan limit can be found in Appendix A of the loan terms on the Fed’s website.6

What can the money be used for?

The Fed created the MLF “to help state and local governments better manage cash flow pressures in order to continue to serve households and businesses in their communities.”7 Initially, this aim included using the program to help bridge the delay in revenue collections caused by the extensions of tax filing deadlines nationwide.

Now, the program is intended to have three main uses:8

- To help manage the impact of cash flow pressures related to further delays in tax receipts

- To lessen the impact of revenue reductions owing to diminished economic activity and offset increases in costs associated with fighting the pandemic

- To help the borrower make debt service payments on existing obligations

These broad usage criteria, combined with an extension of the maximum loan term from two to three years, have potentially changed the character of the MLF from a program originally focused on short-term cash flow issues to a facility that might be considered for budget borrowing. For example, as Pew’s analysis for New Jersey showed, revenue anticipation financing could be used to smooth revenues over the downturn and expected recovery, providing resources to preserve core services and replenish reserves in the near-term. The debt could then be repaid from higher levels of revenue generated once the economy has begun to recover.9

Which kinds of notes can be issued?

A variety of short- and medium-term notes—including tax anticipation notes, tax and revenue anticipation notes, bond anticipation notes, and revenue anticipation notes—can be issued.

What is the cost?

Interest rates are based on an index—the overnight index swap rate—that tracks the effective federal funds rate (which currently hovers near 0 basis points) plus an “applicable spread” ranging from 100 (AAA) to 330 (BBB-) basis points depending on the issuer’s credit rating. For taxable securities (i.e., notes on which paid interest is subject to federal or state income taxes), the rate is equal to that amount divided by 0.70. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York publishes weekly updates on available MLF interest rates. The latest update on Sept. 28, which includes a 50-basis-point reduction in borrowing costs compared with the original pricing schedule, can be found on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s website.10

Interest rates on new debt issues can often be higher than prevailing yields in the secondary market. This could mean that, for some borrowers, the MLF may actually be slightly more attractive than what current yields show, especially for issuers on the lower end of the credit rating spectrum.

Borrowers must also pay a 10-basis-point origination fee and establish a repayment schedule within the three-year allowable term.

Which states or localities have used the program?

Illinois was the first to participate, selling $1.2 billion in one-year securities to the MLF in June.11 On Aug. 18, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in New York became the second participant, employing the MLF as a backstop after declining all bids for a new issue offered in a public auction. The MTA sold $451 million in notes to the facility in the transaction.12

High borrowing costs, which include the Fed’s “penalty” interest rate above the typical market rate, may limit the MLF to being used as a last resort. However, MLF pricing as of early August was favorable for Illinois and New Jersey, the two states with the lowest credit ratings. New Jersey remains a candidate to use the MLF; the state plans on borrowing $4.5 billion in FY 2021 to be allocated toward the year’s operating budget and allow for replenishing of reserves. Although this has been discussed as a 10-year financing, the state may consider borrowing through the MLF for an initial period and later refinancing in the private market. Hawaii has also expressed interest in using the facility.13

What is the application process?

Interested parties must first submit a notice of interest (NOI) to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York14 and file an application with the bank. If the application is approved, the sale of the notes may be arranged. Issuers should use standard forms of note and the documentation that they typically use when selling securities, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s MLF FAQs. The NOI and other application materials can be found on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s website.15

Conclusion

The MLF has helped to stabilize municipal debt markets by providing a source of emergency financing that could become a critical borrowing tool if state and local budgets are further strained. Although market rates are currently favorable for most municipal borrowers, the economic outlook remains uncertain. Another wave of the pandemic, for example, could lead to a prolonged recession, including a further liquidity squeeze and spikes in municipal bond pricing. Under those conditions, greater demand by municipal borrowers could also impact bond pricing and cause borrowing rates under the MLF to become more attractive.

Further changes to the program’s terms could also make the MLF a more viable financing tool. Extending the term of eligible notes from two to three years has already changed the character of the program from a source of cash flow borrowing to a potential source of deficit financing. If the loan term were extended further or if the issuance window were expanded beyond December 2020, the MLF could provide states and localities with increased flexibility to borrow against higher levels of revenue when the economy begins to recover.

In the meantime, with the length of the economic downturn and federal policy responses highly uncertain, state and local officials may be best served by examining the terms and procedures of this first-of-its-kind Fed program.

Endnotes

- Politico, “Fed to Buy Municipal Debt for First Time, Underscoring Peril Facing Cities,” accessed Aug. 12, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/04/09/fed-to-buy-municipal-debt-178222.

- Ten-year market yields are a much more common benchmark and are available publicly at an array of different credit ratings.

- Twenty states currently have this ability. Six are able to make one additional designation (AL, AK, DE, HI, LA, SC), and 14 are able to designate an additional two (AR, CT, ID, IA, ME, MS, MT, NH, ND, RI, SD, VT, WV, WY). A full list is available on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s FAQs.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Federal Reserve Takes Additional Actions to Provide Up to $2.3 Trillion in Loans to Support the Economy,” news release, April 9, 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200409a.htm.

- A. Klein and C. Busette, “Improving the Equity Impact of the Fed’s Municipal Lending Facility” (Brookings Institution, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-chance-to-improve-the-equity-impact-of-the-feds-municipal-lending-facility/.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “FAQs: Appendix A (PDF)” (2020), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/markets/municipal-liquidity-facility-eligible-issuers.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Municipal Liquidity Facility,” accessed Aug. 14, 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/muni.htm.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “FAQs: Municipal Liquidity Facility,” accessed Aug. 12, 2020, https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/municipal-liquidity-facility/municipal-liquidity-facility-faq.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “New Jersey Considers Tapping New Fed Borrowing Program to Meet Pension Contributions,” accessed Aug. 12, 2020, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/07/15/new-jersey-considers-tapping-new-fed-borrowing-program-to-meet-pension-contributions.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Municipal Liquidity Facility Sample Purchase Rates,” accessed Aug. 12, 2020, https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/municipal-liquidity-facility/municipal-liquidity-facility-sample-rates.

- Reuters, “Illinois to Sell Debt in First Deal With Fed’s Muni Liquidity Facility,” accessed Aug. 12, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-illinois-fed/illinois-to-sell-debt-in-first-deal-with-feds-muni-liquidity-facility-idUSKBN239328.

- Bloomberg, “New York’s MTA Becomes Second to Tap Fed as Banks Demand Higher Yields,” accessed Aug. 18, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-18/ny-mta-becomes-second-to-tap-fed-as-banks-demand-higher-yields.

- K. Dayton, “Gov. Ige Warns That Without More Federal Aid, Hawaii Public Worker Pay Cuts or Furloughs Are Inevitable,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, July 5, 2020, https://www.staradvertiser.com/2020/07/05/hawaii-news/gov-ige-warns-that-without-more-federal-aid-public-worker-pay-cuts-or-furloughs-are-inevitable/.

- According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “the Eligible Issuer will be notified when the NOI package has been approved and may then move forward at the appropriate time with documentation of the transaction.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “FAQs: Municipal Liquidity Facility.”

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Municipal Liquidity Facility Application Materials,” May 18, 2020, https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/municipal-liquidity-facility/municipal-liquidity-facility-application.